By Ed Nuhfer, Guest Editor, California State University (retired)

There are few exercises of thinking more metacognitive than self-assessment. For over twenty years, behavioral scientists accepted that the “Dunning-Kruger effect,” which portrays most people as “unskilled and unaware of it,” correctly described the general nature of human self-assessment. Only people with significant expertise in a topic were capable of self-assessing themselves accurately, while those with the least expertise supposedly held highly overinflated views of their abilities.

The authors of this guest series have engaged in a collaborative effort to understand self-assessment for over a decade. They documented how the “Dunning-Kruger effect,” from its start, rested on specious mathematical arguments. Unlike what the “effect” asserts, most people do not hold overly inflated views of their competence, regardless of their level of expertise. We summarized some of our peer-reviewed work in earlier articles in “Improve with Metacognition (IwM).” These are discoverable by using “Dunning-Kruger effect” in IwM’s search window.

Confirming that people, in general, are capable of self-assessing their competence affirms the validity of self-assessment measures. The measures inform efforts in guiding students to improve their self-assessment accuracy.

This introduction presents commonalities that unify the series’ entries to follow. In the entries, we hotlink the references available as open-source within the blogs’ text and place all other references cited at the end.

Why self-assessment matters

After an educator becomes aware of metacognition’s importance, teaching practice should evolve beyond finding the best pedagogical techniques for teaching content and assessing student learning. The “place beyond” focuses on teaching the student how to develop a personal association with content as a basis for understanding self and exercising higher-order thinking. Capturing the changes in developing content expertise together with self in a written teaching/learning philosophy expedites understanding how to achieve both. Self-assessment could be the most valuable of all the varieties of metacognition that we employ to deepen our understanding.

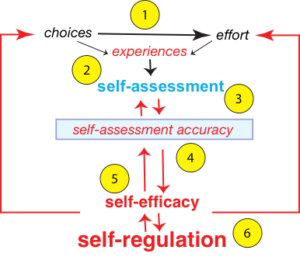

Visualization is conducive to connecting essential themes in this series of blogs that stress becoming better educated through self-assessment. Figure 1 depicts the role and value of self-assessment from birth at the top of the figure to becoming a competent, autonomous lifelong learner by graduation from college at the bottom.

Figure 1. Relationship of self-assessment to developing self-regulation in learning.

Let us walk through this figure, beginning with early life Stage #1 at the top. This stage occurs throughout the K-12 years, when our home, local communities, and schools provide the opportunities for choices and efforts that lead to experiences that prepare us to learn. In studies of Stage 1, John A. Ross made the vital distinction between self-assessment (estimating immediate competence to meet a challenge) and self-efficacy (perceiving one’s personal capacity to acquire competence through future learning). Developing healthy self-efficacy requires considerable practice in self-assessment to develop consistent self-assessment accuracy.

Stage 1 is a time that confers much inequity of privilege. Growing up in a home with a college-educated parent, attending schools that support rich opportunities taught in one’s native language, and living in a community of peers from homes of the well-educated provide choices, opportunities, and experiences relevant to preparing for higher education. Over 17 or 18 years, these relevant self-assessments sum to significant advantages for those living in privilege when they enter college.

However, these early-stage self-assessments occur by chance. The one-directional black arrows through Stage 2 communicate that nearly all the self-assessments are occurring without any intentional feedback from a mentor to deliberately improve self-assessment accuracy. Sadly, this state of non-feedback continues for nearly all students experiencing college-level learning too. Thereby, higher education largely fails to mitigate the inequities of being raised in a privileged environment.

The red two-directional arrows at Stage 3 begin what the guest editor and authors of this series advocate as a very different kind of educating to that commonly practiced in American institutions of education. We believe education could and should provide self-assessments by design, hundreds in each course, all followed by prompt feedback, to utilize the disciplinary content for intentionally improving self-assessment accuracy. Prompt feedback begins to allow the internal calibration needed for improving self-assessment accuracy (Stage #4).

One reason to deliberately incorporate self-assessment practice and feedback is to educate for social justice. Our work indicates that we can enable the healthy self-efficacy needed to succeed in the kinds of thinking and professions that require a college education by strengthening the self-assessment accuracy of students and thus make up for the lack of years of accumulated relevant self-assessments in the backgrounds of those lesser privileged.

By encouraging attention to self-assessment accuracy, we seek to develop students’ felt awareness of surface learning changing toward the higher competence characterized by deep understanding (Stage #5). Awareness of the feeling characteristic when one attains the competence of deep understanding enables better judgment for when one has adequately prepared for a test or produced an assignment of high quality and ready for submission.

People attain Stage #6, self-regulation, when they understand how they learn, can articulate it, and can begin to coach others on how to learn through effort, using available resources, and accurately doing self-assessment. At that stage, a person has not only developed the capacity for lifelong learning, but has developed the capacity to spread good habits of mind by mentoring others. Thus the arrows on each side of Figure 1 lead back to the top and signify both the reflection needed to realize how one’s privileges were relevant to their learning success and cycling that awareness to a younger generation in home, school, and community.

A critical point to recognize is that programs that do not develop students’ self-assessment accuracy are less likely to produce graduates with healthy self-efficacy or the capacity for lifelong learning than programs that do. We should not just be training people to grow in content skills and expertise but also educating them to grow in knowing themselves. The authors of this series have engaged for years in designing and doing such educating.

The common basis of investigations

The aspirations expressed above have a basis in hard data from assessing the science literacy of over 30,000 students and “paired measures” on about 9,000 students with peer-reviewed validated instruments. These paired measures allowed us to compare self-assessed competence ratings on a task and actual performance measures of competence on that same task.

Knowledge surveys serve as the primary tool through which we can give “…self-assessments by design, hundreds in each course all followed by prompt feedback.” Well-designed knowledge surveys develop each concept with detailed challenges that align well with the assessment of actual mastery of the concept. Ratings (measures of self-assessed competence) expressed on knowledge surveys, and scores (measures of demonstrated competence) expressed on tests and assignments are scaled from 0 to 100 percentage points and are directly comparable.

When the difference between the paired measures is zero, there is zero error in self-assessment. When the difference (self-assessed minus demonstrated) is a positive number, the participant tends toward overconfidence. When the difference is negative, the participant has a tendency toward under-confidence.

In our studies that established the validity of self-assessment, our demonstrated competence data in our paired measures came mainly from the validated instrument, the Science Literacy Concept Inventory or “SLCI.” Our self-assessed competence data comes from knowledge surveys and global single-queries tightly aligned with the SLCI. Our team members incorporate self-created knowledge surveys of course content into their higher education courses. Knowledge surveys have proven to be powerful research tools and classroom tools for developing self-assessment accuracy.

Summary overview of this blog series

IwM is one of the few places where the connection between bias and metacognition has directly been addressed (e.g., see a fine entry by Dana Melone). The initial two entries of this series will address metacognitive self-assessment’s relation to the concept of bias.

Later contributions to this series consider privilege and understanding the roles of affect, self-assessment, and metacognition when educating to mitigate the disadvantages of lesser privilege. Other entries will explore the connection between self-assessment, participant use of feedback, mindset, and metacognition’s role in supporting the development of a growth mindset. Near the end of this series, we will address knowledge surveys, the instruments that incorporate the disciplinary content of any college course to improve learning and develop self-assessment accuracy.

We will conclude with a final wrap-up entry of this series to aid readers’ awareness that what students should “think about” when they “think about thinking” ought to provide a map for reaching a deeper understanding of what it means to become educated and to acquire the capacity for lifelong learning.