by Dr. Charles Zola, Associate Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Catholic and Dominican Institute

The values of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) have recently emerged as an area of concern in many areas of contemporary American life. Societal pressure and expectations have motivated many in the business community to examine how these values are promoted in contemporary American business practice. Similarly, accreditors for schools of business now require that these values be reflected in the curriculum and that students demonstrate an awareness of and appreciation for DEI. However, they have not been proscriptive in how this is to be accomplished. I suggest that using case studies can serve this learning outcome and by having students reflect upon their proposed resolutions to DEI-related moral dilemmas arising in business, they develop metacognitive skills which engenders a greater understanding of the implications of DEI in the workplace.

However, they have not been proscriptive in how this is to be accomplished. I suggest that using case studies can serve this learning outcome and by having students reflect upon their proposed resolutions to DEI-related moral dilemmas arising in business, they develop metacognitive skills which engenders a greater understanding of the implications of DEI in the workplace.

Case Studies and Metacognition

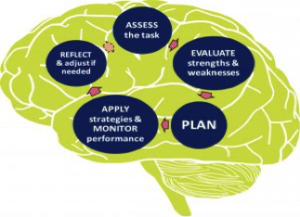

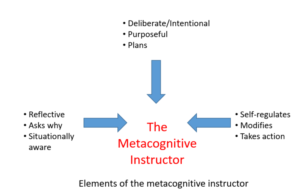

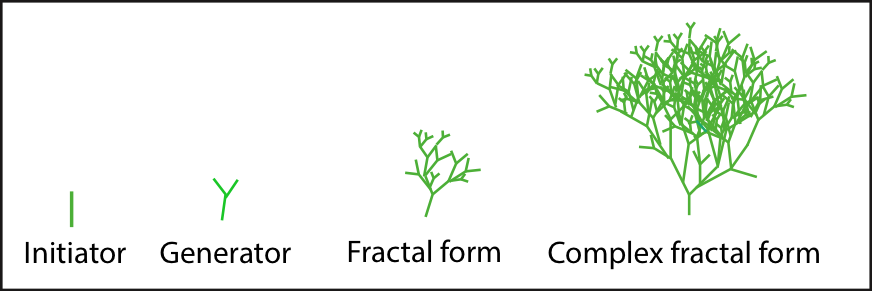

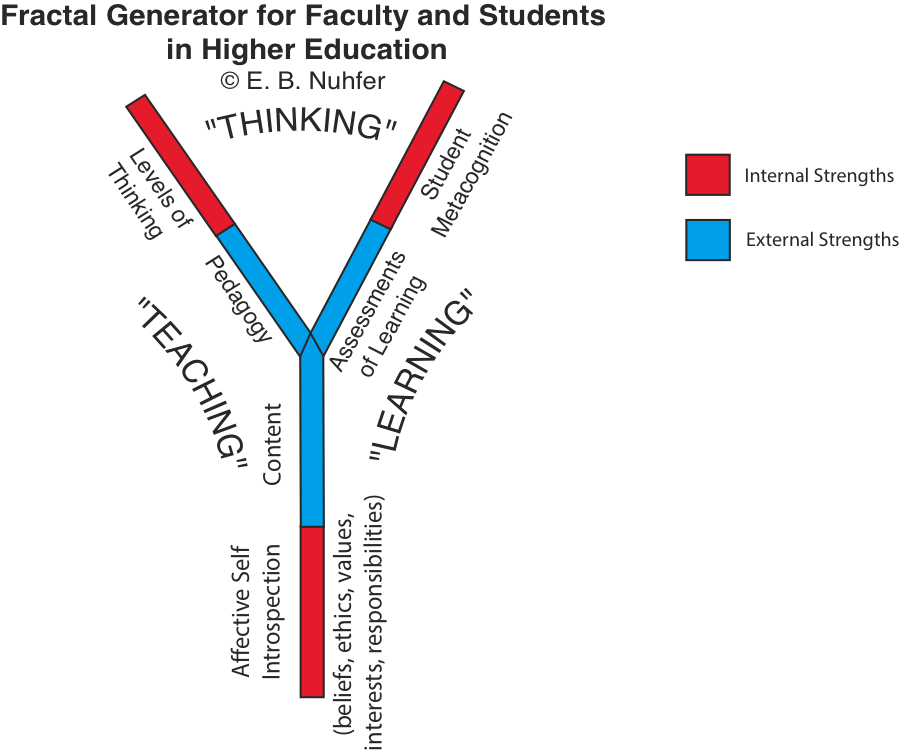

Case studies have long been used as part of business ethics pedagogy. Utilizing case studies promotes understanding of ethical theories that are usually unfamiliar to students and can gradually build student confidence in arguing a moral point of view with the aim of solving a moral dilemma. Beyond this, case study pedagogy can be employed to develop students’ metacognitive capacities. After applying ethical theories to navigate moral dilemmas and justify proposed solutions, students can be prompted to examine why they choose the moral theories that they do and why they apply them in the way they do. Additionally, students can be prompted to resolve the same case study employing a different moral theory, for example, substituting deontological or virtue ethics for a utilitarian approach. They then compare how their proposed resolutions align. In doing so, students not only gain fluency in applied ethical reasoning, but a greater awareness of how their own moral reasoning changes in each iteration. This practice challenges students to be more conscious and reflective about their thinking in terms of application of ethical principles to the same case study and if such application alters the resolution in any way. Inculcating this approach into course pedagogy strengthens students’ metacognitive activity.

If time allows, continued reflection can encourage students to consider the suitability of the application of moral principles among cases, revealing greater similarity and differences not only in the theories themselves but also in procedures and policies that regulate business. In assessing the effectiveness of their proposed solutions, students can be further prompted to re-examine their moral dialectics to ascertain if all aspects of a moral dilemma are adequately addressed and if the moral agents impacted find themselves in a better or worse situation.

One way that this can be encouraged is that for each case study, students could chart the application of each ethical theory where they identify the way/s that moral agents were impacted and how the potential outcomes varied. Each chart can then serve as a metacognitive tool that students use to reflect upon their own thinking processes. If case study analysis is done by teams of smaller groups within a class, then the charts can provide even more information for reflection. A comparison and review of the charts can result in discovering where some essential points were inadequately addressed or not addressed at all, or where potential outcomes were not foreseen. This may result in having students revisit and revise their earlier positions and think about how they reasoned through the moral dilemma. On the other hand, these charts can reveal how their moral reasoning resulted in optimal outcomes, thus affirming the important and practical role that business ethics has for business practice. These varied approaches encourage students to reflect upon their critical thinking and cultivate metacognitive awareness.

Case Studies and DEI

One of the most important topics of a business ethics course that relates to DEI is justice. Classically defined as “giving to each their due,” justice is an essential moral value that regulates how businesses are expected to operate both internally and within the wider community and, thus, is a core value of DEI. Addressing almost every area of business from workplace etiquette to graver considerations such global warming, case studies can be utilized to foster appreciation for the importance of justice. At minimum, businesses act justly in respecting civil law, especially in relation to Civil Rights. These laws seek to eradicate decades of inequality and injustice in terms of business activities related to hiring, promotion, discipline, and discharge of employees and this is closely aligned with the objectives of DEI initiatives. Extending beyond, corporate social responsibility challenges businesses to consider just actions in terms of paternalistic actions within the community that range from philanthropy to efforts to curb and reduce the exploitation of natural resources that often contributes disproportionate harm and inequalities for populations in developing economies.

Case studies drawn from the aforementioned topics can help students understand how justice and the values and goals of DEI are related to business in two distinct ways. First, the case studies themselves can illustrate challenges and opportunities for creating a more diverse, inclusive, and equitable workplace, or how businesses can effectively support those values beyond the workplace through initiatives related to corporate social responsibility.

The other is by reframing the case studies themselves. Changing key characteristics of the moral agents can generate greater sensitivity to some of the moral aims of DEI. Switching the age, sex, gender, race, ethnicity, religion, and socio-economic identity of a moral agent invites students to view the case study and moral dilemma in a different light and from multiple perspectives. For example, would the moral dilemma and proposed solution be the same if the main character was no longer a Hispanic woman but a White woman who was diagnosed with cancer and recently divorced? Are the demands of justice to give to each their due reflected in the case study analysis and subsequent resolution? This reframing can challenge students to reconsider their own moral analysis and proposed resolutions from a more empathetic perspective, hopefully engendering a greater sensitivity to the goals of DEI.

In light of this, students can be encouraged to consider if they would remain committed to what they initially viewed as the moral dilemma, or would this alter the analysis? Similarly, would the proposed resolution of the moral conflict remain the same or would change as well? Further prompting encourages metacognition by challenging students to reflect upon how and why the reframing might have altered their thinking about the moral dimensions of the case study as well as its resolution.

Equally important in raising issues related to justice and DEI is a concern for rectifying societal inequalities of the past. Students can be prompted to review and reflect upon their analysis and proposed resolution of a moral dilemma to discern if it advances the interests of traditionally marginalized groups and affirms a more equitable society. Crafted in this way, case study analysis can raise students’ exploration of the meaning of corporate social responsibility and how it reflects a commitment to social justice.

Beyond this, students could be encouraged to reflect on how their own identities and circumstances may have shaped how they responded to the case study. In what way and to what extent might their own biographies have influenced their impressions about the situation that had been presented and how they reasoned to resolve it? Students can be prompted to examine if their moral reasoning betrayed a bias due to their own circumstances and if not, why not? Such an exercise can be doubly beneficial if students work in teams and share with fellow students their observations, yielding an even wider perspective about how a diversity of viewpoints may impact the resolution of a moral dilemma. Furthermore, doing so also models for students a respect for diversity and inclusion by giving each member of their team “their due” in being able to share their views and having them considered.

Using case studies in the ways described can help to advance one of the essential learning outcomes for schools of business, namely, that future business professionals aspire to ethical conduct in their professional lives and promote it in everyday business practice. Too often, case study pedagogy can remain a mere academic exercise completed unrelated to personal development and cultivating reassessment of personal moral codes. If so, such pedagogical practice is sterile. However, careful attention to case study pedagogy that encourages metacognitive reflection can gradually cultivate habits of moral thinking that translates into moral agency that eventually can be transformative of business practice as it relates to the goals of DEI.