by Steven J. Pearlman, Ph.D. The Critical Thinking Initiative

As the saying goes, you cannot ask a fish about water. Having had no other environmental experience as a counter reference, the fish cannot understand what water is because the fish has never experienced what water isn’t.

Cognition—broadly meaning that the mind is working—is to homo sapiens as water is to fish. So steeped are we in the water of our own cognitive processing that we cannot recognize it. Even though we all possess an extensive list of examples of other people failing to think well, we nevertheless lack an internal reference point for being devoid of thought; every consideration we might make of what it would be like to not-think can only happen through the process of thinking about it.

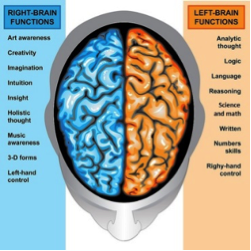

This is the difference between metacognition, which is being intentionally self-aware of what we are doing when we are thinking, and critical thinking, which, loosely speaking, is the capacity to reason through problems and generate ideas. In one sense, we seem to do just fine thinking critically without that metacognitive awareness. We solve problems. We invent the future. We cure diseases. We build communities. But in another all-too-real sense, we struggle, for if we lack the metacognitive acumen to understand what critical thinking is, then we equally lack the capacity to improve our capability to do it and to monitor and evaluate our progress.

The Problem and the Need

Case in point, even though research shows that critical thinking is typically listed among necessary outcomes at educational institutions, “it is not supported and taught systematically in daily instructions” because “teachers are not educated in critical thinking” (Astleitner, 2002). Worse than that, one study of some 30 educators found that not a single one could provide “a clear idea of critical thinking” (Choy & Cheah, 2009). Thus, even though “one would be hard pressed to construct a serious counterargument to the claim that we would like to see students become careful, rigorous thinkers as an outcome of the education we provide them. … By most accounts, we remain far from achieving it” (Kuhn, 1999).

But we do need to achieve that rigorous thinking, because nothing is arguably more important than improving our overall capacity to think. To do so, we must seek to understand the relationship between critical thinking and metacognition, for though interrelated, they’re not the same. In fact, we can think critically without being metacognitive, but we cannot be metacognitive without thinking critically. And that might make metacognition the seminal force of true critical thinking development.

Some Classroom Examples

Consider, for example, asking a student, “What is your thinking about the assigned readings about the Black Lives Matter movement”? Were the student to respond with anything substantive, then we could loosely say the student exercised at least some critical thinking, such as some analysis of the sources and some evaluation of their usefulness. For example, were the student to state that “by referencing statistics on black arrests, source A made a more compelling argument than source B,” then we could rightly say that the student generated some critical thinking. But we cannot say that the student engaged in any metacognitive effort.

But what if the student responded, “Because of its use of statistics on black arrests, Source A changed my thinking about the Black Lives Matter because I was previously unaware of the disparities between white arrest rates and black arrest rates”? Is that metacognitive? Not truly. Even though the student was aware of a change in their own thoughts, they expressed no self-awareness of the internal thinking process that catalyzed that change. There is not necessarily a meaningful distinction between what that student did and someone who says that they had not liked mashed potatoes until they tried these mashed potatoes. They recognized a shift in thought, but not necessarily the underlying mechanism of that shift.

However, if the student responded as follows, we would begin to see metacognition on top of critical thinking: “I realized upon reading Source A that I held a tacit bias about the issue, one that was framed from my own experience being white. I had been working under the assumption that race didn’t matter, and it wasn’t until the article presented the statistics that my thinking was impacted enough for me to become aware of my biases and change my position.” In that sentence, we see the student metacognitively recognizing an aspect of their own thinking process, namely their personal biases and the relationship between those biases and new information. As Mahdvi (2014) said, “Metacognitive thoughts do not spring from a person’s immediate external reality; rather, their source is tied to the person’s own internal mental representations of that reality, which can include what one knows about that internal representation, how it works, and how one feels about it.” And that’s what this example demonstrates: the student’s self-awareness of “internal mental representations of … reality.”

The Value of Metacognition to Critical Thinking

When metacognition is present, all thinking acts are critical because they are by nature under reflection, and scrutiny. While one could interpret a love poem without being metacognitive, one could not be metacognitive about why they interpret a poem a certain way—such as in considering one’s biases about “love” from their personal history—without thinking critically. Since metacognition can only happen when we are monitoring our thinking about something, the metacognition inherently makes the thinking act critical.

Yet, even though metacognition infuses some measure of criticality to thinking, metacognition nevertheless isn’t synonymous with critical thinking. Metacognition alone does not successfully critique existing ideas, analyze the world, develop meaningful questions, produce new solutions, etc. So, we can think without being metacognitive, but if we want to improve our thinking—if we want to understand and enhance the machinations of our mind—then we must seek and attain the metacognitive skills that reveal what our mind is doing and why it is doing it.

Accomplishing that goal requires an introspective humility. It means embracing the premise that our own thinking process is at best always warped, if not often mortally wounded, by our biases, predisposition, and measures of ignorance. It means that we often cannot efficiently solve problems unless we first solve for ourselves, and that’s not easy to do for a bunch of fish who are steeped in the waters cognitive.

References

Astleitner, H. (2002). Teaching Critical Thinking Online. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 29(2), 53-76.

Choy, S.C. & Cheah, P.K. (2009). Teacher perceptions of critical thinking among students and its influence on higher education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 20(2), 198-206.

Kuhn, D. (1999). A developmental model of critical thinking. Educational Researcher, 28(2), 16-25.

Madhavi, M. (2014). An Overview: Metacognition in Education. International Journal of Multidisciplinary and Current Research, 2.