by Gina R. Evers, M.F.A., Director of the Writing Center, Mount Saint Mary College

REFLECTION AS BENCHMARK

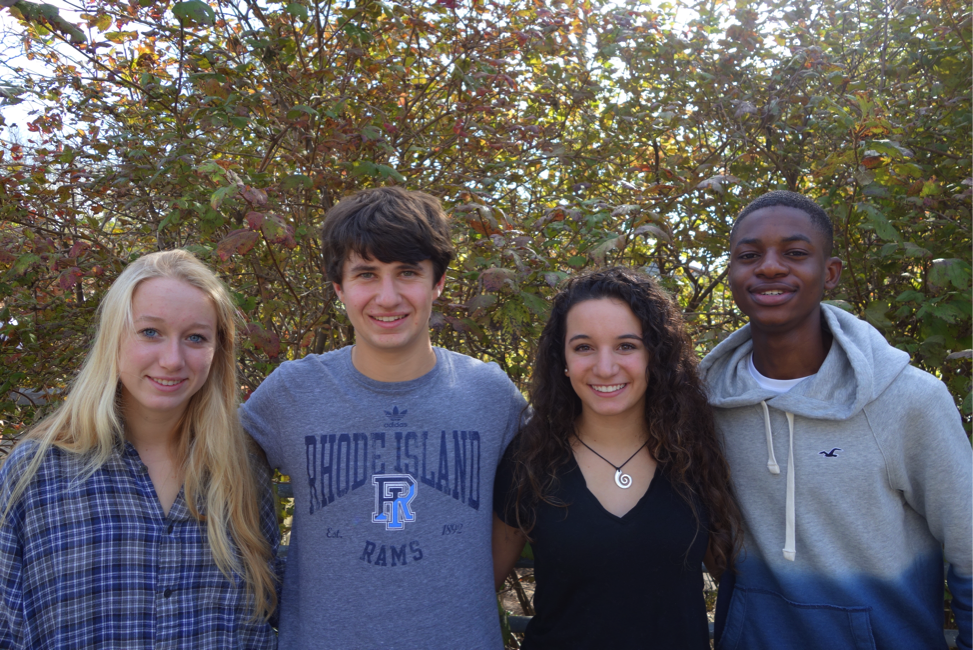

An institution that foregrounds “contemplation” as one of its core Dominican values, Mount Saint Mary College is no stranger to conversations around metacognition. I chime in as the founding director of our on-campus Writing Center. Our mission is to provide supplemental writing instruction, which we do through one-on-one, peer-facilitated consultations. I train and mentor a staff of seven undergraduate writing tutors, who conduct an average of 614 consultations every academic year.

As peer tutors, my team moves fluidly between learning and teaching as they participate in ongoing tutor training while simultaneously advising their writers. This makes training complex, as their roles as tutor-learners shifts to those of tutor-teachers the moment they sit down for an appointment.

So how do I know whether I’ve effectively trained my tutors to not only navigate their dual roles but also to be successful in the one-to-one teaching of writing? My benchmark has become reflection itself. While I certainly equip my team with the necessary grammatical concepts, rhetorical awareness, and writing process theory, I’ve designed this writing instruction within pedagogically reflective structures. Anyone can train in comma usage – no doubt a valuable communication skill – but training in reflection allows the tutor to determine whether and how a lesson on the comma might benefit their writer. When my tutors engage in authentic and honest self-observation, reflection, and ultimately metacognition during our staff meetings, they demonstrate the requisite skill to be effective teachers of writing.

TUTOR-LEARNERS REFLECT ON WRITING CENTER WORK

I asked my tutors for their insights on the role of reflection in tutor training during a recent staff meeting. During our meeting, we discussed assessment scholars Elizabeth Barkley and Claire Major’s comparison of student-learning outcomes to archery. Barkley and Major say a learning goal is an archer seeing their target; a learning objective is an archer aiming for their target, and a learning outcome is an archer hitting their target.

Applying this to the Writing Center, my tutors were quick to extend the analogy. The archer is one of our writers, who comes to us for assistance wielding the bow of writing skills. With our training on how to use the bow, the writer is able to hit their target: a “good” paper. But, as my tutor Leanna astutely noted, if all we do is teach writers to produce “good” papers, once they’re in a new environment they won’t be able to use the bow independently, making the target suddenly elusive and strange.

In his foundational 1984 essay, Stephen North notes that a writing center “represents the marriage of … [writing] as a process … [and] that writing curricula need to be student-centered” (North 49-50). In the Writing Center, it’s the tutors who tailor our writing curricula to every individual writer who walks through our doors. We understand that the writing process is distinct for every individual writer and for every individual writing project they undertake.

North understands this too, and that understanding fuels his dictum that writing centers create “better writers, not better writing (50, emphasis mine). That is to say, because curricula is tailored to each individual, and because that individual’s process varies based on their current project, we have to focus on the individual and their skill set – the archer and their technique in using the bow – in order for them to be able to navigate any future writing project that might be coming their way. In order for the Writing Center to truly support our writers in this, its tutors must be equipped with tools to assess and reflect on what each individual writer needs before teaching them that content.

REFLECTIVE PEDAGOGIES IN WRITING TUTOR TRAINING

For tutor training, my staff and I meet for a two-hour seminar each week. During these meetings, I structure reflection on writing center scholarship, reflection on the tutors’ own writing and writing process, as well as reflection on tutoring skills. The common denominator is clear:

- Writing Center Scholarship. No tutor training program would be complete without covering foundational theories in the one-to-one teaching of writing, and discussions of the readings ask tutors to thoughtfully reflect on their own tutoring practices in light of the scholarship, thereby connecting writing center theory to writing center practice.

- Writing Instruct-shops. A term of my own invention, the writing instruct-shop blends three modes of writing instruction: in-classroom instruction, the writing consultation, and the writing workshop. Using one of the tutor’s pieces of academic writing as the text, I facilitate these instruct-shops to simultaneously practice tutoring skills (borrowing from the writing consultation model), improve tutors’ writing skills (borrowing from the writing workshop model), and gain fluency with the identification and application of components of the writing process, rhetorical concepts, and grammatical conventions (borrowing from the traditional classroom model). Because the tutors’ works are at the center of these conversations, reflection on the duality of their roles as tutor-learners and tutor-teachers emerges.

- Triumphs & Challenges. As a regular agenda item, tutors share the details of one recent writing consultation that left them feeling triumphant as well as one that was particularly challenging. We spend about an hour hearing these reflections and discuss how to revise tutoring techniques for future consultations.

It is pedagogical nomenclature to say that teaching, like writing, is a “reflective practice”; however, I can say with certainty that tutor training is an environment where the rubber meets the road. My tutors concurred: “It’s the reflection that allows us to become better tutors.” Even if you have a challenging session, reflecting on it and asking for help will give you the skills to do something differently next time.

TUTORS AS THE FIRST LINK: A CHAIN OF REFLECTING

The ability to reflect before proceeding is the benchmark of an effectively trained writing tutor. Returning to Barkley and Major, this means that, at least in my work, the target is teaching my students how to reflect before charging through the challenge at hand. Armed with insights from their reflection, the tutors are able to more effectively choose individualized pedagogies to teach their writers. In other words, tutor reflection evolves into tutor metacognition as they adapt skills they’ve learned as tutor-learners and then put them to use as tutor-teachers. My tutor Leanna calls this evolution “a chain of reflecting.” I build reflection into tutor training, my tutors think metacognitively as they transform insights they’ve learned into teaching strategies, and writers then have tools of reflection at their disposal for both their writing projects and the challenges of everyday life. Reflection is the ultimate transferrable skill.

WORKS CITED

Barkley, Elizabeth F. and Claire H. Major. Learning Assessment Techniques: A Handbook for College Faculty, Jossey-Bass, 2016.

North, Stephen M. “The Idea of a Writing Center.” The St. Martin’s Sourcebook for Writing Tutors, Edited by Christina Murphy and Steve Sherwood, Fourth Edition, Bedford St. Martin’s, 2011, pp. 44-58.