by Dr. Kim A. Hosler, Director of Instructional Design, United States Air Force Academy

What struck me…

A few days ago, a colleague and I were talking about what it means to be a deliberate educator. As I was thinking about what that meant, it struck me that to be a deliberate and purposeful educator, one must also be metacognitive about what they are doing and why. Can we say being a deliberate educator is also being a metacognitive educator? This notion gave me pause.

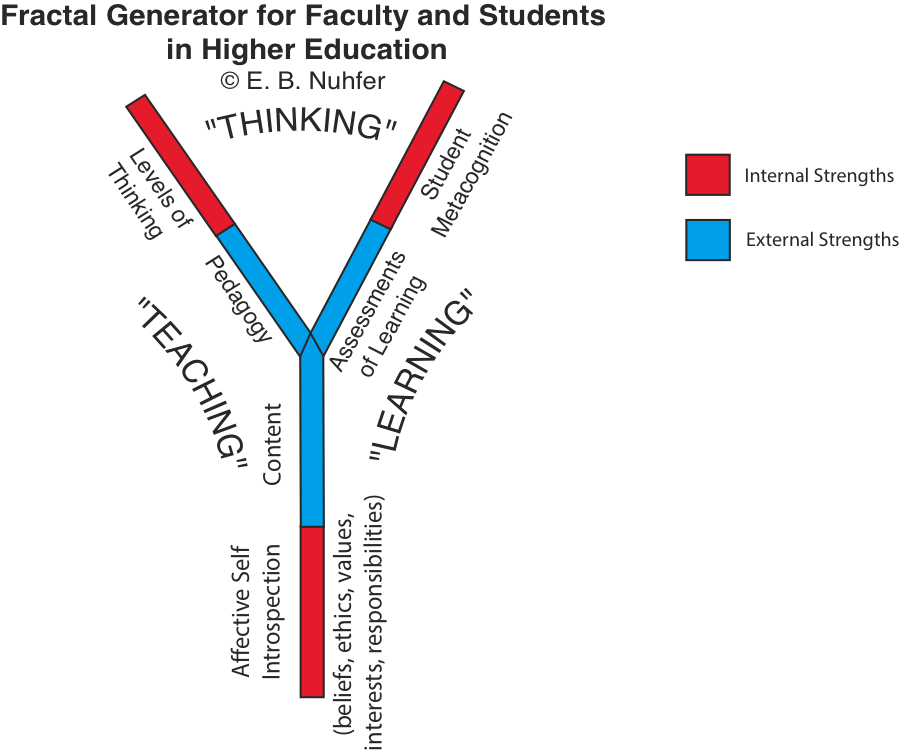

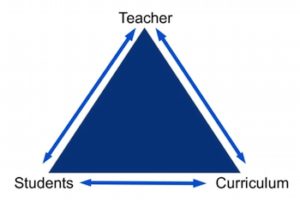

At times we may have a tendency to teach the way we were taught, or in a way that feels right to us. It is possible that an approach that is comfortable for us could lead to effective instruction, but shouldn’t a deliberate educator’s approach to teaching be questioned and explored? Deliberate instructors take time to choose materials, plan course content and learning activities, to respond thoughtfully to learners, all done with intentionality.

Teaching deliberately means that as instructors we are thoughtful, purposeful, and studied about what we do in our classes. It means we put a sustained effort into improving our performance and enriching the learning experiences of our students. According to the McRel Organization (2017), “Being intentional means that teachers know and understand why they are doing what they are doing in the classroom to coach their students to deeper understanding and knowledge.”

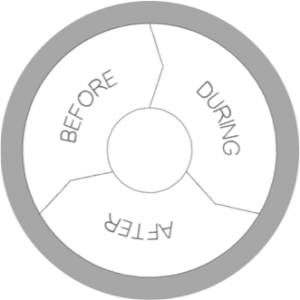

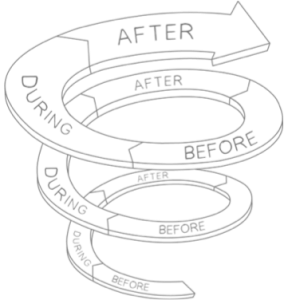

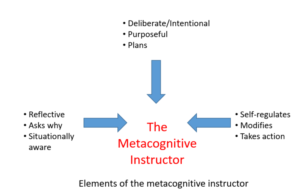

Trede and McEwan (2016) talked about a pedagogy of deliberateness, stating that “beyond praxis, the pedagogy of deliberateness is also about knowing when to and when not to act and to challenge existing ways of doing, saying, relating and knowing” (p. 22). They further explained that a “deliberate professional has to be a thinker and a doer, where the thinking informs the doing and the doing informs the thinking. In that sense, the doing is as much a source for learning as the knowing and thinking” (p. 7). This claim speaks directly to critical elements of metacognition, such as awareness, reflection, cognitive monitoring and improvement. Metacognition is generally summarized as control of one’s cognitive skills, which involves planning, monitoring, and evaluating and then modifying one’s approach as needed to ensure student learning.

Where does metacognition fit in? Answer: Everywhere.

Being intentional and purposeful about my course design and teaching presents only part of the picture. Without thoughtful reflection, are we truly being deliberate and metacognitive? Schaefer (2019) reminded us that a metacognitive instructor “asks why they are proceeding in a particular manner” and then uses that reflective awareness to guide final decisions and actions. This supports the notion that being deliberate necessitates asking reflective, self-regulating questions regarding what we are being deliberate about. Specific questions might include:

- Have I thought through the purpose of the learning activity(ies) I have students completing?

- Can I explain the why of this activity to them?

- Have I taken time to reflect on and note what went well with the learning activity and what I could have done better?

- Have I considered why I am giving students a quiz over the material rather than a short essay? What are the consequences if I don’t give them a quiz or essay?

- In my XYZ lesson, did I relate that content to previous lessons clearly?

- What points of confusion did I observe during class? Why do I think some learners became confused?

- What did I do to make this lesson engaging and interesting? Was it effective?

While I am deliberate and purposeful in my teaching and course design, I find I skimp on the reflection part and avoid asking myself the hard questions. Why, I wonder, am I not taking time to reflect? Do I think I intuitively “get it” and that “it” is correct or the best way? Do I think that being a deliberate educator is enough (no reflection necessary)? Additionally, when I more closely consider what metacognition means, I realize I am missing the self-regulation component, the intentional changes I may need to make after the lesson or course. Reflecting and noting my observations and ideas coupled with deliberate action to improve (self-regulating) will result in my becoming a more effective metacognitive instructor.

Meaningful reflection involves the conscious consideration of one’s beliefs and actions for the purposes of learning and improvement. To reflect, I need to slow down, tolerate the messiness and ambiguity reflection may bring, along with feelings of discomfort, vulnerability, and defensiveness. Without reflection, how do I know what to improve and what needs to be changed to better support student learning?

To help me get started, Porter (2017) offered the following about reflecting.

- Identify important questions and self a reflection process that works for you. Is that talking to others or writing in a journal?

- Set aside time to reflect and stick to it. If you avoid that time, ask yourself why

- Be still with your thoughts

- Consider multiple perspectives

- Start small, set aside 10-minute blocks of time to reflect, especially after an event or class while ideas and observations are fresh

A deliberate educator considers teaching as a purposeful act that can benefit from reflection, analysis, an intentional approach and action. When we are deliberate in our teaching, we know where we are going, how to get there, and the why behind what we are doing. This deliberate process involves taking time for reflection; reflection in planning, for asking the hard questions, and for monitoring our instructional practice. The monitoring of our instructional practice and resulting changes as realized through reflection, moves one from being a deliberate instructor to becoming a metacognitive instructor. Thus, being a deliberate educator is part of being a metacognitive instructor; however, as Scharff (2015) noted, metacognitive instructors also need to make intentional changes based on their reflections and situational awareness.

Please excuse me now, as I want to reflect on what I’ve just written and perhaps make intentional changes.

References

McRel Organization (2017). Intentional teaching inspires intentional learning. Retrieved from https://www.mcrel.org/intentional-teaching-inspires-intentional-learning.

Porter, J. (2017) Why you should make time for self-reflection (even if you hate doing it). Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2017/03/why-you-should-make-time-for-self-reflection-even-if-you-hate-doing-it

Scharff, L. (2015). What Do We Mean by “Metacognitive Instruction”? Retrieved from https://www.improvewithmetacognition.com/what-do-we-mean-by-metacognitive-instruction/

Schaffer, A. (2019) Metacognitive instruction: Suggestions for faculty. Improve with Metacognition. Retrieved from https://www.improvewithmetacognition.com/metacognitive-instruction-suggestions/

Trede, F., & McEwen, C. (2016). Educating the deliberate professional: Preparing for future practice (Vol. 17). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-32958-1.