by Stephen L. Chew, Ph.D. Samford University (slchew@samford.edu)

Critical thinking leads to fewer errors and better outcomes, fueling personal and societal success (Halpern, 1998; Willingham, 2019). The current view is that critical thinking is discipline specific and arises out of subject expertise. For example, a chess expert can think critically about chess, but that analytical skill does not transfer to non-chess situations. The evidence for general critical thinking skills, and our ability to teach them to students, is weak (Willingham, 2019). But these are strange times that challenge that consensus.

The world is currently dealing with COVID-19, a pandemic unprecedented in our lifetime in scope, virulence, and level of contagion. No comprehensive expertise exists about the most effective policies to combat the pandemic. Virologists understand the virus, but not the epidemiology. Epidemiologists understand models of infection, but not public policy. Politicians understand public policy, but not viruses. We are still discovering the properties of COVID-19, fine tuning pandemic models, and trying out new policies. As a result, different countries have responded to the pandemic in different ways. Unfounded beliefs and misinformation have proliferated to fill the void of knowledge, which range from useless to counterproductive and even harmful.

The Relationship between Metacognition and Critical Thinking

If critical thinking can only occur with sufficient expertise, then virtually no one should be able to think critically about the pandemic, yet I believe that critical thinking can play a vital role. In this essay, I argue that metacognition is a crucial element of critical thinking and, because of this, critical thinking is both a general skill and teachable. While critical thinking is most often seen (and studied) in situations where prior knowledge matters, it is in unprecedented situations like this pandemic where more general critical thinking skills emerge and can make a crucial difference in terms of decision making and problems solving.

I’m building on the work of Halpern (1998) who argued that critical thinking is a teachable, general, metacognitive skill. She states, “When people think critically, they are evaluating the outcomes of their thought processes – how good a decision is or how well a problem is solved” (Halpern, 1998, p. 451). Reflection on one’s own thought processes is the very definition of metacognition. Based on Halpern’s work, we can break critical thinking down into five core components:

- Predisposition toward Engaging in Thoughtful Analysis

- Awareness of One’s Own Knowledge, Thought Processes and Biases

- Evaluation of the Quality and Completeness of Evidence

- Evaluation of the Quality of the Reasoning, Decision Making, or Problem Solving

- An Ability to Inhibit Poor and Premature Decision Making

Predisposition toward Engaging in Thoughtful Analysis

Critical thinking involves a personal disposition toward engaging in thoughtful analysis. Strong critical thinkers display this tendency in situations where many people do not see the need, and they engage in more detailed, thorough analysis than many people feel necessary (Willingham, 2019). The variation in the predisposition to think analytically has been on display during the pandemic. Some people simply accept what they hear or read without verifying its validity. In social media, they might pass along information they find interesting or remarkable without distinguishing between valid information, conspiracy, opinion, and propaganda.

The penchant for complex thinking as a habit can be developed and trained. Our educational system should reinforce the value of detailed analysis in preventing costly errors and should give students extensive practice in carrying it out within whatever field the student is studying.

Awareness of One’s Own Knowledge, Thought Processes and Biases

Critical thinking requires insight into the accuracy of what one knows and the extent and importance of what one doesn’t know. It also involves insight into how one’s biases might influence judgment and decision making (West et al., 2008). Metacognition plays a major role in accurate self-awareness.

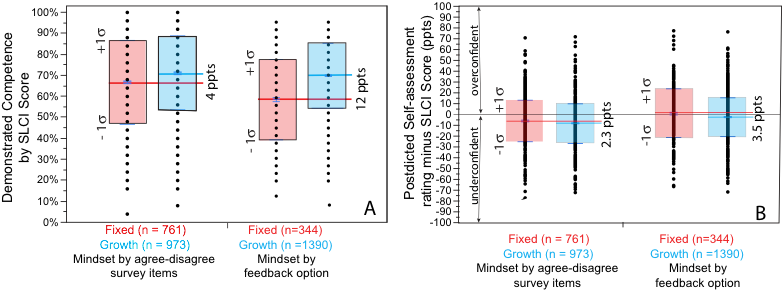

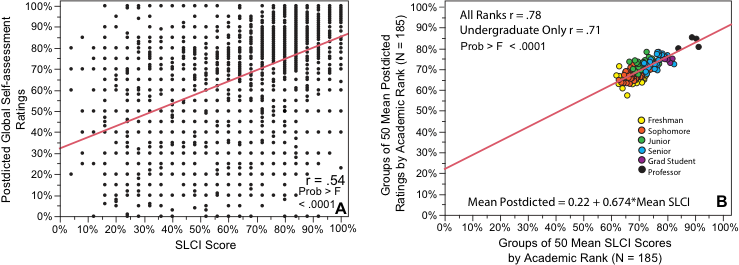

Self-awareness is prone to serious error and bias (Bjork et al., 2013; Metcalfe, 1998). Greater confidence is not the same as greater knowledge. Metacognitive awareness can be poor and misleading (McIntosh et al., 2019). The good news, though, is that poor self-awareness can be overcome through proper experience and feedback (Metcalfe, 1998).

In this pandemic, key critical thinking involves understanding the implications of what we know and continue to discover about COVID-19. One example is the exponential growth rate of COVID-19 infection. Effective responding to the exponential growth involves taking aggressive preventative measures before there is any symptomatic evidence of spread, which, intuitively, seems like an overreaction. Confirmation bias made it easy to accept what people wanted to be true as fact and reject what they did not want to be true as unlikely. Thus, people often ignored warnings about distancing and avoiding large gatherings until the pandemic was well underway.

Recognizing one’s own biases and how to avoid them is a general skill that can be developed through education. Students can be taught to recognize the many biases that can undermine rational, effective thinking (Kahneman, 2011). For example, students can learn to seek out disconfirming evidence to counter confirmation bias (Anglin, 2019). To guard against overconfidence, students can learn to assess their understanding against an objective standard (Chew, 2016).

Evaluation of the Quality and Completeness of Evidence

Critical thinkers understand the importance of evaluating the quality and completeness of their evidence, which involves a metacognitive appraisal. Do I have data of sufficient quality from sufficiently representative samples in order to make valid decisions? What data am I missing that I need? The quality of evidence continues to be of immense concern in the U.S. because of the lack of rapid testing for COVID-19. Critical thinkers understand that data vary in reliability, validity and measurement error. Early in the pandemic, some people believed that COVID-19 was milder than the flu. These people accepted early estimates at face value, without understanding the limitations of the data. What counts for valid data is one aspect of critical thinking that is more discipline specific. Critical thinkers may not be able to evaluate the quality of evidence outside their area of expertise, but they can at least understand that data can vary in quality and it matters greatly for making decisions.

Non-critical thinkers consider data in a biased manner. They may search only for information that supports their beliefs and ignore or discount contradictory data (Schulz-Hardt et al., 2000). Critical thinkers consider all the available data and are aware if there are data they need but do not have. During the pandemic, there were leaders who dismissed the severity of COVID-19 and waited too long to order a quarantine, and there were leaders who wanted to remove the quarantine restrictions despite the data.

Evaluation of the Quality of the Reasoning, Decision Making, or Problem Solving

Critical thinking includes evaluating how well the evidence is used to create a solution or make a decision (e.g. Schwartz et al. 2005). There are general metacognitive questions that people can use to evaluate the quality of any argument. Have all perspectives been considered? Have all alternative explanations been explored? How might a course of action go wrong? Like judgments of evidence, judgments of the strength of an argument is fraught with biases (e.g. Gilovich, 2008; Kraft et al., 2015; Lewandowsky et al., 2012). People more readily accept arguments that agree with their views and are more skeptical of arguments they disagree with, instead of considering the strength of the argument. The pandemic has already spawned dubious studies with selection bias, lack of a control group, or lack careful control, but the “findings” of these studies are embraced by people who want them to be true. Furthermore, people persist in beliefs in the face of clear contradictory evidence (Guenther & Alicke, 2008).

Students should learn about the pitfalls of bias and motivated cognition regardless of their major. Critical thinking involves intellectual humility, an openness to alternative views and a willingness to change beliefs in light of sufficient evidence (Porter, & Schumann, 2018).

An Ability to Inhibit Poor and Premature Decision Making

The last component of a critical thinker is resistance to drawing premature conclusions. Critical thinkers know the limitations of their evidence and keep their reasoning and decision making within its bounds (Noone et al., 2016). They resist tempting but premature conclusions. The inhibitory aspect of critical thinking is probably the least well understood of all the components and deserves more research attention.

Metacognition Supports Critical Thinking

Metacognition, the ability to reflect on one’s own knowledge, plays a crucial role in critical thinking. We see it in the awareness of one’s own knowledge (Component 2), awareness of the quality of evidence and possible biases (Component 3) and the evaluation of the strength of an argument (Component 4). If we wish to teach critical thinking, we need to emphasize these metacognitive skills, both as part of a student’s training in a major and as part of general education. The other two components of critical thinking, the predisposition to engage in critical thinking and the inhibition of premature conclusions, are habits that can be trained.

Critical thinking is hard to do. It takes conscious mental effort and requires overcoming powerful human biases. No one is immune to bad decisions. I assert that critical thinking is a general, teachable skill, especially in situations where decisions have to be made in unprecedented conditions. The pandemic shows that critical decisions often have to be made before sufficient evidence is available. Critical thinking leads to better outcomes by making the best use of available evidence and minimizing error and vulnerability to bias. In these situations, critical thinking is a vital skill, and metacognition plays a major role.

References

Anglin, S. M. (2019). Do beliefs yield to evidence? Examining belief perseverance vs Change in response to congruent empirical findings. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 82, 176–199. https://doi-org.ezproxy.samford.edu/10.1016/j.jesp.2019.02.004

Bjork, R.A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013) Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 417-444. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/4efb/146e5970ac3a23b7c45ffe6c448e74111589.pdf

Chew, S. L. (2016, February). The Importance of Teaching Effective Self-Assessment. Improve with Metacognition Blog. Retrieved from https://www.improvewithmetacognition.com/the-importance-of-teaching-effective-self-assessment/

Gilovich T. (2008). How We Know What Isn’t So: Fallibility of Human Reason in Everyday Life (Reprint edition). Free Press.

Guenther, C. L., & Alicke, M. D. (2008). Self-enhancement and belief perseverance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 44(3), 706-712. doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2007.04.010

Halpern, D. F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains: Disposition, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring. American Psychologist, 53(4), 449-455.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kraft, P. W., Lodge, M., & Taber, C. S. (2015). Why people ‘don’t trust the evidence’: Motivated reasoning and scientific beliefs. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 658(1), 121–133. https://doi-org/10.1177/0002716214554758

Lewandowsky, S., Ecker, U. K. H., Seifert, C. M., Schwarz, N., & Cook, J. (2012). Misinformation and Its Correction: Continued Influence and Successful Debiasing. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(3), 106–131. https://doi-org.ezproxy.samford.edu/10.1177/1529100612451018

Metcalfe, J. (1998). Cognitive optimism: Self-deception or memory-based processing heuristics? Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2(2), 100–110. https://doi-org.ezproxy.samford.edu/10.1207/s15327957pspr0202_3

McIntosh, R. D., Fowler, E. A., Lyu, T., & Della Sala, S. (2019). Wise up: Clarifying the role of metacognition in the Dunning-Kruger effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 148(11), 1882–1897. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000579

Noone, C., Bunting, B., & Hogan, M. J. (2016). Does mindfulness enhance critical thinking? Evidence for the mediating effects of executive functioning in the relationship between mindfulness and critical thinking. Frontiers in Psychology, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.02043

Porter, T., & Schumann K., (2018) Intellectual humility and openness to the opposing view, Self and Identity, 17(2), 139-162, DOI: 10.1080/15298868.2017.1361861

Schulz-Hardt, S., Frey, D., Lüthgens, C., & Moscovici, S. (2000). Biased information search in group decision making. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(4), 655–669. https://doi-org /10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.655

Schwartz, D., Bransford, J., & Sears, D. (2005). Efficiency and innovation in transfer. In J. Mestre (Ed.), Transfer of learning from a modern multidisciplinary perspective (pp. 1-51). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing.

West, R. F., Toplak, M. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (2008). Heuristics and biases as measures of critical thinking: Associations with cognitive ability and thinking dispositions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(4), 930–941. https://doi-org/10.1037/a0012842

Willingham, D. T. (2019). How to Teach Critical Thinking. Education Future Frontiers, New South Wales Department of Education.

If you’ve come across the vast literature on problematic ways of thinking (such as bias, self-deception, and blind spots) and wondered how to avoid such things, then scholars like Van Tongeren are exploring humility as a potential answer.

If you’ve come across the vast literature on problematic ways of thinking (such as bias, self-deception, and blind spots) and wondered how to avoid such things, then scholars like Van Tongeren are exploring humility as a potential answer.