by Dr. Leah Poloskey, Assistant Clinical Professor, Department of Exercise and Rehabilitation Science, Merrimack College, and

by Dr. Sarah Benes, Associate Clinical Professor, Department of Nutrition and Public Health, Merrimack College

(Post #1: Integrating Metacognition into Practice Across Campus, Guest Editor Series Edited by Dr. Sarah Benes)

How it all began . . .

Reflecting on the journey to having a Guest Editor spot with a mini-series of blog posts about metacognition with our colleagues from across campus was a great opportunity to reconnect to the power of community in this work. And it all began with a problem . . .

We had been discussing how challenging it was to engage students in our Health Science classes (Leah teaches in the Exercise and Rehabilitation Department and Sarah teaches in the Nutrition and Public Health Department). We decided to work together to investigate more deeply (rather than just dwelling on the challenge). We applied to host a Teaching Circle, which is an informal structure at Merrimack College that allows faculty and staff to come together around common interests. Teaching Circle facilitators are awarded small stipends for their time and effort in developing and running these opportunities. We believed that the Teaching Circle structure would provide a great opportunity for us to work within existing campus initiatives to enhance collaboration and engagement with faculty and staff across campus.![]()

Our first Teaching Circle was about student engagement. We ended up exploring mindset and the ways that mindset can impact engagement. We conducted a research study where we developed a tool that essentially is a measure of metacognitive states (Mandeville, et al., 2018). With this tool we learned how to assess a student’s self appraisal of their learning, which is a great opportunity to review a student’s intellectual development, mindset and metacognition. Now we had a way to assess these constructs, but what next?

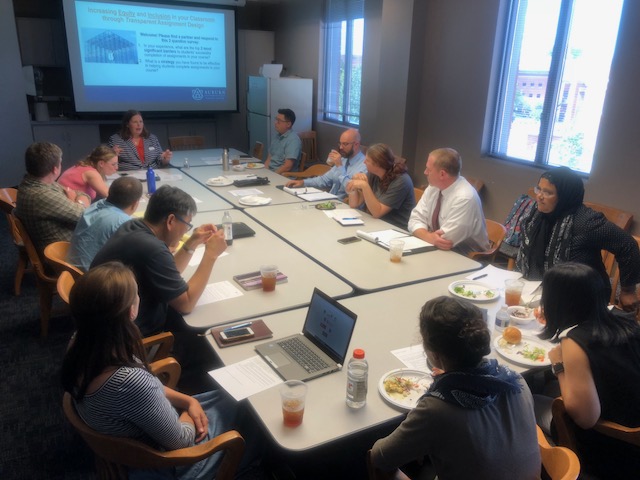

We decided to apply for another Teaching Circle with a focus specifically on Metacognition. Our idea was approved and we were able to engage an even larger group of faculty, staff, and administrators from our academic support staff, to the psychology and business departments and more! Everyone in the group was interested in learning more about ways to support metacognition in our students in our various spaces. And this was the beginning of this blog post series!

What We Learned

Every meeting we had brought together a different group of people depending on schedules and availability. We had core folks who came each time and then a variety of others who came when they were able. Thinking about it now, we remember every meeting being exciting, dynamic, and invigorating.

We didn’t have set agendas and we didn’t have much reading or preparation (unless people asked for items to read). We really just came together to talk and share about our successes and challenges related to supporting students developing their metacognitive skills and to brainstorm ideas to try in our spaces. However, this opportunity for informal community gathering and building was a needed breath of fresh air. We always left energized for the work ahead (and we think the other participants did too!).

In fact, as a result of the Metacognition Teaching Circle, we embarked on a whole new project in which we used the MINDS survey (Mandeville, et al., 2018) at the beginning of the semester and then created “low touch” interventions to support metacognition and growth mindset depending on how students scored on the scale. From this we learned that many students are not familiar with concepts of metacognition and mindfulness, that many actually appreciated the tips and strategies we sent them (and some even used them!), and that students felt that more learning on these topics would be beneficial.

This then lead us to another study, this time examining faculty perceptions of metacognition which we were excited about because our experience suggested that it is likely that folks in certain settings or with certain backgrounds would be more familiar with metacognition and that faculty may not have the understanding or skills to teach metacognition in their courses. For faculty, it is so important to understand the idea of metacognition as it enables students to become flexible and self-directed learners. The teaching and the support of metacognition in the classroom is impactful. It allows students to become aware of their own thinking and to become proficient in choosing appropriate thinking strategies for different learning tasks. Unfortunately, this line of inquiry did not last long due to COVID 19 but we hope to pick this back up this year as we feel it is an important area that could be impactful for faculty and students.

While the research ideas and changes to practice are exciting and were impactful benefits of our Teaching Circles, one of our biggest takeaways was the reminder of the importance of finding others who are also doing the work. Sometimes on our campus, and we suspect it is the case at other institutions as well, we get siloed and often our meetings are with the same folks about the same topics. Being able to facilitate and participate in a cross-campus initiative about a passion topic was an amazing opportunity to meet new people, make new connections, gain different perspectives and create new ideas and strategies to try. We found many people doing great work with students on our campus across so many different departments and schools, and most importantly, found “our people” – people who you can go to when you are stuck, people who you can bounce ideas off of and collaborate with . . . we found our “metacognition people” (some of them at least).

While this was not a “new” idea or “cutting edge”, coming off a year in which we have been separated (in so many ways), we were reminded of the power of connections with others to maintain and sustain ourselves as academics and as humans. We wanted to share that in the guest series by not only showcasing some of the work that our colleagues are doing but also to remind readers to try and find your people . . . whether they are on your campus or off, whether you meet in person or virtual – or only via Tweets on Twitter . . . find the people who can help you maintain, sustain and grow your interest, skills, passion and joy!

We hope you enjoy reading the work of our colleagues and that it helps you on your journey.