by Dr. Marie-Therese C. Sulit, Professor of English and Director of the Honors Program

|

“Literature is no one’s private ground. It is common ground.”–Virginia Woolf “Doce me veritatem”/“Teach Me Truth”—Motto of Mount Saint Mary College |

INTRODUCTION: CONSIDERING DISPUTATIO A FORM OF METACOGNITION

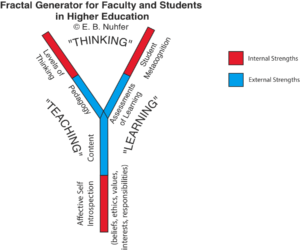

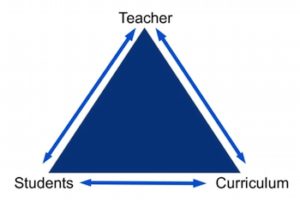

As a multicultural practitioner of literature, I draw upon both a contemplative-informed pedagogy to create safe and brave spaces, especially for young adults. Given the common ground that literature provides, it is important that participants feel safe so they can be brave and share with the class. I connect literacy with literature through the reading process as follows:

- Basic Literacy, or Reading the Lines: discerning the basic plot of a story on your terms (based on our personal experiences and responses) and articulating the “who, what, when, and where” of that story in our speech and prose

- Critical Literacy, or Critically Reading between the Lines: discerning the deeper meaning of the story on its terms and articulating the “how and why” of that story through the background of the story itself and our present historical, literary, and political moment

- Multicultural Literacy, or Reading Critically against the Lines: discerning the gaps and omissions of that story on its and our own terms and articulating ways of filling in these gaps and omissions by posing alternative readings

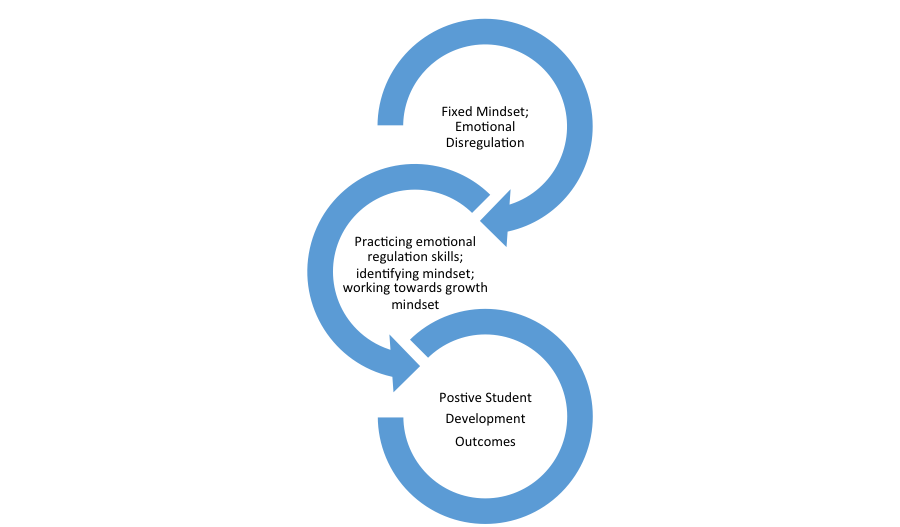

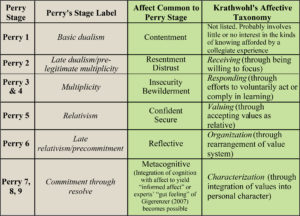

At any stage of the reading process, a student’s engagement with the narrative text can move between emotional reactions and intellectual responses. In an essay, “Reflection Matters: Using Metacognition to Track a Moving Target,” I highlight contemplative pedagogy, which creates a space between one’s emotional reactions and one’s intellectual responses. These reactions and responses inform students’ engagement with literature—may it be a series of spoken or written remarks, difficult and challenging topics, or an emergent potentially controversial set of themes—that, through metacognition, can shift triggers (emotional reactions) into glimmers (intellectual responses) in classroom discussions.

In another essay, “Identity Matters: Creating Brave Spaces through Disputatio and Discernment,” I discuss disputatio, a contemplative practice of rigorous argumentation particular to Dominican colleges and universities, as “[a] method that seeks to resolve difficult questions and controverted issues by finding the truth in each.” The practice of disputatio requires discernment as a means by which multiple and/or disparate perspectives can be brought to light even as it addresses “urgent questions of justice and peace.” At the Mount, pedagogical practices across disciplines are being called upon to explore and investigate so-called “controversial” issues that run the gamut of the “-isms,” e.g. racism and sexism and other forms of oppression. As a teacher of literature, the discernment intrinsic to disputatio, I believe, is a form of metacognition that can be utilized in the classroom in order to gauge students’ connection to a narrative text and peers as well as themselves. There is no better time than the present to engender empathy, the understanding of another perspective, with metacognition to address these opportunities for change in the classroom. Thus, the engenderment of empathy cannot happen without metacognition.

ENGENDERING EMPATHY THROUGH LITERATURE WITH METACOGNITION

The study and analysis of literature not only brings self-examination for all involved as we move through stories, characters, conflicts, and resolutions but also an examination of history, culture and society. In Literature for Young Adults, for example, the relatability of a narrative text opens up the opportunity for young adults to engage in this process of self-examination through the examination of a piece of literature. In providing the common ground to engender empathy, its challenge lies in its inherent predication that another’s experience of pain, even trauma, cannot be our own, and this challenge can happen within a student, among the students in the class, as well as through the characters. In applying these challenges to literature, I draw upon Lou Agosta (2020) who problematizes one’s ability to be open to another, be it a student with another student and/or a student with a character:

- RECEPTIVITY, an emotional contagion, happening through an appropriation of one’s experience;

- INTERPRETATION, as projecting one’s experience onto another, be it a character or a peer can happen;

- RESPONSE, as becoming lost in translation, where gossiping, talking about, or changing the subject can happen;

- UNDERSTANDING, where the labelling or categorizing one’s experience can happen.

With Agosta’s four points, the stages of the reading process are akin to listening: students react and respond accordingly, gauging their reactions and responses. He emphasizes that it is one’s ability to truly listen where empathy can either break down and/or break through. Agosta delineates how empathy works:

- EMPATHIC RECEPTIVITY: a gracious and generous listening

- EMPATHIC INTERPRETATION: the view from “over there”

- EMPATHIC RESPONSIVENESS: the “film” of one’s life—be it a character, a peer, and/or one’s self

- EMPATHIC UNDERSTANDING: a break-through, rather than a break-down, to possibility—be it literary, personal, and/or communal

In this course, the students and I discussed a student-selected contemporary novel, Girl in Pieces (2016) written by Kathleen Glasgow. In this controversial novel, the protagonist is a young woman, Charlie, homeless and a self-harmer, who, through her fraught relationships with family and friends, journeys towards self-development and self-discovery. Charlie served as a surrogate for the students who, to varying degrees, identify and dis-identify with aspects of this protagonist. I find myself most successful in engendering empathy and having the students develop their metacognition through low-stakes writing assignments—e.g. paragraph experiments for practice in writing effective paragraphs and online discussion forums that allow for reflection in responding to topics raised in the classroom. Examples include Charlie’s struggle to not self-harm, her choice in lovers, and her decision to move from place to place. High-stakes writing assignments, like short response papers, allow for deeper reflection on topics initially expressed in the paragraph experiments and online discussion forums. Examples include discussing aspects of a toxic relationship, the role of art in her coping strategies and healing practices, the plight of homeless teenagers. Students are compelled to choose between an approach to their literary studies that emphasizes participation, which can be challenging yet rewarding when students are still learning how they learn best and why they seek to learn. All of this cannot happen without the development of their metacognition through these classroom discussions and writing exercises.

Working through this novel with the students necessitated metacognitive exercises in exploring the creative, emotional, and intellectual that enabled some students to turn triggers into glimmers and other students to engender empathy for the characters and their peers who felt safe and brave enough to share their vulnerabilities. By studying and analyzing Charlie, her choices, her outcome, we became a rich and enriched community.

CONCLUSION

Through literature, I find that diversifying the course content and ensuring an inclusive pedagogy presents the opportunity for instilling students with a sense of curiosity through the process of exploration and discovery—one that comes with their self-development. For students to become life-long learners seeking truth, we bear the responsibility for the cultivation of statements, actions, behaviors, and practices that bespeaks a fully realized human being. We can and must continue to assist students in the development of new ways of being in this world as it is.

WORKS CITED

Agosta, L. (2020, September 6). Retrieved from Empathy Lessons: https://empathyinthecontextofphilosophy.com/2020/09/06/the-trouble-with-the-trouble-with-empathy/

The Dominican Charism in American Higher Education: A Vision in Service of Truth. Dominican University. 2012.

Woolf, Virginia. “Leaning Tower.” The Moment and Other Essays. HMH Books, 2003.