Ed Nuhfer, Retired Professor of Geology and Director of Faculty Development and Director of Educational Assessment, enuhfer@earthlink.net, 208-241-5029

In Part 1, we noted that knowledge surveys query individuals to self-assess their abilities to respond to about one hundred to two hundred challenges forthcoming in a course by rating their present ability to meet each challenge. An example can reveal how the writing of knowledge survey items is similar to the authoring of assessable Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs). A knowledge survey item example is:

I can employ examples to illustrate key differences between the ways of knowing of science and of technology.

In contrast, SLOs are written to be preceded by the phrase: “Students will be able to…,” Further, the knowledge survey items always solicit engaged responses that are observable. Well-written knowledge survey items exhibit two parts: one affective, the other cognitive. The cognitive portion communicates the nature of an observable challenge and the affective component solicits expression of felt confidence in the claim, “I can….” To be meaningful, readers must explicitly understand the nature of the challenges. Broad statements such as: “I understand science” or “I can think logically” are not sufficiently explicit. Each response to a knowledge survey item offers a metacognitive self-assessment expressed as an affective feeling of self-assessed competency specific to the cognitive challenge delivered by the item.

Self-Assessed Competency and Direct Measures of Competency

Three competing hypotheses exist regarding self-assessed competency relationship to actual performance. One asserts that self-assessed competency is nothing more than random “noise” (https://www.koriosbook.com/read-file/using-student-learning-as-a-measure-of-quality-in-hcm-strategists-pdf-3082500/; http://stephenporter.org/surveys/Self%20reported%20learning%20gains%20ResHE%202013.pdf). Two others allow that self-assessment is measurable. When compared with actual performance, one hypothesis maintains that people typically overrate their abilities and generally are “unskilled and unaware of it” (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2702783/). The other, “blind insight” hypothesis, indicates the opposite: a positive relationship exists between confidence and judgment accuracy (http://pss.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/11/11/0956797614553944).

Suitable resolution of the three requires data acquired from paired instruments of known reliability and validity. Both instruments must be highly aligned to collect data that addresses the same learning construct. The Science Literacy Concept Inventory (SLCI), a 25-item test tested on over 17,000 participants, produces data on competency with Cronbach Alpha Reliability .84, and possesses content, construct, criterion, concurrent, and discriminant validity. Participants (N=1154) who took the SLCI also took a knowledge survey (KS-SLCI with Cronbach Alpha Reliability of .93) that produced a self-assessment measure based on the identical 25 SLCI items. The two instruments are reliable and tightly aligned.

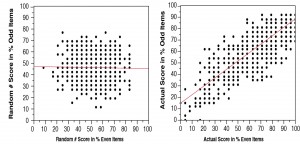

If knowledge surveys register random noise, then data furnished from human subjects will differ little from data generated with random numbers. Figure 1 reveals that data simulated from random numbers 0, 1, and 2 yield zero reliability, but real data consistently show reliability measures greater than R = .9 (Figure 1). Whatever quality(ies) knowledge surveys register is not “random noise.” Each person’s self-assessment score is consistent and characteristic.

Figure 1. Split-halves reliabilities of 25-item KS-SLCI knowledge surveys produced by 1154 random numbers (left) and by 1154 actual respondents (right).

Correlation between the 1154 actual performances on the SLCI and the self-assessed competencies through the KS-SLCI is a highly significant r = 0.62. Of the 1154 participants, 41.1% demonstrated good ability to self-assess their actual abilities to perform within ±10%, 25.1% of participants proved to be under-estimators, and 33.8% were over-estimators.

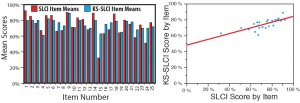

Because each of the 25 SLCI items poses challenges of varying difficulty, we could also test whether participants’ self-assessments gleaned from the knowledge survey did or did not show a relationship to the actual difficulty of items as reflected by how well participants scored on each of them. The collective self-assessments of participants revealed an almost uncanny ability to reflect the actual performance of the group on most of the twenty-five items (Figure 2), thus supporting the “blind insight” hypothesis. Knowledge surveys appear to register meaningful metacognitive measures, and results from reliable, aligned instruments reveal that people do generally understand their degree of competency.

Figure 2. 1154 participants’ average scores on each of 25 SLCI items correspond well (r = 0.76) to their average scores predicted by knowledge survey self-assessments.

Advice in Using Knowledge Surveys to Develop Metacognition

- In developing competency in metadisciplinary ways of knowing, furnish a bank of numerous explicit knowledge survey items that scaffold novices into considering the criteria that experts consider to distinguish a specific way of knowing from other ways of thinking.

- Keep students in constant contact with self-assessing by redirecting them repeatedly to specific blocks of knowledge survey items relevant to tests and other evaluations and engaging them in debriefings that compare their self-assessments with performance.

- Assign students in pairs to do short class presentations that address specific knowledge-survey items while having the class members monitor their evolving feelings of confidence to address the items.

- Use the final minutes of the class period to enlist students in teams in creating alternative knowledge survey items that address the content covered by the day’s lesson.

- Teach students the Bloom Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain (http://orgs.bloomu.edu/tale/documents/Bloomswheelforactivestudentlearning.pdf) so that they can recognize both the level of challenge and the feelings associated with constructing and addressing different levels of challenge.

Conclusion: Why use knowledge surveys?

- Their skillful use offers students many practices in metacognitive self-assessment over the entire course.

- They organize our courses in a way that offers full transparent disclosure.

- They convey our expectation standards to students before a course begins.

- They serve as an interactive study guide.

- They can help instructors enact instructional alignment.

- They might be the most reliable assessment measure we have.