by Steven Fleisher, California State University

Michael Roberts, DePauw University

Michelle Mason, University of Wyoming

Lauren Scharff, U. S. Air Force Academy

Ed Nuhfer, Guest Editor, California State University (retired)

Self-assessment measures and categorizing mindset preference both employ self-reported metacognitive responses that produce noisy data. Interpreting noisy data poses difficulties and generates peer-reviewed papers with conflicting results. Some published peer-review works question the legitimacy and value of self-assessment and mindset.

Yeager and Dweck (2020) communicate frustration when other scholars deprecate mindset and claim it makes no difference under what mindset students pursue education. Indeed, that seems similar to arguing that enjoyment of education and students’ attitudes toward it makes no difference in the quality of their education.

We empathize with that frustration when we recall our own from seeing in class after class that our students were not “unskilled and unaware of it” and reporting those observations while a dominant consensus that “Students can’t self-assess” proliferated. The fallout that followed from our advocacy in our workplaces (mentioned in Part 2 of the entries on privilege) came with opinions that since “the empiricists have spoken,” there was no reason we should study self-assessment further. Nevertheless, we found good reason to do so. Some of our findings might serve as an analogy to demonstrating the value of mindsets despite the criticisms being leveled against them.

How self-assessment research became a study of mindset

In the summer of 2019, the guest editor and the first author of this entry taught two summer workshops on metacognition and learning at CSU Channel Islands to nearly 60 Bridge students about to begin their college experience. We employed a knowledge survey for the weeklong program, and the students also took the paired-measures Science Literacy Concept Inventory (SLCI). Students had the option of furnishing an email address if they wanted a feedback letter. About 20% declined feedback, and their mean score was 14 points lower (significant at the 99.9% confidence level) than those who requested feedback.

In revisiting our national database, we found that every campus revealed a similar significant split in performance. It mattered not whether the institution was open admissions or highly selective; the mean score of the majority who requested feedback (about 75%) was always significantly higher than those who declined feedback. We wondered if the responses served as an unconventional diagnosis of Dweck’s mindset preference.

Conventional mindset diagnosis employs a battery of agree-disagree queries to determine mindset inclination. Co-author Michael Roberts suggested we add a few mindset items on the SLCI, and Steven Fleisher selected three items from Dweck’s survey battery. After a few hundred student participants revealed only a marginal definitive relationship between mindset diagnosed by these items and SLCI scores, Steve increased our items to five.

Who operates in fixed, and who operates in growth mindsets?

The personal act of choosing to receive or avoid feedback to a concept inventory offers a delineator to classify mindset preference that differs from the usual method of doing so through a survey of agree-disagree queries. We compare here the mindset preferences of 1734 undergraduates from ten institutions using (a) feedback choice and (b) the five agree-disagree mindset survey items that are now part of Version 7.1a of the SLCI. That version has been in use for about two years.

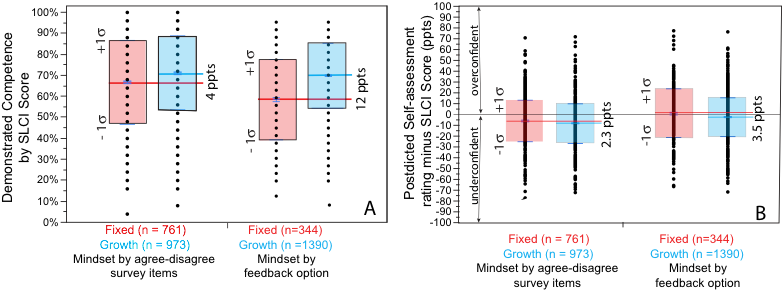

We start by comparing the two groups’ demonstrable competence measured by the SLCI. Both methods of sorting participants into fixed or growth mindset preferences confirmed a highly significant (99.9% confidence) greater cognitive competence in the growth mindset disposition (Figure 1A). As shown in the Figure, feedback choice created two groups of fixed and growth mindsets whose mean SLCI competency scores differed by 12 percentage points (ppts). In contrast, the agree-disagree survey items defined the two groups’ means as separated by only 4 ppts. However, the two methods split the student populace differently, with the feedback choice determining that about 20% of the students operated in the fixed mindset. In contrast, the agree-disagree items approach determined that nearly 50% were operating in that mindset.

We next compare the mean self-assessment accuracy of the two mindsets. In a graph, it is easy to compare mean skills between groups by comparing the scatter shown by one standard deviation (1 Sigma) above and below the means of each group (Figure 1B). The group members’ scatter in overestimating or underestimating their actual scores reveals a group’s developed capacity for self-assessment accuracy. Groups of novices show a larger scatter in their group’s miscalibrations than do groups of those with better self-assessment skills (see Figure 3 of resource at this link).

Figure 1. A. Comparisons of competence (SLCI scores) of 1734 undergraduates between growth mindset participants (color-coded blue) and fixed mindset participants (color-coded red) mindsets as deduced by two methods: (left) agree-disagree survey items and (right) acceptance or opting-out or receiving feedback. “B” displays the measures of demonstrated competence spreads of one standard deviation (1 Sigma) in growth (blue) and fixed mindset (red) groups as deduced by the two methods. The thin black line at 0 marks a perfect self-assessment rating of 0, above which lie overconfident estimates and below which lie underconfident estimates in miscalibrations of self-assessed accuracy. The smaller the standard deviation revealed by the height of the rectangles in 2B, the better the group’s ability to self-assess accurately. Differences shown in A of 4 and 12 ppts and B of 2.3 and 3.5 ppts are differences between means.

On average, students classified as operating in a growth mindset have better-calibrated self-assessment skills (less spread of over- and underconfidence) than those operating in a fixed mindset by either classification method (Figure 1B). However, the difference between fixed and growth was greater and more statistically significant when mindset was classified by feedback choice (99% confidence) rather than by the agree-disagree questions (95% confidence).

Overall, Figure 1 supports Dweck and others advocating for the value of a growth mindset as an asset to learning. We urge contextual awareness by referring readers to Figure 1 of Part 1 of this two-part thematic blog on self-assessment and mindset. We have demonstrated that choosing to receive or decline feedback is a powerful indicator of cognitive competence and at least a moderate indicator of metacognitive self-assessment skills. Still, classifying people into mindset categories by feedback choice addresses only one of the four tendencies of mindset shown in that Figure. Nevertheless, employing a more focused delineator of mindset preference (e.g., choice of feedback) may help to resolve the contradictory findings reported between mindset type and learning achievement.

At this point, we have developed the connections between self-assessment, mindset, and feedback we believe are most valuable to the readers of the IwM blog. Going deeper is primarily of value to those researching mindset. For them, we include an online link to an Appendix to this Part 2 after the References, and the guest editor offers access to SLCI Version 7.1a to researchers who would like to use it in parallel with their investigations.

Takeaways and future direction

Studies of self-assessment and mindset inform one another. The discovery of one’s mindset and gaining self-assessment accuracy require knowing self, and knowing self requires metacognitive reflection. Content learning provides the opportunity for developing the understanding of self by practicing for self-assessment accuracy and acquiring the feeling of knowing while struggling to master the content. Learning content without using it to know self squanders immense opportunities.

The authors of this entry have nearly completed a separate stand-alone article for a follow-up in IwM that focuses on using metacognitive reflection by instructors and students to develop a growth mindset.

References

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487