By Michael J. Serra, Texas Tech University

Part I: Fluency in the Laboratory

Much recent research demonstrates that learners judge their knowledge (e.g., memory or comprehension) to be better when information seems easy to process and worse when information seems difficult to process, even when eventual test performance is not predicted by such experiences. Laboratory-based researchers often argue that the misuse of such experiences as the basis for learners’ self-evaluations can produce metacognitive illusions and lead to inefficient study. In the present post, I review these effects obtained in the laboratory. In the second part of this post, I question whether these outcomes are worth worrying about in everyday, real-life learning situations.

What is Processing Fluency?

Have you ever struggled to hear a low-volume or garbled voicemail message, or struggled to read small or blurry printed text? Did you experience some relief after raising the volume on your phone or putting on your reading glasses and trying again? What if you didn’t have your reading glasses with you at the time? You might still be able to read the small printed text, but it would take more effort and might literally feel more effortful than if you had your glasses on. Would the feeling of effort you experienced while reading without your glasses affect your appraisal of how much you liked or how well you understood what you read?

When we process information, we often have a co-occurring experience of processing fluency: the ease or difficulty we experience while physically processing that information. Note that this experience is technically independent of the innate complexity of the information itself. For example, an intricate and conceptually-confusing physics textbook might be printed in a large and easy to read font (high difficulty, perceptually fluent), while a child might express a simple message to you in a voice that is too low to be easily understood over the noise of a birthday party (low difficulty, perceptually disfluent).

Fluency and Metacognition

Certainly, we know that the innate complexity of learning materials is going to relate to students’ acquisition of new information and eventual performance on tests. Put differently, easy materials will be easy for students to learn and difficult materials will be difficult for students to learn. And it turns out that perceptual disfluency – difficulty processing information – can actually improve memory under some limited conditions (for a detailed examination, see Yue et al., 2013). But how does processing fluency affect students’ metacognitive self-evaluations of their learning?

In the modal laboratory-based examination of metacognition (for a review, see Dunlosky & Metcalfe, 2009), participants study learning materials (these might be simple memory materials or complex reading materials), make explicit metacognitive judgments in which they rate their learning or comprehension for those materials, and then complete a test over what they’ve studied. Researchers can then compare learners’ judgments to their test performance in a variety of ways to determine the accuracy of their self-evaluations (for a review, see Dunlosky & Metcalfe, 2009). As you might know from reading other posts on this website, we usually want learners to accurately judge their learning so they can make efficient decisions on how to allocate their study time or what information to focus on when studying. Any factor that can reduce that accuracy is likely to be problematic for ultimate test performance.

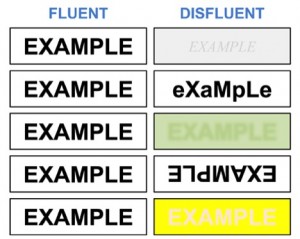

Metacognition researchers have examined how fluency affects participants’ judgments of their learning in the laboratory. The figure in this post includes several examples of ways in which researchers have manipulated the visual perceptual fluency of learning materials (i.e., memory materials or reading materials) to be perceptually disfluent compared to a fluent condition.  These manipulations involving visual processing fluency include presenting learning materials in an easy-to-read versus difficult-to-read typeface either by literally blurring the font (Yue et al., 2013) or by adjusting the colors of the words and background to make them easy versus difficult to read (Werth & Strack, 2003), in an upside-down versus right-side up typeface (Sungkhasettee et al., 2011), and using normal capitalization versus capitalizing every other letter (Mueller et al., 2013). (A conceptually similar manipulation for auditory perceptual fluency might include making the volume high versus low, or the auditory quality clear versus garbled.).

These manipulations involving visual processing fluency include presenting learning materials in an easy-to-read versus difficult-to-read typeface either by literally blurring the font (Yue et al., 2013) or by adjusting the colors of the words and background to make them easy versus difficult to read (Werth & Strack, 2003), in an upside-down versus right-side up typeface (Sungkhasettee et al., 2011), and using normal capitalization versus capitalizing every other letter (Mueller et al., 2013). (A conceptually similar manipulation for auditory perceptual fluency might include making the volume high versus low, or the auditory quality clear versus garbled.).

A wealth of empirical (mostly laboratory-based) research demonstrates that learners typically judge perceptually-fluent learning materials to be better-learned than perceptually-disfluent learning materials, even when learning (i.e., later test performance) is the same for the two sets of materials (e.g., Magreehan et al., 2015; Mueller et al., 2013; Rhodes & Castel, 2008; Susser et al., 2013; Yue et al., 2013). Although there is a current theoretical debate as to why processing fluency affects learners’ metacognitive judgments of their learning (i.e., Do the effects stem from the experience of fluency or from explicit beliefs about fluency?, see Magreehan et al., 2015; Mueller et al., 2013), it is nevertheless clear that manipulations such as those in the figure can affect how much students think they know. In terms of metacognitive accuracy, learners are often misled by feelings of fluency or disfluency that are neither related to their level of learning nor predictive of their future test performance.

As I previously noted, laboratory-based researchers argue that the misuse of such experiences as the basis for learners’ self-evaluations can produce metacognitive illusions and lead to inefficient study. But, this question has yet to receive much empirical scrutiny in more realistic learning situations. I explore the possibility that such effects will also obtain with realistic learning situations in the second part of this post.

References

Dunlosky, J., & Metcalfe, J. (2009). Metacognition. Thousand Oaks, CA US: Sage Publications, Inc.

Magreehan, D. A., Serra, M. J., Schwartz, N. H., & Narciss, S. (2015, advanced online publication). Further boundary conditions for the effects of perceptual disfluency on judgments of learning. Metacognition and Learning.

Mueller, M. L., Tauber, S. K., & Dunlosky, J. (2013). Contributions of beliefs and processing fluency to the effect of relatedness on judgments of learning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20, 378-384.

Rhodes, M. G., & Castel, A. D. (2008). Memory predictions are influenced by perceptual information: evidence for metacognitive illusions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 137, 615-625.

Sungkhasettee, V. W., Friedman, M. C., & Castel, A. D. (2011). Memory and metamemory for inverted words: Illusions of competency and desirable difficulties. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 18, 973-978.

Susser, J. A., Mulligan, N. W., & Besken, M. (2013). The effects of list composition and perceptual fluency on judgments of learning (JOLs). Memory & Cognition, 41, 1000-1011.

Werth, L., & Strack, F. (2003). An inferential approach to the knew-it-all-along phenomenon. Memory, 11, 411-419.

Yue, C. L., Castel, A. D., & Bjork, R. A. (2013). When disfluency is—and is not—a desirable difficulty: The influence of typeface clarity on metacognitive judgments and memory. Memory & Cognition, 41, 229-241.