By Michael J. Serra, Texas Tech University

Part II: Fluency in the Classroom

In the first part of this post, I discussed laboratory-based research demonstrating that learners judge their knowledge (e.g., memory or comprehension) to be better when information seems easy to process and worse when information seems difficult to process, even when eventual test performance is not predicted by such experiences. In this part, I question whether these outcomes are worth worrying about in everyday, real-life learning situations.

Are Fluency Manipulations Realistic?

Researchers who obtain effects of perceptual fluency on learners’ metacognitive self-evaluations in the laboratory suggest that similar effects might also obtain for students in real-life learning and study situations. In such cases, students might study inappropriately or inefficiently (e.g., under-studying when they experience a sense of fluency or over-studying when they experience a sense of disfluency). But to what extent should we be worried that any naturally-occurring differences in processing fluency might affect our students in actual learning situations?

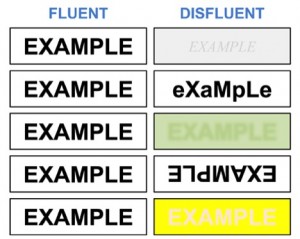

Look at the accompanying figure. This figure presents examples of several ways in which researchers have manipulated visual processing fluency to demonstrate effects on participants’ judgments of their learning. When was the last time you saw a textbook printed in a blurry font, or featuring an upside down passage, or involving a section where pink text was printed on a yellow background?  When you present in-person lectures, do your PowerPoints feature any words typed in aLtErNaTiNg CaSe? (Or, in terms of auditory processing fluency, do you deliver half of the lesson in a low, garbled voice and half in a loud, booming voice?). You would probably – and purposefully – avoid such variations in processing fluency when presenting to or creating learning materials for your students. Yet, even in the laboratory with these exaggerated fluency manipulations, the effects of perceptual fluency on both learning and metacognitive monitoring are often small (i.e., small differences between conditions). Put differently, it takes a lot of effort and requires very specific, controlled conditions to obtain effects of fluency on learning or metacognitive monitoring in the laboratory.

When you present in-person lectures, do your PowerPoints feature any words typed in aLtErNaTiNg CaSe? (Or, in terms of auditory processing fluency, do you deliver half of the lesson in a low, garbled voice and half in a loud, booming voice?). You would probably – and purposefully – avoid such variations in processing fluency when presenting to or creating learning materials for your students. Yet, even in the laboratory with these exaggerated fluency manipulations, the effects of perceptual fluency on both learning and metacognitive monitoring are often small (i.e., small differences between conditions). Put differently, it takes a lot of effort and requires very specific, controlled conditions to obtain effects of fluency on learning or metacognitive monitoring in the laboratory.

Will Fluency Effects Occur in the Classroom?

Careful examination of methods and findings from laboratory-based research suggests that such effects are unlikely to occur in the real-life situations because of how fragile these effects are in the laboratory. For example, processing fluency only seems to affect learners’ metacognitive self-evaluations of their learning when they experience both fluent and disfluent information; experiencing only one level of fluency usually won’t produce such effects. For example, participants only judge information presented in a large, easy-to-read font as better learned than information presented in a small, difficult-to-read font when they experience some of the information in one format and some in the other; when they only experience one format, the formatting does not affect their learning judgments (e.g., Magreehan et al., 2015; Yue et al., 2013). The levels of fluency – and, perhaps more importantly, disfluency – must also be fairly distinguishable from each other to have an effect on learners’ judgments. For example, consider the example formatting in the accompanying figure: learners must notice a clear difference in formatting and in their experience of fluency across the formats for the formatting to affect their judgments. Learners likely must also have limited time to process the disfluent information; if they have enough time to process the disfluent information, the effects on both learning and on metacognitive judgments disappear (cf. Yue et al., 2013; but see Magreehan et al., 2015). Perhaps most important, the effects of fluency on learning judgments are easiest to obtain in the laboratory when the learning materials are low in authenticity or do not have much natural variation in intrinsic difficulty. For example, participants will base their learning judgments on perceptual fluency when all of the items they are asked to learn are of equal difficulty, such as pairs of unrelated words (e.g., “CAT – FORK”, “KETTLE – MOUNTAIN”), but they ignore perceptual fluency once there is a clear difference in difficulty, such as when related word pairs (e.g., “FLAME – FIRE”, “UMBRELLA – RAIN”) are also part of the learning materials (cf. Magreehan et al., 2015).

Consider a real-life example: perhaps you photocopied a magazine article for your students to read, and the image quality of that photocopy was not great (i.e., disfluent processing fluency). We might be concerned that the poor image quality would lead students to incorrectly judge that they have not understood the article, when in fact they had been able to comprehend it quite well (despite the image quality). Given the evidence above, however, this instance of processing fluency might not actually affect your students’ metacognitive judgments of their comprehension. Students in this situation are only being exposed to one level of fluency (i.e., just disfluent formatting), and the level of disfluency might not be that discordant from the norm (i.e., a blurry or dark photocopy might not be that abnormal). Further, students likely have ample time to overcome the disfluency while reading (i.e., assuming the assignment was to read the article as homework at their own pace), and the article likely contains a variety of information besides fluency that students can use for their learning judgments (e.g., students might use their level of background knowledge or familiarity with key terms in the article as more-predictive bases for judging their comprehension). So, despite the fact that the photocopied article might be visually disfluent – or at least might produce some experience of disfluency – it would not seem likely to affect your students’ judgments of their own comprehension.

In summary, at present it seems unlikely that the experience of perceptual processing fluency or disfluency is likely to affect students’ metacognitive self-evaluations of their learning in actual learning or study situations. Teachers and designers of educational materials might of course strive by default to present all information to students clearly and in ways that are perceptually fluent, but it seems premature – and perhaps even unnecessary – for them to worry about rare instances where information is not perceptually fluent, especially if there are counteracting factors such as students having ample time to process the material, there only being one level of fluency, or students having other information upon which to base their judgments of learning.

Going Forward

The question of whether or not laboratory findings related to perceptual fluency will transfer to authentic learning situations certainly requires further empirical scrutiny. At present, however, the claim that highly-contrived effects of perceptual fluency on learners’ metacognitive judgments will also impair the efficacy of study behaviors in more naturalistic situations seems unfounded and unlikely.

Researchers might be wise to abandon the examination of highly-contrived fluency effects in the laboratory and instead examine more realistic variations in fluency in more natural learning situations to see if such conditions actually matter for students. For example, Carpenter and colleagues (Carpenter, et al., in press; Carpenter, et al., 2013) have been examining the effects of a factor they call instructor fluency – the ease or clarity with which information is presented – on learning and judgments of learning. Importantly, this factor is not perceptual fluency, as it does not involve purported variations in perceptual processing. Rather, instructor fluency invokes the sense of clarity that learners experience while processing a lesson. In experiments on this topic, students watched a short video-recorded lesson taught by either a confident and well-organized (“fluent”) instructor or a nervous and seemingly disorganized (“disfluent”) instructor, judged their learning from the video, and then completed a test over the information. Much as in research on perceptual fluency, participants judged that they learned more from the fluent instructor than from the disfluent one, even though test performance did not differ by condition.

These findings related to instructor fluency do not validate those on perceptual fluency. Rather, I would argue that they actually add further nails to the coffin of perceptual fluency. There are bigger problems out there besides perceptual fluency we can be worrying about in order to help our students learn and help them to accurately make metacognitive judgments. Perhaps instructor fluency is one of those problems, and perhaps it isn’t. But it seems that perceptual fluency is not a problem we should be greatly concerned about in realistic learning situations.

References

Carpenter, S. K., Mickes, L., Rahman, S., & Fernandez, C. (in press). The effect of instructor fluency on students’ perceptions of instructors, confidence in learning, and actual learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied.

Carpenter, S. K., Wilford, M. M., Kornell, N., & Mullaney, K. M. (2013). Appearances can be deceiving: instructor fluency increases perceptions of learning without increasing actual learning. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 20, 1350-1356.

Magreehan, D. A., Serra, M. J., Schwartz, N. H., & Narciss, S. (2015, advanced online publication). Further boundary conditions for the effects of perceptual disfluency on judgments of learning. Metacognition and Learning.

Yue, C. L., Castel, A. D., & Bjork, R. A. (2013). When disfluency is—and is not—a desirable difficulty: The influence of typeface clarity on metacognitive judgments and memory. Memory & Cognition, 41, 229-241.