by Rachel Watson, University of Wyoming

Ed Nuhfer, California State University (Retired)

Cinzia Cervato, Iowa State University

Ami Wangeline, Laramie County Community College

Demographics of metacognition and privilege

The Introduction to this series asserted that lives of privilege in the K-12 years confer relevant experiences advantageous to acquire the competence required for lifelong learning and entry into professions that require college degrees. Healthy self-efficacy is necessary to succeed in college. Such self-efficacy comes only after acquiring self-assessment accuracy through practice in using the relevant experiences for attuning the feelings of competence with demonstrable competence. We concur with Tarricone (2011) in her recognition of affect as an essential component of the self-assessment (or awareness) component of metacognition: the “‘feeling of knowing’ that accompanies problem-solving, the ability to distinguish ideas about which we are confident….”

A surprising finding from our paired measures is how closely the mean self-assessments of performance of groups of people track with their actual mean performances. According to the prevailing consensus of psychologists, mean self-assessments of knowledge are supposed to confirm that people, on average, overestimate their demonstrable knowledge. According to a few educators, self-reported knowledge is supposed to be just random noise with no meaningful relationship to demonstrable knowledge. Data published in 2016 and 2017 in Numeracy from two reliable, well-aligned instruments revealed that such is not the case. Our reports in Numeracy shared earlier on this blog (see Figures 2 and 3 at this link) confirm that people, on average, self-assess reasonably well.

In 2019, by employing the paired measures, we found that particular groups of peoples’ average competence varied measurably, and their average self-assessed competence closely tracked their demonstrable competence. In brief, different demographic groups, on average, not only performed differently but also felt differently about their performance, and their feelings were accurate.

Conceptualizing privilege and its consequences

Multiple systems (structural, attitudinal, institutional, economic, racial, cultural, etc.) produce privilege, and all individuals and groups experience privilege and disadvantage in some aspects of their lives. We visualize each system as a hierarchical continuum, along which at one end lie those systematically marginalized/minoritized, and those afforded the most advantages lie at the other. Because people live and work within multiple systems, each person likely operates at different positions along different continuums.

Those favored by privilege are often unaware of their part in maintaining a hierarchy that exerts its toll on those of lesser privilege. As part of our studies of the effects on those with different statuses of privilege, we discovered that instruments that can measure cognitive competence and self-assessments of their competence offer richer assessments than competency scores. They also inform us about how students feel and how accurately they self-assess their competence. Students’ histories of privilege seem to influence how effectively they can initially do the kinds of metacognition conducive to furthering intellectual development when they enter college.

Sometimes a group’s hierarchy results from a lopsided division into some criterion-based majority/minority split. There, advantages, benefits, status, and even acceptance, deference, and respect often become inequitably and systematically conferred by identity on the majority group but not on the underrepresented minority groups.

Being a minority can invite being marked as “inferior,” with an unwarranted majority negative bias toward the minority, presuming the latter have inferior cognitive competence and even lower capacity for feeling than the majority. Perpetual exposure to such bias can influence the minority group to doubt themselves and unjustifiably underestimate their competence and capacity to perform. By employing paired measures, Wirth et al. (2021, p. 152 Figs.6.7 & 6.8) found recently that undergraduate women, who are the less represented binary gender in science, consistently underestimated their actual abilities relative to men (the majority) in science literacy.

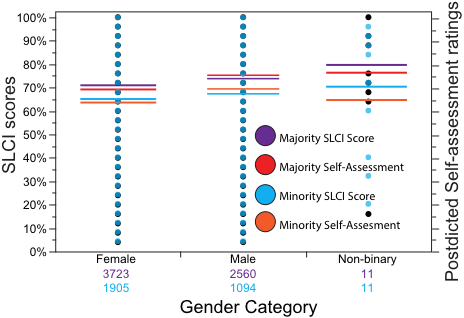

We found that in the majority ethnic group (white Caucasians), both binary genders, on average, significantly outperformed their counterparts in the minority group (all other self-identified ethnicities combined) in both the competence scores of science literacy and the mean self-assessed competency ratings (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Graph of gender performance on measures of self-assessed competence ratings and demonstrated competence scores across ethnic majority/minority categories. This graph represents ten years of data collection of paired measures, but we only recently began to collect non-binary gender data within the last year, so this group is sparsely represented. Horizontal colored lines coded to the colored circles’ legend mark the positions of the means of scores and ratings in percent at the 95% confidence level.

Notably, in Figure 1, the non-binary gender groups, majority or minority, were the strongest academic group of the three gender categories based on SLCI scores. Still, relative to their performance, the non-binary groups felt that they performed less well than they actually did.

On a different SLCI dataset with a survey item on sexual preference rather than gender, researcher Kali Nicholas Moon (2018) found the same degree of diminished self-assessed competence relative to demonstrated competence for the small LGBT group (see Fig. 7 p. 24 of this link). Simply being a minority may predispose a group to doubt their competence, even if they “know their stuff” better than most.

These mean differences in performance shown in Figure 1 are immense. For perspective, pre-post measures in a GE college course or two in science rarely produce more than mean differences of more than a couple of percentage points on the SLCI. In both majority and minority groups, females, on average, underestimated their performance, whereas males overestimated theirs.

If a group receives constant messages that their thinking may be inferior, it is hardly surprising that they internalize feelings of inferiority that are damaging. Our evidence above from several groups verifies such a tendency. We showed that lower feelings of competence parallel significant deficit performance on a test of understanding science, an area relevant to achieving intellectual growth and meeting academic aspirations. Whether this signifies a general tendency of underconfidence in minority groups for meeting their aspirations in other areas remains undetermined.

Perpetuating privilege in higher education

Academe nurtures many hierarchies. Across institutions, “Best Colleges” rating lists perpetuate a myth that institutions that make the list are, in all ways, for all students “better than” those not on the list. Some state institutions actively promote a “flagship reputation,” implying the state’s other schools as “inferior.” Being in a community of peers that reinforces such hierarchical valuing confers damaging messaging of inferiority to those attending the “inferior” institutions, much as an ethnic majority casts negative messages to the minority.

Within institutions, different disciplines are valued differently, and people experience differential privileges across the departments and programs that focus on educating to support different disciplines. The degrees of consequences of stress, alienation, and physical endangerment are minor compared to those experienced by socially marginalized/minoritized groups. Nevertheless, advocating for any change in an established hierarchy in any community is perceived as disruptive by some and can provide consequences of diminished privilege. National communities of academic research often prove no exception.

Takeaways

Hierarchies usually define privilege, and the majority group often supports hierarchies detrimental to the well-being of minority groups. Although test scores are the prevalent measures used to measure learning mastery, paired measures of cognitive competence and self-assessed competence provide additional information about students’ affective feelings about content mastery and their developing capacity for accurate self-assessment. This information helps reveal the inequity across groups and monitors how well students can employ the higher education environment for advancing their understanding of specialty content and understanding of self. Paired measures confirm that groups of varied privilege fare differently in employing that environment for meeting their aspirations.