by Lauren Scharff, PhD, U. S. Air Force Academy,*

Steven Fleisher, PhD, California State University,

Michael Roberts, PhD, DePauw University

It conceptually seems simple… inform students about the positive power of having a growth mindset, and they will shift to having a growth mindset.

If only it were that easy!

In reality, even if we (humans) cognitively know something is “good” for us, we may struggle to change our ways of thinking, behaving, and automatic emotional reactions because those have become habits. However, rather than throw up our hands and give up because it’s challenging, in this blog we will model a growth mindset by offering a new strategy to facilitate the transition to a growth mindset. The strategy involves metacognitive refection, specifically the use of awareness-oriented and self-regulation-oriented questions for both students and instructors.

Mindset Overview

To get us all on the same page, let’s first examine “mindset,” a term coined by Carol Dweck (2006). This concept proposes that individuals internalize ways of thinking about their abilities related to intelligence, learning, and academics (or any other skill). These beliefs become internalized based on years of living and hearing commentary about skills (e.g., She’s a born leader! or, You’re so smart! or, They are natural math wizzes!). These internalized beliefs subsequently affect our responses and performance related to those skills.

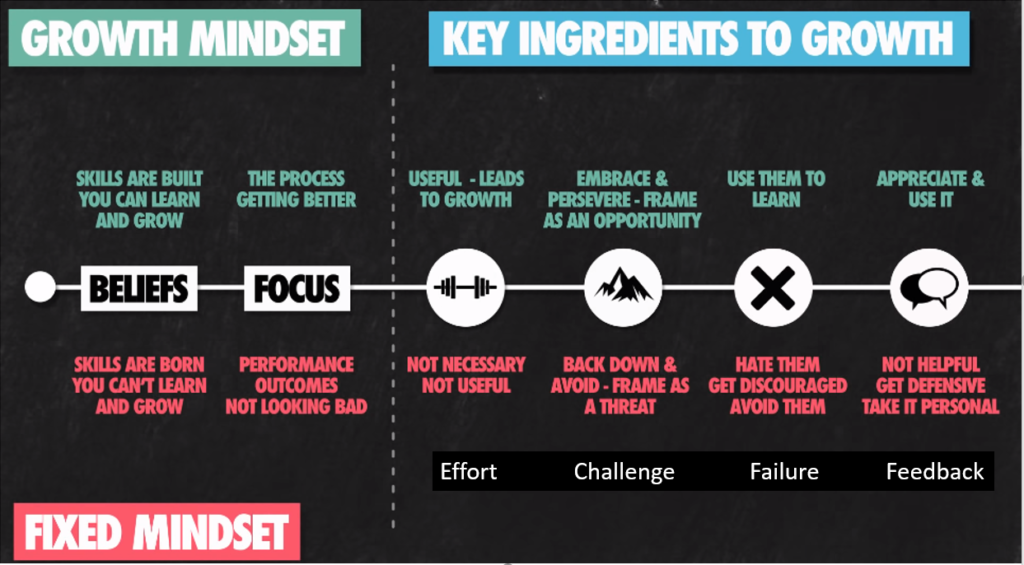

According to Dweck and others, people fall along a continuum (Figure 1) that ranges from having a fixed mindset (“My skills are innate and can’t be developed”) to having a growth mindset (“My skills can be developed”). Depending on a person’s beliefs about a particular skill, they will respond in predictable ways when a skill requires effort, when it seems challenging, when effort affects performance, and when feedback informs performance. The two-part mindset blog posts in Ed Nuhfer’s guest series (Part 1, and Part 2, 2022) provide evidence that the feedback component is especially influential.

Figure 1. Fixed – growth mindset tendencies. (From https://trainugly.com/portfolio/growth-mindset/)

Metacognition to Support Change

As the opening to this blog pointed out, simply explaining the concept of mindset and the benefits of growth mindset to students is not typically enough to lead students to actually adopt a growth mindset. This lack of change is likely even if students say they see the benefits and want to shift to a greater growth mindset. Thus, we need a process to scaffold the change.

We believe that metacognition offers a process by which to do this. Metacognition not only helps us examine our beliefs, but also provides a guide for one’s subsequent behaviors. More specifically, we believe metacognition involves two key processes, 1) awareness, often gleaned through reflection, and 2) self-regulation, during which the person uses that awareness to adjust their behaviors as needed in order to achieve their targeted goal.

Much research (e.g., Isaacson & Fujita, 2006) has already documented the benefits of students being metacognitive about their learning processes. However, we haven’t seen any other work focus on being metacognitive about one’s mindset.

Further, we know that efforts to develop skills are often more successful when they are more narrowly targeted on specific aspects of a broader construct (e.g., Heft & Scharff, 2017). Thus, rather than encouraging students to simply adopt a general “growth mindset,” or be metacognitive about their general mindset for a task, it would be more productive to target how they think about and respond to the specific component aspects of mindset for that task (e.g., challenge, feedback, failure).

Promoting a Growth Mindset Via Metacognition

Below we offer some example metacognitive reflection questions for students and for instructors that focus on awareness and self-regulation related to the feedback component of mindset. For the full set of questions that target all of the mindset components, please go to our full Mindset Metacognition Questions Resource.

We chose to highlight the component of feedback due to Nuhfer et al.’s findings reported in his 2022 guest series. By targeting the specific aspects of mindset, such as feedback, students might more effectively overcome patterns of thinking that keep them stuck in a fixed mindset.

We also include metacognitive reflection questions for instructors because they are instrumental in establishing a classroom environment that either supports or inhibits growth mindset in students. Instructors’ roles are important – recent research has demonstrated that instructor mindset about student learning abilities can impact student motivation, belongingness, engagement, and grades (Muenks, et al., 2020). Yeager, et al. (2021) additionally showed that mindset interventions for students had more impact if the instructors also display growth mindsets. Thus, we suggest that instructors examine their own behaviors and how those behaviors might discourage or encourage a growth mindset in their students.

Student Questions Related to Feedback

- (Self-assessment/awareness) How am I thinking about and responding to feedback that implies I need to make changes or improve?

- (Self-assessment/awareness) How am I interacting with the instructor in response to feedback? (emotional regulation; comfort versus frustration)

- (Self-regulation) How do I plan to respond to feedback I have / will receive?

- (Self-regulation) How might I reasonably seek feedback from peers or the instructor when more is needed?

Instructor Questions Related to Feedback

- (Self-assessment/awareness) Are students using my feedback? Are there aspects of content or tone of feedback that may be interacting with students’ mindsets?

- (Self-assessment/awareness) Am I appropriately focusing my feedback on student performance (e.g., meeting standards) rather than on students themselves (e.g. their dispositions or aptitudes)?

- (Self-regulation) When a student approaches me with a question, what do I signal via my demeanor? Am I demonstrating that engaging with feedback can be a positive experience?

- (Self-regulation) What formative assessments might I develop to provide students feedback about their progress and learn to constructively use that feedback to support their growth?

Take-aways and Future Directions

We believe the interconnections between mindset and metacognition can go beyond the use of metacognition to examine aspects of one’s mindset. Students can be metacognitive about the learning process itself, which can interact with mindset by providing realizations that adapting one’s learning strategies can promote success. The belief that one can try new strategies and become more successful is a hallmark of growth mindset.

We hope that you utilize the questions above for yourself and your students. Given the lack of research in this area, your efforts could make a contribution to the larger understanding of how to effectively promote growth mindset in students. (If you investigate, let us know, and we would welcome a blog post so you could share your results.) At the very least, such efforts might help students overcome patterns of thinking that keep them stuck in a fixed mindset, and it might help them more effectively cope with the inevitable challenges that they will face, both in and beyond the academic realm.

References

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

Heft, I. & Scharff, L. (July 2017). Aligning best practices to develop targeted critical thinking skills and habits. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Vol 17(3), pp. 48-67. http://josotl.indiana.edu/article/view/22600

Isaacson, R.M. & Fujita, F. (2006). Metacognitive knowledge monitoring and self-regulated learning: Academic success and reflections on learning. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Vol 6(1), 39-55. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ854910

Muenks, K., Canning, E. A., LaCosse, J., Green, D. J., Zirkel, S., Garcia, J. A., & Murphy, M. C. (2020). Does my professor think my ability can change? Students’ perceptions of their STEM professors’ mindset beliefs predict their psychological vulnerability, engagement, and performance in class. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 149(11), 2119-2114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/xge0000763

Yeager, D.S., Carroll, J.M., Buontempo, J., Cimpian, A., Woody, S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Murray, J., Mhatre, P., Kersting, N., Hulleman, C., Kudym, M., Murphy, M., Duckworth, A.L., Walton, G.M., & Dweck, C.S.(2022). Teacher mindsets help explain where a growth-mindset intervention does and doesn’t work. Psychological Science, 33(1), 18-32. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/09567976211028984

* The views expressed in this article, book, or presentation are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force Academy, the Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.