by Dr. Ed Nuhfer, California State Universities (retired)

Our previous blog contribution introduced the nature of fractals and explained why the products of intellectual development have fractal qualities. Our brain neurology is fractal, so fractal qualities saturate the entire process of intellectual development. Read the previous blog now, to refresh any needed awareness.

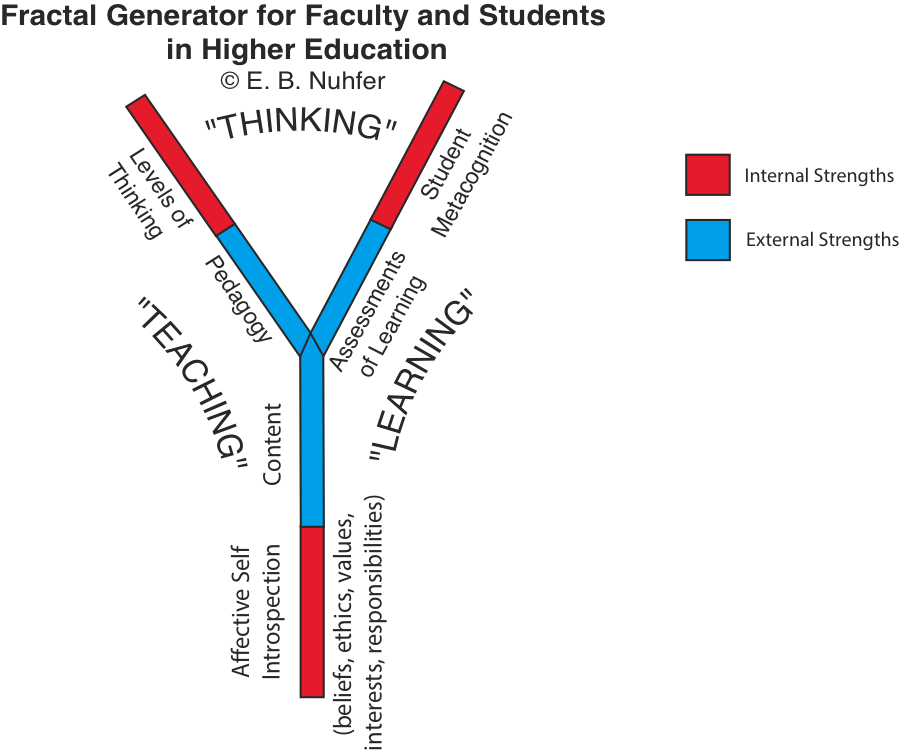

The acts of drafting and using a written philosophy are metacognitive by design. Rare use of philosophies seems symptomatic of undervaluing metacognition. When we operate from a written philosophy, each day offers a practice of metacognition through asking: “Did I practice my philosophy?” That involves considering where we might not have exercised one of the fractal generator’s six components (Figure 1) and then resolve to do so at the next opportunity. Doing so instills the habits of mind needed to do what we intended. Such metacognitive practice is very different from engaging challenges as separately packaged events, without using the “thinking about thinking” needed to understand how our practice was consistent with what we wanted to do. In teaching, we find some of our most significant difficulties appear when we find ourselves doing the opposite of what we most wanted to do. We get into those difficulties by not being aware of the decisions that brought us there.

One possible application of metacognition lies in a large-scale challenge that affects all schools – the annual evaluation of faculty for retention and promotion often reveals chronic problems. How might the standard practices faculty typically experience differ from a practice in which faculty employed written teaching philosophies as a way to address this annual challenge?

WHY Do We Do Annual Review of Faculty?

A metacognitive approach would start with a reflection of the reasons WHY schools go through the prickly annual ritual of evaluating faculty and the outcomes that they hope to attain from doing it. A recent discussion on a faculty development listserv showed that almost no institutions have satisfying answers to “WHY?” For many, an unreflective approach to annual review commonly defaulted to ranking the faculty according to their scores from student ratings forms, sometimes from just one global item on the forms. Asking “WHY?” resulted in the following personal email from an accomplished faculty member: “The main rationale seems in practice often to be simply ‘We have to determine annual merit scores to determine salary increases, and so we have to generate a merit score for teaching (and for research and for service).’”

Given such an annual review process, the faculty will focus on becoming “better teachers” by focusing on raising their student ratings scores, but is that the primary outcome that institutions want? Would we write that “to obtain high student ratings” as a reason that we teach in our teaching philosophies? If we sincerely want effective teaching and student learning, is there a better answer to “WHY?”

Employing Written Philosophies – An Alternate Approach

More specifically, consider which outcome of the following you would choose to expend efforts for yourself or your colleagues: 1) to try to achieve higher student ratings or 2) to improve their mastery of some things labeled in Figure 1 that are known to increase student learning? For example, if a faculty member chose for one year to produce better learning by expanding his knowledge of pedagogy to permit the matching of different kinds of instruction to specific types of content, could that be preferable? Suppose another faculty member discovered that particular stages of adult thinking existed. What if she aspired in the coming year to gain an understanding of this literature, and she focused in the coming year on designing some lessons that helped students to discover the level of thinking they had reached and what their next higher stage might be? Might that be preferable to trying to achieve higher ratings?

Figure 1. We repeat the graphic from Part 1, Figure 2 here. This representation of a philosophy as a fractal generator is somewhat analogous to a stem cell in that it contains all the essential components to produce whatever we need. Metacognition allows us to identify something of value to our current practice. Then for a year, we articulate a philosophy that includes a focus to develop that area.

When we begin to be metacognitive concerning WHY we should want to do annual evaluations and how we should use student input, things should emerge that differ from merely sorting faculty into categories in order to dispense rewards and penalties. Some positive outcomes might be enhancing awareness of how we could design our annual evaluations to help make our institutions more fit places in which to teach and learn, or to provide our graduates with better capacity for life-long learning. In such cases, the nature of annual review changes from an inspection of each faculty member’s popularity with her or his students at the end of their courses into a metacognitive process designed to produce valued outcomes. Management expert Edwards Deming warned particularly about trying to “inspect in” quality at the end of an event or process. Deming’s 14 principles can be condensed into just one concept: “Be metacognitive.” Remain aware of what you most wanted to do when you take any actions to do it.

Changing the Annual Review Format: Embed Metacognition

“Be metacognitive” represents a significant change in most institutional thinking. So, how might we enact this change? One approach would be to design the annual review more like a self-directed contract for practice. Faculty write the philosophies that they intend to practice. A graphic generator like Figure 1 can assist understanding what one now does lots of and too little of. They pick a specific area that they want to do more of and articulate their intent to develop some additional strength in that area. They also articulate WHY they chose this emphasis and what outcome they seek to achieve.

When faculty start their term, they share with their students the emphasis and the outcome through the written syllabus of each class. During the semester, their practice now achieves a metacognitive quality. They regularly reflect on their practice and monitor themselves on whether they are practicing as intended. Their annual review of teaching then becomes a report with parts somewhat like the following.

- Did they practice their stated philosophy?

- How did their students respond?

- How did their practice change, and did that contribute to revisions in their philosophy?

- What is their written contractual plan and philosophy for the coming year?

Weighing the Alternatives

Of the two models of annual evaluations shared above, over-reliance on student ratings for faculty evaluation answers the WHY question with: “We maintain universities so that students can rate the faculty and so that faculty will strive to be rewarded for higher ratings.” Such absurdities arise whenever we practice with no better answers to “WHY?”

As a final thought, consider how an end-of-the-course grade for a student is analogous to annual evaluation for a faculty member. How might teaching students to write their learning philosophies improve their design for learning?