| by Charlie Sweet, Hal Blythe, Rusty Carpenter, Eastern Kentucky University |

Downloadable |

Background

The Provost at Eastern Kentucky University invited Saundra McGuire to speak on metacognition as part of our University’s Provost’s Professional Development Speaker Series. Our unit was tasked with designing related programming both before and after McGuire’s visit. Our aim was to provide a series of effective workshops that prepared the ground for our university’s Quality Enhancement Plan 2.0 on metacognition as a cross-disciplinary tool for cultivating reading skills. The following mind mapping exercise from one of four workshops was taught to over 50 faculty from across campus and the academic ranks. Feedback rated its popularity high and suggested its appropriateness for any level of any discipline with any size class.

Scientific Rationale

The Mind Map, a term invented by Tony Buzan in The Mind Map Book (1993), “is a powerful graphic technique which provides a universal key to unlocking the potential of the brain” (9). For that reason, Buzan’s subtitle is How to Use Radiant Thinking to Maximize Your Brain’s Untapped Potential. A mind map provides a way for organizing ideas either as they emerge or after the fact. Perhaps the mind map’s greatest strength lies in its appeal to the visual sense.

We chose to share mind mapping with our faculty because according to Brain Rules (2008), rule number ten is “Vision trumps all other senses” (221). For proof, the author, John Medina, cites a key fact: “If information is presented orally, people remember about 10%, tested 72 hours after exposure. That figure goes up to 65% if you add a picture” (234). Because of its visual nature, mind mapping provides a valuable metacognitive tool.

How Mind Mapping Supports Metacognition

Silver (2013) focuses on reflection in general and in particular “the moment of meta in metacognition—that is the moment of standing above or apart from oneself, so to speak, in order to turn one’s attention back upon one’s own mental work” (1). Mind mapping allows thinkers a visual-verbal way to delineate that moment of reflection and in capturing that moment to preserve its structure. Because analysis is one of Bloom’s higher-order learning skills, mind mapping leads to deep thinking, which makes self-regulation easier.

Method

Essentially, a mind map begins with what Gerry Nosich in Learning to Think Things Through (2009) calls a fundamental and powerful concept, “one that can be used to explain or think out a huge body of questions, problems, information, and situations” (105). To create a mind map, place the fundamental and powerful concept (FPC) you wish to explore in the center of a piece of paper and circle it. If at all possible, do something with color or the actual lettering in order to make the FPC even more visual. For instance, if you were to map the major strategies involved in metacognition, metacognition is the FPC, and you might choose to write it as such:

M E T A

Cognition

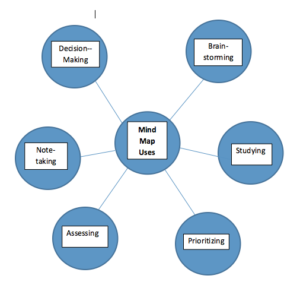

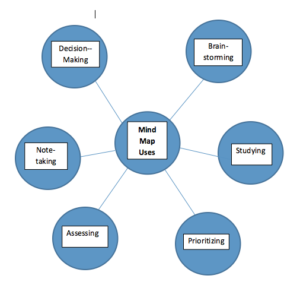

Increasing the visual effect of the FPC are lines that run to additional circled concepts that support the FPC. These Sputnik-like appendages are what Buzan calls basic ordering ideas, “key concepts within which a host of other concepts can be organized” (p. 84). For example, if you were working with our metacognition example, your lines might radiate out to a host of also-circled metacognitive strategies, such as retrieving, reflection, exam wrappers, growth mindset, and the EIAG process of Event selection-Identification of what happened-Analysis-Generalization of how the present forms future practice (for a fuller explanation see our It Works for Me, Metacognitively, pp. 33-34). And if you wanted to go one step further, you might radiate lines from, for instance, retrieving, to actual retrieving strategies (e.g., flashcards, interleaving, self-quizzing).

Uses for Mind Maps

Mind mapping has many uses for both students and faculty:

- Notetaking: mind mapping provides an alternative form of notetaking whether for students or professors participating in committee meetings. It can be done before a class session by the professor, during the session by the student, or afterwards as a way of checking whether the fundamental and powerful concept(s) was taught or understood.

- Studying: instead of rereading notes taken, a method destined for failure, try reorganizing them into a mind map or two. Mind mapping not only offers the visual alternative here, but provides retrieval practice, another metacognitive technique.

- Assessing: instead of giving a traditional quiz at the start of class or five-minute paper at the end, ask students to produce a mind map of concept X covered in class. This alternative experiment will demonstrate to students a different approach and place another tool in their metacognitive toolbox.

- Prioritizing: when items are placed in a mind map, something has to occupy center stage. Lesser items are contained in the radii.

Outcomes

Mind maps are easy, deceptively simplistic, fun, and produce a deep learning experience. Don’t believe it? Stop reading now, take out a piece of paper, and mind map what you just read. We’re willing to bet that if you do so, the result will provide a reflection moment.

References

Buzan, T. (1993). The mind map book: How to use radiant thinking to maximize your brain’s untapped potential. New York: Plume Penguin.

McGuire, S. Y., & McGuire, S. (2015). Teach students how to learn: Strategies you can incorporate into any course to improve student metacognition, study skills, and motivation. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Medina, J. (2008). Brain rules. Seattle: Pear Press.

Nosich, J. (2009). Learning to think things through. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Silver, N. (2013). Reflective pedagogies and the metacognitive turn in college teaching.

In M. Kaplan, N. Silver, D. Lavaque-Manty, & D. Meizlish (Eds.), Using reflection and metacognition to improve student learning (pp. 1-17). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Sweet, C., Blythe, H., & Carpenter, R. (2016). It Works for Me, Metacognitively. Stillwater, OK: New Forums.

Appendix: How to Use Word to Create a Mind Map

- Click Insert.

- Click Shapes and select Circle.

- Click on desired position, and the circle will appear.

- Click on Draw Textbox.

- Type desired words in textbox (you may have to enlarge the textbox to accommodate words).

- Drag textbox into center of circle.

- Repeat as desired.

- To connect circles, click Insert Shapes and then Select Line.

- Drag Line between circles.