by Jessica Santangelo and Ilona Pierce, Hofstra University

We may be an unlikely pair at first glance – an actor and a biologist. We met after Jess gave a talk about the role of metacognition in supporting student learning in biology. Ilona realized during the talk that, though unfamiliar with the term metacognition, what she does with theatre students is inherently metacognitive. This has led to rich conversations about metacognition, the role of metacognition in teaching, and the overlap between the arts and STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and mathematics).

Here we offer a condensed version of one of our conversations in which we explored the overlap between metacognition in the arts and STEM (STEAM).

Ilona: In actor training, (or voice/speech training, which is my specialty) self-reflection is the core part of an actor’s growth. After a technique is introduced and application begins, we start to identify each student’s obstacles. In voice work, we examine different ways we tighten our voices and bodies then explore pathways to address the tension. As tension is released, I’ll typically ask, “What do you notice? How are things different than they were when we began?” This is what hooked me in at your lecture….you worked with the students, uncovering their shortcomings (their version of TENSION) and you watched their test scores go up. It was a great thing to see, but I sat there thinking, “doesn’t every teacher do that?”

Jess: In my experience, most STEM courses do not intentionally or explicitly support students reflecting on themselves, their performance, or their learning strategies. I’m not entirely sure why that is. It may be a function of how we (college-level STEM educators) were “brought up,” that many of us never had formal training in pedagogy, and/or that many STEM educators don’t feel they have time within the course to support students in this way.

When you contacted me after the lecture, I had an “aha!” moment in which I thought “Woah! She does this every day as an inherent part of what she does with her students. It’s not something special, it’s just what everyone does because it’s essential to the students’ learning and to their ability to grow as actors.” Though you hadn’t been aware of the term “metacognition” before the talk, what you are having your students do IS metacognitive.

Ilona: Of course, the students have to be taught to notice, and prodded into verbalizing their observations. In the beginning, when I ask, “What do you notice?” I’m typically met with silence. They don’t know what they notice. I have to guide them: “How has your breathing changed? Are you standing differently? What emotions arose?” As the course goes on, I’ll ask for deeper observations like, “How does your thinking/behavior during class help you/hinder you? What patterns are arising?” It’s not unusual to hear things like, “I realized I talk fast so that people don’t have the chance to interrupt me,” or “If I speak loudly, I’m afraid people will think I’m rude.”

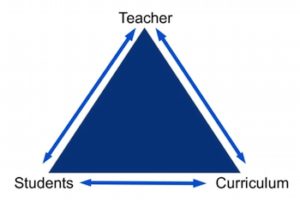

Jess: I think that highlights a difference in the approach that educators within our respective fields take to our interactions with students. Your class is entirely focused on the student, the student’s experience, and having the student reflect on their experience so they can adjust/adapt as necessary.

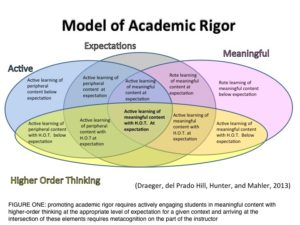

In contrast, for many years, the design of STEM courses and our interactions with students focused on the conveyance of content and concepts to students. Some STEM classes are becoming more focused on having the students DO something with content/concepts in the classroom (i.e., active learning and flipped classrooms), but that hasn’t always been the case. Nor does having an active learning or flipped classroom mean that the course intentionally or explicitly supports student metacognitive development.

Ilona: Principles and content are an important part my coursework as well, but most of it is folded into the application of the skills they’re learning. The environment helps to support this kind of teaching. My students are hungry young artists and the class size is 16 – 18 max. This allows me to begin by “teaching” to the group at large, and then transition to doing one-on-one coaching.

When you work with your students, do you work individually or in small groups?

Jess: I am pretty constrained in terms of what I can do in the classroom as I generally have 44-66 students/section (and faculty at other institutions are even more constrained with 100+ students/section!). However, even with my class size, I generally try to minimize whole-group lecture by having students work in small groups in the classroom, prompting them to discuss how they came to a conclusion and to make their learning visible to each other. One-on-one “coaching” generally occurs during office hours.

I’m really drawn to the word “coaching” here. I feel like you literally coach students – that you work with them, meeting them wherever they are in that moment, and help them gain awareness and skills to get to some endpoint. Does that accurately capture how you view yourself and your role? How does that play out in terms of your approach to your classes and to your interactions with students?

Ilona: I think it’s “teacher” first and then I transition to “coach”. But I also use one-on-one coaching to teach the entire class. For example, one student gets up to share a monologue or a poem. Afterwards, I ask a question, maybe a couple: ”What did you notice about your breathing? Your body? Your emotions?” If the student has difficulty answering, I’ll guide them to what I noticed: “Did you notice… i.e. your hands were in fists the whole time?” I might turn to the class and say, “Did you guys notice his hands?” The class typically will notice things the performer doesn’t. I’ll ask the class, “As an audience member, how did his clenched hands make you feel (emotionally, physically)? Did you want him to let them go, or did it help the piece?” So the coaching bounces from the individual to the group, asking for self-reflection from everyone.

Jess: It sounds like we do something similar in that, as I prompt one student in a small group to explain how they arrived at a conclusion, I’m using that as an opportunity to model a thought process for the rest of the group. Modeling the thought process alone isn’t necessarily metacognitive, but I take it a step farther by asking students to articulate how the thought process influenced their ability to come to an accurate conclusion and then asking them to apply a similar process in other contexts. I’m essentially coaching them towards using thought process that is inquisitive, logical, and evidence-based – I’m coaching them to think like a scientist.

When I reflect on my title: professor/teacher/instructor/educator versus coach, I’m struck that the title brings up very different ideas for me about my role in the classroom – it shifts my perspective. When I think of professor/teacher/instructor/educator, I think of someone who is delivering content. When I think of a coach, I think of someone standing on the sidelines, observing an athlete perform, asking the athlete to do various exercises/activities/drills to improve various aspects of their performance. You seem to fit squarely in the “coach” category to me – you are watching the students perform, asking students to reflect on that performance, and then doing exercises to improve performance via the release of tension.

Ilona: I definitely do both. Coaching to me implies individualized teaching that is structured in a way to foster independence. Eventually, a coach may just ask questions or offers reminders. It’s the last stop before students leave to handle things on their own. Like parenting, right? We start with “hands on”, and over time we teach our children to become more and more independent, until they don’t need us anymore.

Jess: I wonder how often STEM educators think of themselves at coaches? How does viewing oneself as a coach alter what one does in the classroom? Is there a balance to be struck between “teaching” and “coaching”? How much overlap exists between those approaches?

In thinking about myself, I can wear both hats depending on the circumstance. I can “teach” content and “coach” to help students become aware of their level of content mastery. When I think of myself as a teacher, I feel responsible for getting students to the right answer. When I think of myself as a coach, I feel more responsible for helping them be aware of what they know/don’t know and supporting their use of strategies to help them be successful. Isn’t that the point of an athletic coach? To help an athlete be aware of their bodies and their abilities and then to push an athlete to do and achieve more within their sport? The academic analogy then would be to push a student to be aware of what they know or don’t know and to effectively utilize strategies to increase their knowledge and understanding. The goal is to get students doing this on their own, without guidance from an instructor.

The other piece to this is how the students respond and use the metacognitive skills we are trying to help them develop. I wonder: Are your students, who are being encouraged to develop strong metacognitive skills in their theatre classes, naturally transferring those skills and using them in other disciplines (like in their bio class!)? If not, and if they were prompted to do so, would they be more likely to do so (and do so successfully) than non-theatre students who haven’t been getting that strong metacognitive practice?

Ilona: One would hope so. My guess is that when they get into non-acting classes, they revert to the student skills they depended on in high school. Although, I often get “metacognitive success stories” after summer break. Students will report that during their lifeguard or food-service gig, they realized their growing skills of self-awareness helped them to do everything from using their voices differently to giving them greater insight into their own behavior. If they can make connections like this during a summer job, perhaps they can apply these skills in their bio class.

many teachers would choose “go with your gut instinct”, otherwise known as the First Instinct Fallacy (Kruger, Wirtz, & Miller, 2005). In this well-known article by Kruger and colleagues, they found (in 4 separate experiments) that when students change their answers, they typically change from incorrect to correct answers, they underestimate the number of changes from incorrect to correct answers, and overestimate the number of changes from incorrect to correct. Ironically, but not surprisingly, because students like to “go-with-their-gut”, they also tend to be very hesitant to switch their answers and regret doing so, even though they get the correct answer. However, what Kruger and colleagues did not investigate was the role that metacognition may play in the First Instinct Fallacy.

many teachers would choose “go with your gut instinct”, otherwise known as the First Instinct Fallacy (Kruger, Wirtz, & Miller, 2005). In this well-known article by Kruger and colleagues, they found (in 4 separate experiments) that when students change their answers, they typically change from incorrect to correct answers, they underestimate the number of changes from incorrect to correct answers, and overestimate the number of changes from incorrect to correct. Ironically, but not surprisingly, because students like to “go-with-their-gut”, they also tend to be very hesitant to switch their answers and regret doing so, even though they get the correct answer. However, what Kruger and colleagues did not investigate was the role that metacognition may play in the First Instinct Fallacy. (whether they knew it or guessed the answer), and to indicate whether or not they changed their initial answer. Consistent with Kruger et al. (2005) results, Couchman and colleagues found that students more often change their initial response from incorrect to correct answers than the reverse. What was interesting is that when students thought they knew the answer and didn’t change their answer, they were significantly more likely to get the answer correct (indicating higher metacognition). When students guessed, and didn’t change their answer, they were significantly more likely to get the answer incorrect (indicating low metacognition). Moreover, when compared to questions students thought they knew, when students revised guessed questions, they choose the correct answer significantly more often than when they didn’t change their answer. In other words, students did better on questions when they guessed and changed their answer to when they thought they knew the answer and changed their answer. These results suggested that students were using the metacognitive construct of cognitive monitoring to deliberately choose when to revise their answers or when to stick with their gut on a question-by-question basis.

(whether they knew it or guessed the answer), and to indicate whether or not they changed their initial answer. Consistent with Kruger et al. (2005) results, Couchman and colleagues found that students more often change their initial response from incorrect to correct answers than the reverse. What was interesting is that when students thought they knew the answer and didn’t change their answer, they were significantly more likely to get the answer correct (indicating higher metacognition). When students guessed, and didn’t change their answer, they were significantly more likely to get the answer incorrect (indicating low metacognition). Moreover, when compared to questions students thought they knew, when students revised guessed questions, they choose the correct answer significantly more often than when they didn’t change their answer. In other words, students did better on questions when they guessed and changed their answer to when they thought they knew the answer and changed their answer. These results suggested that students were using the metacognitive construct of cognitive monitoring to deliberately choose when to revise their answers or when to stick with their gut on a question-by-question basis. indicate a judgment of confidence for each question on the test (either use a categorical judgment such as low vs. medium vs. high confidence or use a 0-100 confidence scale). Then, if students are low in their confidence, instructors should encourage them to change or revise their answer. However, if student confidence is high, they should consider not changing or revising their answer. Interestingly enough, this must be done in real-time, because if students make this confidence judgment at post-assessment (i.e., at a later time), they tend to be overconfident and inaccurate in their confidence ratings. Thus, the answer to the First Instinct Fallacy is—like most things—complicated. However, don’t just respond with a simple “it depends”—even though you are correct in this advice. Go the step further and explain and demonstrate how to improve adaptive control and cognitive monitoring.

indicate a judgment of confidence for each question on the test (either use a categorical judgment such as low vs. medium vs. high confidence or use a 0-100 confidence scale). Then, if students are low in their confidence, instructors should encourage them to change or revise their answer. However, if student confidence is high, they should consider not changing or revising their answer. Interestingly enough, this must be done in real-time, because if students make this confidence judgment at post-assessment (i.e., at a later time), they tend to be overconfident and inaccurate in their confidence ratings. Thus, the answer to the First Instinct Fallacy is—like most things—complicated. However, don’t just respond with a simple “it depends”—even though you are correct in this advice. Go the step further and explain and demonstrate how to improve adaptive control and cognitive monitoring.