by Gina Burkart, Ed.D., Learning Specialist, Clarke University

The 2021 Academic year brought new challenges to education, as teaching and learning quickly moved online. Those who had never taught online received crash courses and hoped for the best. Students found themselves learning either remotely from home or alone in dorm rooms through web conferencing. While online learning offered convenience, the remote and distant nature of the learning often left students and professors feeling isolated from each other. As a professor, I noticed students to be less engaged in discussions and interactions with each other. In online forums, other professors and colleagues complained of the same. As the semester progressed, students’ motivation seemed to plummet.

As the Learning Specialist on campus, I reach out regarding the Academic Concerns raised for students on campus. Academic Concerns are raised by professors through an electronic alert system when students struggle academically or stop attending class. The concerns come to my email and I reach out to the students and cc the students’ advisors and athletic coaches. During the 2020-21 academic year, I observed a large increase in concerns sent for students not submitting assignments, not attending class, and not participating in discussions. Lack of student motivation seemed to underlie many of these trends. As I read articles and discussion boards across the nation, I saw the problem was epidemic.

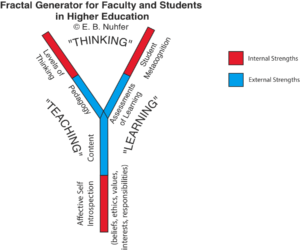

This blog post describes how I addressed this lack of motivation and engagement by incorporating metacognitive conversations into my work with students for whom Academic Concerns had been raised, and by incorporating similar metacognitive exercises into my Learning Strategies course. The majority of the students in the Learning Strategies course are on academic probation, so they often start with very low motivation. Some had been dismissed but allowed back in to the university on a last chance.

Engaging Struggling Students through Empathy and Metacognitive Conversations

I have been working with college students for over twenty years, and it continues to amaze me how much they crave to be heard. As previously mentioned, the past year, this need for connection and communication was epidemic—so much so that my calendar was full of meetings with students (every 30 minutes) throughout the entire Fall semester. Students wanted to meet and talk—and they often scheduled regular weekly meetings. The other anomaly was they kept the meetings—even on Fridays! These meetings became pivotal to rebuilding their motivation. And, it all began with empathy.

Discussions of the effects of technology on relationships and the importance of empathy in education are not new. Social Psychologist Sherry Turkle has been researching this connection between technology and human relationships since the 1970’s. Most recently she has written about how increased time with technology has negatively impacted our ability to interact with each other. In Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age, Turkle (2015) said “Fully present to one another, we learn to listen. It is where we develop the capacity for empathy. . . . And conversation advances self-reflection, the conversations with ourselves . . . . (p. 3).

In meeting with the students, even though it was online, I worked to remove the barrier of technology and make the meeting human by conversing with them as though we were sitting together casually in my office. I asked students how they were doing, the names of their cats and dogs, about their family members, and I told them a little bit about what was going on with me. THEN I asked about what was going on with their courses. I empathized with them a bit and then we moved on to problem solve in a metacognitive conversation. A metacognitive conversation guides students in reflecting on and monitoring their cognitive processes, progress, and performance to build self-efficacy. For example, after empathizing with a student, I asked:

- What is causing you to not turn in the assignments?

- What might you do about that? How could I help?

- What is interfering with you attending class? What might make a difference? How could I help?

- How did you study for the test? What is one change you could make?

- What if you tried this?

- How might I help you?

I found it helpful to ask open-ended questions and let them talk as much as possible. Students really like to be heard. Many are seldom listened to and crave an audience. They also benefit from hearing themselves. Also, I benefit from hearing them talk—as I begin to pick up on themes I can say things like “I heard you say _____ a couple of times. This leads me to believe you tend to _____________.” They often respond with “exactly!” I then offer them some suggestions based on research and show them resources to try.

Together, we form a simple goal for them to implement and accomplish in a week and check on in the next week. I model it and practice it with them. Also, I connect the struggling student with a student Academic Coach who is trained by me. They can continue to work on the goal and engage in further metacognitive conversations. This type of follow up and academic mentoring between students fosters motivation and metacognition, as evidenced by increased class participation, improved GPAs, and attendance.

As Turkle (2021) shared in her latest book The Empathy Diaries “ . . . only shared vulnerability and human empathy allow us to truly understand one another” (xix). Once the students felt heard and understood, they were willing to work with me to solve their problems. In knowing someone else invested in them, they were willing to invest in themselves.

Infusing Metacognition in a Learning Strategies Course

I needed to revisit this lesson in my own teaching in the Spring when I also noticed a lack of student motivation in my own courses—even with the new infused strategies. And, it wasn’t that the students were confused. Over and over, they told me that the course was simple and easy to use and made sense. They demonstrated the ability to find materials and understanding of how to access materials. Yet, assignments were not being turned in. As motivation dwindled, important curriculum would not be studied and articles would go unread. Deadlines continued to be missed. The online chats I had set up with peer mentors for participation were not being attended. Engagement was dismal and grades were plummeting. So, although I already had incorporated some metacognitive strategies into the course, at midterm I attempted to infuse what was working with one/one meetings with students.

This effort began with midterm conferences. I always have had students evaluate themselves on the goals they set at the beginning of the semester and go over how they are progressing in the course. Students have always been amazingly honest. When I did this during the spring 2021 semester, they openly and apologetically shared they were not motivated and were not looking at the curriculum or submitting work. So, we focused on what was causing the lack of motivation.

Since the course curriculum (College Study Strategies) had all the resources they needed to solve the motivation problems, we revisited the resources in the course that they had missed—such as articles, videos, and power points on motivation, procrastination, time management, and so on. We read some together and set goals. I also reopened the deadlines so they could revisit the curriculum they needed and complete the discussions (now that they had purpose and motivation). They admitted they had known where the resources were and how to access them—they said they just had not had motivation to do it. But, after we had discussed how the resources applied to their situation and would help, and set specific goals, they began to appreciate a reason and need to access the materials.

To reinforce the goals set and encourage usage and follow through of the materials, I allowed extra credit to make up missed online chats related to the missed curriculum if students scheduled meetings to discuss the curriculum with an Academic Coach. The Academic Coach reported the meetings to me. The results of behavior changes after midterm conferences were significant. For example, at midterm there were 15 Fs in the course out of 28 students. When I submitted final grades, there were only 5 Fs. One F had changed to an A and 2 Fs had become Bs.

This experience led me to again appreciate the power of metacognitive conversations with students. Specifically, it reinforced how empathy can motivate students—even through technology and in a pandemic.

References

Turkle, S. (2021). The empathy diaries. New York: Penguin Press.

Turkle, S. (2015). Reclaiming conversations: The power of talking in a digital age. New York: Penguin Press.

Image from: https://www.connecttocommunicate.com/