by John Draeger, SUNY Buffalo State

I have developed a variety of metacognitive exercises over the years, but I never thought I’d develop a card game. The nerd in me likes the fact that a metacognitive card game now exists. While I want to tell you about how the game came about, I am also writing because the story includes an important metacognitive moment.

Promoting metacognition in traditional educational settings

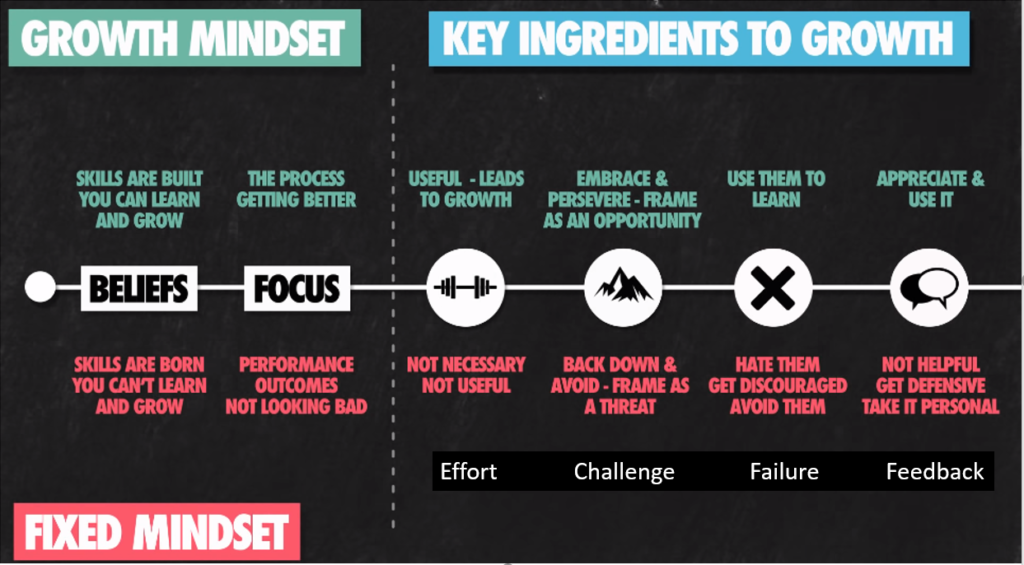

Most of my metacognitive exercises have been designed for classroom settings where students are asked to become aware of their various learning processes (such as reading, writing, ethical reasoning) and their experience with their process (such as feeling stuck). If students can become aware of what’s working and what’s not, then they can better recognize where they need to make adjustments and find ways to improve.

As a small part of a National Science Foundation (NSF) funded project, I developed metacognition exercises to support students doing course-based undergraduate research (EvaluateUR-CURE).[1] These efforts yielded a collection of twelve exercises that provide students with opportunities to build metacognitive habits as well as a guidebook for instructors (Metacognitive exercises and Guides). These exercises provide students with opportunities to practice metacognition in ways that support the broad elements of EvaluateUR-CURE (E-CURE for short).

Each metacognitive exercise helps students attend to various elements of their research process (such as reading for research, developing good research questions, managing projects, building resilience, and effectively communicating results). Once aware of their process, students can then decide whether they need to make adjustments to their process or perhaps seek out additional resources. The guidebook provides instructors and mentors with quick ways to integrate student metacognition into the conversations that they are already having in the classroom. While not specifically designed to support the version of the EvaluateUR method for students conducting independent research with a faculty mentor, the exercises developed for E-CURE can be very useful in a variety of settings.

Time for an adjustment?

My design challenge changed dramatically when working on another NSF funded project aimed at developing a variant of the method – called Evaluate-Compete – for students participating in engineering design competitions. The goal was to help students develop and become aware of academic and workforce skills through their involvement in these competitions. The NSF project initially focused on the MATE ROV competition where high school and college students build underwater vehicles to simulate solving various real-world marine challenges. Teams work all year on their vehicles and then compete in a series of regional competitions in hopes of qualifying for the World Championships. As with the course-based research projects, I was tasked with designing exercises to support metacognitive growth.

I quickly encountered a problem. Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs) are fun. I had the good fortune of attending the MATE ROV world championships in 2021 and 2022. It is easy to see why teams spend countless hours designing, testing, and tweaking their ROVs. It’s fun. Therein lies both secret to student engagement and flaw in my plan to use worksheets to promote metacognition.

Before, during, and after the competitions, the focus is on the vehicles, vehicle systems, and vehicle performance. The students creating these vehicles are learning all sort of things (and that’s ultimately the point), but it surely seems like it is all about the vehicles. In the previous NSF project, metacognitive exercises encouraged students to pause long enough to consider where they might need to make adjustments in their process and how they might take those lessons into the next learning context. Hands-on research was the secret to student engagement, but the classroom or the structured mentoring setting was the secret to students completing and discussing the metacognitive exercises.

Unlike those settings, students building ROVs were not always tied to formal classes and often work as part of a club, student organization, or a group of friends seeing if they were up to the challenge. The goal in designing the exercise was to promote skill building and reflection on their learning process as they design vehicles and solve problems. But why would anyone do metacognitive exercises when there is no grade attached, especially if you could be focusing on an ROV instead?

Why Cards?

It was time for me to take my own metacognitive medicine. Metacognition refers to an intentional awareness about a process. My process for designing metacognitive questions was going well enough and it worked in other settings, but my initial attempts to pitch worksheets to eager young engineers fell flat and it was quickly obvious that the strategy was never going to work.

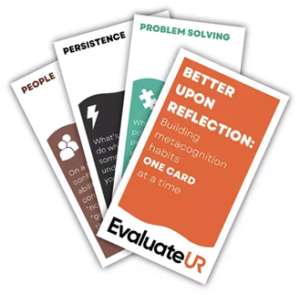

Metacognition reminds us to make adjustments when a particular strategy isn’t working. My strategy was doomed. I needed an adjustment. If I could get students to pause and reflect on their process, then the prompts had a chance of helping them build better habits. But how to get them to pause long enough to engage the prompts? I needed a fun way to engage students in reflection about their learning that could be done anywhere, anytime, with any number of people. Because regular practice is important to habit formation, I further hoped that something fun could improve frequency of use and aid habit formation. I shifted strategies and designed a metacognitive card game.

Want to play?

The resulting metacognitive cards can be used at any time, in any order, or in any combination. They can be played by individuals or by a team. Each contains a series of “fun” prompts organized in three categories – problem-solving, persistence, and working with people. Ways to play can be found within each deck, including on planes, trains, at team meetings, and pizza parties. For example, the game can be played individually or in a group. When teams play, individuals can answer from the point of view of someone else in the group, pass a card to someone else for them to respond, or shift perspective by answering from the point of view of someone outside the group. Early feedback on the cards is positive and feedback collection is ongoing. I’ll have more to say future posts. For now, if YOU would like to play the Better upon reflection: building metacognitive habits ONE card at a time card game, you can request a deck or print out your own deck. And if you play, I’d love to hear how it goes.

[1] Special thanks to the EvaluateUR-Method team – Jill Singer, Sean Fox, Daniel Weiler, Jill Zande, Emma Binder, Maureen Kahn, and Bridget Zimmerman.