Dr. Sarah Benes, Associate Clinical Professor, Department of Nutrition and Public Health, Merrimack College

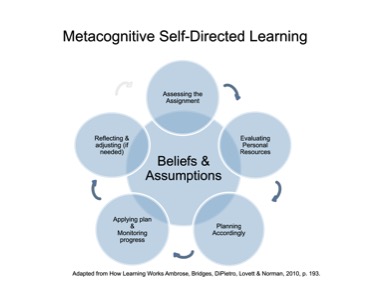

Over the past four years, I have been exploring the concept of metacognition. In many ways, I think metacognition has been a large part of how I work as a practitioner both in my personal practice of reflection and in how I practice the art of teaching. However, it wasn’t until I switched faculty positions that I really started to dive into intentional research and practice around metacognition.

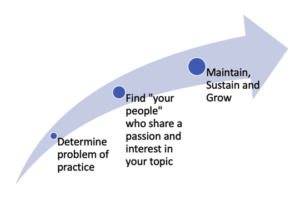

![]() As noted in the “Finding Your People” blog post, this was largely because I had difficulty adjusting to new students at a new school. The challenges that arose prompted me to find ways to meet the needs of my new students in order to support their growth as learners and as people. One of the strategies that quickly arose as a strategy that could help was metacognition.

As noted in the “Finding Your People” blog post, this was largely because I had difficulty adjusting to new students at a new school. The challenges that arose prompted me to find ways to meet the needs of my new students in order to support their growth as learners and as people. One of the strategies that quickly arose as a strategy that could help was metacognition.

I am the kind of teacher who likes to try things. I have done a number of different activities (both research based and more “practice based”) over the past 4 years and have learned much from all of them. However, one practice in particular that stands out to me as having a significant impact on student learning and in the overall experience of the course was the use of learning portfolios. I have used similar strategies previously in both graduate and undergraduate courses, but never with an intentional focus on metacognition. The books, Using Reflection and Metacognition to Improve Student Learning: Across the Disciplines, Across the Academy (New Pedagogies and Practices for Teaching in Higher Education) by Kaplan et al., (2013) and Creating Self Regulated Learners by Nilson (2013), were resources I used (along with other research) to put the pieces together to design and develop the learning portfolio.

I primarily teach two courses: Introduction to Public Health (mostly first-year students) and Health Behavior and Promotion (mostly sophomores and juniors). Both courses serve students in the School of Health Science. I first integrated the learning portfolio into my Health Behavior and Promotion course with great success. I plan to create a learning portfolio for my Introduction to Public Health course this fall and am excited to see how it works!

Overview of the Learning Portfolio

The learning portfolio was a “deliverable” that students worked on for the whole semester. The learning portfolio was connected to a course “e-book” in which I introduced weekly topics and objectives, outlined the class preparation & included prompts for the learning portfolio (more on the “e-book” below). Students kept notes, reflections, and responses to other assignments in their portfolios. In order to support student success, students submitted the portfolios 4 times over the semester (about every 3 weeks). Each time students submitted the portfolio they received a grade based mainly on completeness. I considered “completeness” the extent to which they addressed all prompts.

I should note here that not all of their reflections are necessarily connected to metacognition. However, in most sets of prompts given, the majority of the prompts related to metacognition. Students were asked to reflect specifically their experiences in the course, how their experiences were impacting their learning, connections they are making to the content, their perceptions of the usefulness and applicability of content in their lives, their use (or lack of) metacognitive and self-regulation strategies, etc.

E-Book

One component of the learning portfolio involved responding to prompts in the “e-book”. The “e-book” included the following three “components”: 1) an introduction to the content for each week (and how it connects to previous learning), 2) guidance on what to focus on in the class preparation, and 3) metacognitive reflective questions.

The introduction to the content included connections to the learning objectives (which were also presented in the syllabus), described why they were learning the material and how it connected to previous learning. I hoped that the introduction would help them monitor and evaluate their understanding of the course content week to week and within the broader context of the whole course.

With the class preparation guidance, I was hoping to help students develop task oriented skills. I have often found it a challenge to get students to complete class preparation. Students have also been honest and shared that my concerns around the lack of class preparation completion were not unfounded. I thought that providing some guidance on what to focus on and look for might help increase the number of students completing the class prep and also increase students’ ability to retain the information and be ready to use the content in class. I also hoped that the guidance might also help them with task oriented and evaluative skills.

While I don’t have any specific data about the impacts, I definitely noticed a positive difference in student participation during this semester compared to others. Students also seemed to have a stronger grasp on the content. Of course, there are many reasons that I could attribute to these improvements, but my teaching itself didn’t change that much and the one variable that was definitely different was the “e-book” and learning portfolio.

The final component of the “e-book” were the reflective questions. Questions varied week to to week. Sample questions::

- How does what you read and watched for today connect to your prior knowledge learning? How does it connect to the reading from Monday?

- Review the syllabus and assignments posted in the Assignments folder, what assignments do you feel align with your strengths as a student? Which might be more challenging? Why? What are strategies you could use to help you to be successful?

- What are 3 key points from these readings and the video that you think are important for college students to know?

Each class prep assignment had these kinds of reflective questions for students to activate and connect to prior learning, to monitor and evaluate their learning, and to help them identify their strengths and areas for improvement.

Lessons Learned

Using a learning portfolio in my course taught me many things:

- I have learned that students communicate their thoughts, reflections and experiences in many different ways. Some responses are brief and concise, some are more “stream of consciousness”, and some provide extremely thoughtful and thorough, more polished responses. I learned to focus more on the purpose of the activity (to think about themselves and their learning), rather than the “quality” of their reflections. I felt that my my bias of what I believe a quality reflection “looks like” might impact students’ learning and growth.

- I experienced the value of being able to have a “dialogue” with students through the portfolio though my feedback. Sometimes the feedback was a question, my perspectives, a connection to course content, etc. I saw the learning portfolio as a dialogue between me and the students more than a gradable assignment (though assigning points helps with motivation and completion). Student responses to these questions helped me to connect with students more deeply and provide feedback to support their learning and also add different perspectives than we may have been able to cover in class. I feel that I was able to get to know students a lot better through this model, that I was able to engage differently with each student (which I don’t always get to do in a course) .

- The learning portfolio was also a place where students recorded responses to in-class discussion prompts. Sometimes I would have students respond to discussion prompts before the discussion in class to allow students to gather their thoughts, and sometimes it was after discussion to allow for processing time. I learned that this was a great way to be able to receive responses from all students as I often can’t get around to hear from students when discussing in class and students don’t always feel comfortable speaking up but it is often not because they don’t have valuable contributions. The learning portfolio structure allowed me to “hear from” each student.

- I learned that it takes a little work to get “buy in” from students, which is why I spend about 2 weeks at the start of the semester talking about learning and metacognition. That way, students have a foundation to understand the “why” behind the learning portfolio (and other aspects of the course). However, I believe the time is well spent and that the content and skills they gain from both the class content and the learning portfolio are as important (maybe for some students even more important) than the course content itself.

Conclusion

Adding the learning portfolio to my class has been one of the more impactful strategies I have tried. It is a lot of upfront work and a decent amount of work during the semester if I respond to all students, but I saw a significant improvement in student engagement and student learning. I also felt that I connected more with students and got to know them better. I am looking forward to trying this approach with my first-year students this fall (perhaps another blog post will be in order to share how it goes)!