By: Melissa Terlecki, PhD, Cabrini University PA

“Learning about myself wasn’t easy. Metacognition took way more work than all my other classes, but I learned so much about myself that I hope to apply in the future” – Anonymous Student Quote.

The Question at Hand

What do we want our students to get out of college? Does it extend beyond content – to include skills to potentially last a lifetime? I believe so, and argue that self-awareness and metacognition development should be part of what every college student achieves.

Self-awareness involves understanding one’s strengths and areas for improvement; it’s recognizing how we grow best and optimizing our potential. Metacognition is more than just “thinking about thinking” – it’s applying that self-knowledge to better oneself. Skills and strategies related to self-awareness and metacognition may not come naturally – or easily. Explicitly promoting them both through coursework in college may be a start.

Self-awareness involves understanding one’s strengths and areas for improvement; it’s recognizing how we grow best and optimizing our potential. Metacognition is more than just “thinking about thinking” – it’s applying that self-knowledge to better oneself. Skills and strategies related to self-awareness and metacognition may not come naturally – or easily. Explicitly promoting them both through coursework in college may be a start.

Below are short overviews of two initiatives I have led at my institution, along with some student and faculty feedback and a brief personal reflections. I encourage you to think about ways to incorporate self-awareness and metacognition.

Metacognition in Leadership

I embarked on a journey to include metacognition as part of a Leadership program based on the Social Change Model of Leadership Development. Self-awareness is core to living and leading up to one’s greatest potential in strengths-based development. Metacognition, based on this model, is focused on building positive change in society as a leader at any level. Thus, I built a course around developing self-awareness while linking recognition of one’s skills to leadership potential. My “Metacognition in Leadership” course is open to any of our students, and although part of a Leadership minor, many seek to take it, despite the rumors of the workload.

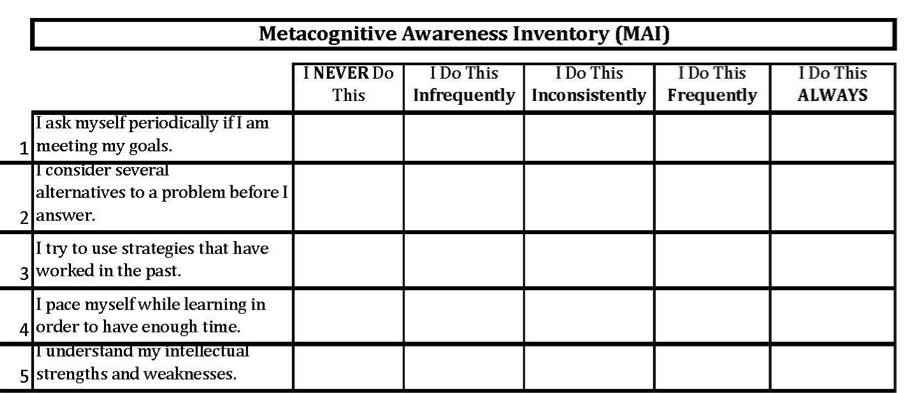

Metacognition is built in every activity and assignment and simulates a flipped classroom. Course feedback shows that students are challenged yet do really well in the course, including self-measured improvements in metacognition. Grades are high and students argue that metacognition should be taught to everybody.

“Why is this not taught in grade-school? I would’ve done much better…” – Michelle Brzoska, Student.

“I believe for me it was challenging to dig deep into my traits and values. We just do things and say things without thinking about them. However, this course pushed me to consider those traits and reflect on them. Most of the time we do not have the time to reflect on ourselves and I believe sometimes it leads to false perceptions about ourselves.” – Maria Khan, Student.

Metacognition in First-Year Experience

I also sought to embed self-awareness in first-year experience (FYE) programming, as we know self-awareness of interests and strengths can lead to persistence (and retention) in academic settings. In 2020, our FYE programming was about to undergo revision. I was asked to step in to provide a metacognitive framework for students’ college success, as realizing their best path to learning and to their eventual major/s is the goal of such a course.

Students learned about topics such as self-regulation, emotional intelligence, motivation and achievement, among other areas, which were directly connected to student self-assessments. Faculty utilized regular reflections and feedback, with weekly check-ins and academic advising. Course feedback from both instructors and students was favorable: students enjoyed learning about themselves and faculty appreciated this, yet commented on the challenging nature of teaching metacognition (given faculty teaching our FYE course are from all different disciplines):

“Content was good but challenging to take on. Students got a lot out of it in only one semester. Faculty need more training in metacognition” – Anonymous Faculty Quote.

Reflections on Interventions

Adding metacognitive content AND pedagogy takes work. And time. And a lot of grading and feedback. It is an iterative process and is not static or traditional by any means. Students may resist active engagement that forces them beyond their comfort zones in passive learning, and especially self-awakening. This is a different type of learning than students are used to or expect at the college level, perhaps given their previous experiences at K-12. It takes more effort on both the student’s and the instructor’s parts.

Both students and faculty need training in metacognition: the pedagogy, the routine self-reflection and feedback. I provide metacognition training/workshops to institutions for both faculty and staff. I have seen and heard the impact these techniques can have on teaching and learning. For metacognition to stick, however, it needs to be more than quick tricks – metacognition is a “lifestyle” change in pedagogy for teachers. It has to be a new way of learning and self-discovery for learners. Again, this is not easy, but is well worth the effort, as benefits of self-awareness extend beyond the classroom to our relationships, our jobs, and our lives.

“I think it’s important for people to learn metacognition because of the awareness and understanding you get from it. Once you learn more about it, it’ll be easier to control your emotions and be able to comprehend how others feel” – Orlyany Sanchez, Student.

“I hope I can keep reflecting after this course is over. It has already changed how I think and feel about other people” – Anonymous Student Quote.

“It is extremely vital that we learn about metacognition to understand ourselves better so we can interact with others well. There were times where I was not able to connect with others because I was not able to connect with myself. But this [course] showed me the importance of knowing oneself as well as applying to my future” – Maria Khan, Student.

—————–

Note: Feel free to contact the author, Melissa Terlecki, for more information on course materials and/or metacognition workshop availability to bring to your school! (mst723@cabrini.edu)

Note 2: Catch my talk on metacognition at the 2021 American Psychological Association virtual conference as the Harry Kirke Wolfe Lecturer! (12-14 August; see https://convention.apa.org/)