Clinical Supervision is a model of supervisor (or peer) review that stresses the benefits of a teacher-led self-analysis of teaching in the post-conference versus a conference dominated by the judgments of the supervisor. Through self-reflection, teachers are challenged to use metacognitive processes to determine the effects of their teaching decisions and actions on student learning. The Clinical Supervision model is equally applicable to all levels of schooling and all disciplines. This video walks you through the process.

Author: Cynthia Desrochers

Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Reflection, Anyone?

By Cynthia Desrochers, California State University Northridge

I once joked with my then university president that I’d seen more faculty teach in their classrooms than she had. She nodded in agreement. I should have added that I’d seen more than the AVP for Faculty Affairs, all personnel committees, deans, or chairpersons. For some reason, university teaching is done behind closed doors, no peering in on peers unless for personnel reviews. We attempted to change that at CSU Northridge when I directed their faculty development center from 1996-2005. Our Faculty Reciprocal Peer Coaching program typically drew a dozen or more cross-college dyads over the dozen semesters it was in existence. The program’s main goal was teacher self-reflection.

I believe I first saw the term peer coaching when reading a short publication by Joyce and Showers (1983). What stuck me was their assertion that to have any new complex teaching innovation become part of one’s teaching repertoire required four steps: 1) understanding the theory/knowledge base undergirding the innovation, 2) observing an expert who is modeling how to do the innovation, 3) practicing the innovation in a controlled setting with coaching (e.g., micro-teaching in a workshop) and 4) practicing the innovation in one’s own classroom with coaching. They maintained that without all four steps, the innovation taught in a workshop would likely not be implemented in the classroom. Having spent much of my life teaching workshops about using teaching innovations, these steps became my guide, and I still use them today. In addition, after many years of coaching student teachers at UCLA’s Lab School, I realized that they were more likely to apply teaching alternatives that they identified and reflected upon in the post-conference than ones that I singled out. That is, they learned more from using metacognitive practices than from my direct instruction, so I began formulating some of the thoughts summarized below.

Fast forward many years to this past year, where I co-facilitated a yearlong eight-member Faculty Learning Community (FLC) focused on implementing the following Five Gears for Activating Learning: Motivating Learning, Organizing Knowledge, Connecting Prior Knowledge, Practicing with Feedback, and Developing Mastery [see previous blog]. With this FLC, we resurrected peer coaching on a voluntary basis in order to promote conscious use of the Five Gears in teaching. All eight FLC members not only volunteered to pair up for reciprocal coaching of one another, but they were eager to do so.

I was asked by one faculty member why is it called coaching, because an athletic coach often tells players what to do, versus helping them self-reflect. I responded that it’s because Joyce and Showers’ study looked at the research on training athletes and what that required for skill transfer. They showed the need for many practice sessions combined with coaching in order to achieve mastery of any new complex move, be it on the playing field or in the classroom. However, their point of confusion was noted, so now I refer to the process as Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Reflection. This reflective type of peer coaching applies to cross-college faculty dyads who are seeking to more readily apply a new teaching innovation.

Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Refection applies all or some of the five phases of the Clinical Supervision model described by Goldhammer(1969), which include: pre-observation conference, observation and data collection, data analysis and strategy, post-observation conference, and post-conference analysis. However, it is in the post-conference phase where much of the teacher self-reflection occurs and where the coach can benefit from an understanding of post-conference messages.

Prior to turning our FLC members loose to peer coach, we held a practicum on how to do it. And true to my statement above, I applied Joyce and Showers’ first three steps in our practicum (i.e., I explained the theory behind peer coaching, modeled peer coaching, and then provided micro-practice of a videotaped lesson taught by one of our FLC members). But in the micro-practice, right out of the gate, faculty coaches began telling the teacher how she used the Five Gears versus prompting her to reflect upon her own use first. Although I gently provided feedback in an attempt to redirect the post-conferences from telling to asking, it was a reminder of how firmly ingrained this default position has become with faculty, where the person observing a lesson takes charge and provides all the answers when conducting the post-conference. The reasons for this may include 1)prior practice as supervisors who are typically charged with this role, 2) the need to show their analytic prowess, or 3) the desire to give the teacher a break from doing all the talking. Whatever the reason, we want the teacher doing the reflective analysis of her own teaching and growing those dendrites as a result.

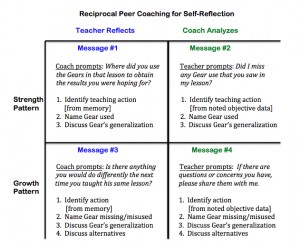

After this experience with our FLC, I crafted the conference-message matrix below and included conversation-starter prompts. Granted, I may have over-simplified the process, but it illustrates key elements for promoting Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Reflection. Note that the matrix is arranged into four types of conference messages: successful and unsuccessful teaching-learning situations, where the teacher identifies the topic of conversation after being prompted by the coach (messages #1 and #3) and successful and unsuccessful teaching-learning situations, where the coach identifies the topic of conversation after being prompted by the teacher (messages #2 and #4). The goal of Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Reflection is best achieved when the balance of the post-conference contains teacher self-reflection; hence, messages #1 and #3 should dominate the total post-conference conversation. Although the order of messages #1 through #4 is a judgment call, starting with message #1permits the teacher to take the lead in identifying and reflecting upon her conscious use of the Gears and their outcome –using her metacognition—versus listening passively to the coach. An exception to beginning with message #1 may be that the teacher is too timid to sing her own praises, and in this instance the coach may begin with message #2 when this reluctance becomes apparent. Note further that this model puts the teacher squarely in the driver’s seat throughout the entire post-conference; this is particularly important when it comes to message #4, which is often a sensitive discussion of unsuccessful teaching practices. If the teacher doesn’t want another’s critique at this time, she is told not to initiate message #4, and the coach is cautioned to abide this decision.

The numbered points under each of the four types of messages are useful components for discussion during each message in order to further cement an understanding of which Gear is being used and its value for promoting student learning: 1) Identifying the teaching action from the specific objective data collected by the coach (e.g., written, video, or audio) helps to isolate the cause-effect teaching episode under discussion and its effect on student learning. 2) Naming the Gear (or naming any term associated with the innovating being practiced) increases our in-common teaching vocabulary, which is considered useful for any profession. 3) Discussing the generalization about how the Gear helps students learn reiterates its purpose, fostering motivation to use it appropriately. And 4) crafting together alternative teaching-learning practices for next time expands the teacher’s repertoire.

The FLC faculty reported that their classroom Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Reflection sessions were a success. Specifically, they indicated that they used the Five Gears more consciously after discussing them during the post-conference; that the Five Gears were beginning to become part of their teaching vocabulary; and that they were using the Five Gears more automatically during instruction. Moreover, unique to message #2, it provided the benefit of having one’s coach identify a teacher’s unconscious use of the Five Gears, increasing the teacher’s awareness of themselves as learners of an innovation, all of which serve to increase metacognition.

When reflecting upon how we might assist faculty in implementing the most promising research-based teaching-learning innovations, I see a system where every few years we allot reassigned time for faculty to engage in Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Reflection.

References

Goldhammer, R. (1969). Clinical supervision. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Joyce, B. & Showers, B. (1983). Power in staff development though research on training. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Thinking about How Faculty Learn about Learning

By Cynthia Desrochers, California State University Northridge

Lately, two contradictory adages have kept me up nights: “K.I.S.S. – Keep It Simple, Stupid” (U.S. Navy) and “For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong” (H.L. Mencken). Which is it? Experts have a wealth of well-organized, conditionalized, and easily retrievable knowledge in their fields (Bradford, et al., 2000). This may result in experts skipping over steps when they teach a skill that has become automatic to them. But where does this practice leave our novice learners who need to be taught each small step—almost in slow motion—to begin to grasp a new skill?

I have just completed co-facilitating five of ten scheduled faculty learning community (FLC) seminars in a yearlong Five GEARS for Activating Learning FLC. As a result of this experience, my takeaway note to self now reads in BOLD caps: (1) keep it simple in the early stages of learning and (2) model the entire process and share my thinking out loud—no secrets hidden behind the curtains!

The Backstory

The Five Gears for Activating Learning project at California State University, Northridge, began in fall 2012. It was my idea, and I asked seven university-wide faculty leaders to join me in a grassroots effort. Our goals were to improve student learning from inside the classroom (vs. policy modifications), promote faculty use of the current research on learning, provide a lens for judging the efficacy of various teaching strategies (e.g., the flipped classroom), and develop a common vocabulary for use campuswide (e.g., personnel communications). Support for this project came from the University Provost and the dean of the Michael D. Eisner College of Education in the form of reassigned time for me and 3-unit buyouts for each of the eight FLC members, spread over the entire academic year, 2014-15.

We read as a focus book How Learning Works: 7 Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching (Ambrose, et al., 2010). We condensed Ambrose’s seven principles to five GEARS, one of which is Developing Mastery, which we defined as deep learning, reflection, and self-direction—critical elements of metacognition and the focus of this blog site.

On Keeping It Simple

I have been in education for forty-five years, yet I’m having many light-bulb moments with this FLC group – I’m learning something new, or reorganizing prior knowledge, or having increased clarity. Hence, I’ve given a lot of thought to the conflict between keeping it simple and omitting some important elements versus sharing more complex definitions and relationships and overwhelming our FLC members. My rationale for choosing simple: If I am still learning about how learning works, how can I expect new faculty—who teach Political Science, Business Law, Research Applications, and African Americans in Film, all without benefit of a teaching credential—to process some eighty years of research on learning in two semesters?

In opting for the K.I.S.S. approach, we have developed a number of activities and tools that scaffold learning to use the five GEARS in our teaching; moreover, each activity or tool models explicitly with faculty some practices we are encouraging them to use with their students. This includes (1) reflective writing in the form of learning logs and diaries, (2) an appraisal instrument to self-assess their revised (using the GEARS) spring 2015 course design, and (3) a class-session plan to scaffold their use of the GEARS. [See the detailed descriptions given in the handout resource posted on this site.] I hope to have some results data regarding their use in my spring blog.

Looking to next semester, our spring FLC projects will likely center around not only teaching the redesigned five GEARS course but also disseminating the five GEARS campuswide. As a direct result of the Daily Diary that FLC members kept for three weeks on others’ use and misuse of the five GEARS, they want to share our work. [See handout for further description of the Daily Diaries.] Dissemination possibilities include campus student tour guides, colleagues who teach a common course, Freshman Seminar instructors, librarians, and the Career Center personnel. If another adage is true, “Tell me and I forget, teach me and I may remember, involve me and I learn” (Benjamin Franklin), our FLC faculty will likely move of their own accord along the continuum from a simple to complex understanding of the five GEARS in their efforts to teach the five GEARS to others on campus.

A Word about GEARS

Why is this blog not focusing solely on the metacognition gear, which we call Developing Mastery? The simple answer is that learning is so intertwined that all the GEARS likely support metacognition in some way. However, any one of the activities or tools we have employed can be modified to limit the scope to your definition of metacognition. Our postcard below shows all five GEARS: