By Charity S. Peak, Ph.D.

What does it take to become an exceptional college teacher? As many of us have learned, there’s much more to the art and science of teaching than merely knowing the content. Still, every year, several new faculty members begin teaching with the false assertion that solely learning more about their subject will lead to success in the classroom. Instead, metacognition about their development as a teacher could help propel them into their new roles with greater ease. Below is an appeal for new faculty to embrace metacognition about their instruction by understanding their developmental path with college teaching.

————-

Dear New Faculty,

Congratulations on starting your new role as a college teacher! You’ve worked hard to get to this point, spending years in class and writing that thesis or dissertation. Now you get to share all of that knowledge with aspiring students. Your passion will hopefully convert several of them into majoring in your discipline or even becoming your research prodigies. Your optimism is contagious and inspiring.

Despite the fact that you now hold an advanced degree, your learning is not over. In fact, the journey to becoming an effective teacher has just begun. Before you step into that classroom, take a strategic pause to become metacognitive about your teaching, not just your content. You must now design a course that is meaningful for your students. Sure, you can simply use the materials provided by the textbook publisher, especially those well-designed PowerPoint slides, but did you know college teaching requires so much more? Did you know there are developmental stages for becoming an effective college teacher?

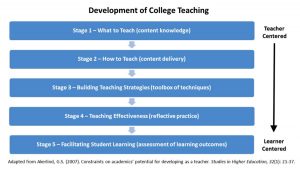

Akerlind (2007) shares brilliant insights about progressing from a teacher-centered to a learner-centered approach. In order to focus on student learning, faculty need to become aware of how they are teaching and begin to adapt their instruction to best meet the needs of their students. In other words, effective college faculty engage in metacognition about their instruction through awareness of teaching strategies, reflection about their practice, and self-regulation of teaching methods based on student learning needs. To this end, Akerlind asserts that college teachers move through the following developmental stages:

If these stages hold true, what does this mean for you? As Akerlind shares, new teachers often expend most of their energies on understanding their disciplinary content really well. You may spend great effort reading the textbook and researching the topics as much as possible. In all likelihood, much of your class time will be spent lecturing or presenting information (perhaps using those textbook slides), a very teacher-centered style. In reality, if you take this approach, you may learn more than your students this year because you spent greater time and energy mastering the material than they did.

Over time, however, you may discover that students are not participating in class like you want, or you may notice dwindling attendance. Student evaluations might even reflect dissatisfaction with your teaching style. Don’t be dismayed; don’t give up. You will begin to shift into Akerlind’s next developmental stage by considering alternative methods for content delivery. You will move toward focusing on how to teach rather than what to teach, especially now that you feel more comfortable with the content of the course. During this stage, you will gain greater metacognition about your teaching.

Through trial and error, you will begin to explore and experiment with a variety of teaching strategies, increasing your toolbox of techniques from which to use. Trying these new strategies will not be sufficient, though. You will need to select evidence-based strategies drawn from the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) literature, and you will need to reflect on how well the new methods worked (also called reflective practice). Through reflection, you will begin to see which teaching techniques fit your personal style and subject matter. You will also begin to seek feedback, particularly from students, about how well these new strategies are being received.

Ultimately, though, you will discover that student satisfaction and snazzy teaching techniques fall flat if your students aren’t learning from the course. As Akerlind claims, you will move into the final developmental stage by designing your instruction and curriculum to be singularly focused on learning outcomes. You will search for a balance between being liked as a teacher to challenging students to transform their thinking. You may even embrace this positive restlessness and seek continuous improvement with your teaching each semester.

So why should you care about these stages of college teaching development? Because perhaps seeing your teaching as a journey and not a fixed goal will help you to be patient with yourself as you try new techniques and begin to feel overwhelmed. Perhaps metacognition about your future development will help you to progress more quickly through these stages to focusing on student learning rather than your instruction style. Go ahead and acknowledge that your first semester or two may be focused heavily on understanding the content at hand, but over time, try to embrace metacognitive instruction by leveraging knowledge about teaching and intentional awareness in the classroom to move toward more sophisticated methods for delivering that content. Become reflective practitioners who care about student feedback and continuous improvement, but eventually shift your focus to improving student learning outcomes.

The journey to becoming an effective college teacher will not happen overnight, even with this new metacognition you have, but rest assured that it will be rewarding and meaningful. In Bain’s (2004) pivotal work, What the Best College Teachers Do, you will discover that it could take up to 10 years to become an effective faculty member. However, maintaining metacognition about these stages of development will likely put you on target sooner, working toward a learner-centered approach to teaching. Good luck!

Resources:

Akerlind, G.S. (2007). Constraints on academics’ potential for developing as a teacher. Studies in Higher Education, 32(1): 21-37. doi: 10.1080/03075070601099416

Bain, K. (2004). What the best college teachers do. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.