by Steven Fleisher, California State University

Michael Roberts, DePauw University

Michelle Mason, University of Wyoming

Lauren Scharff, U. S. Air Force Academy

Ed Nuhfer, Guest Editor, California State University (retired)

When I first entered graduate school, I was flourishing. I was a flower in full bloom. My roots were strong with confidence, the supportive light from my advisor gave me motivation, and my funding situation made me finally understand the meaning of “make it rain.” But somewhere along the way, my advisor’s support became only criticism; where there was once warmth, there was now a chill, and the only light I received came from bolts of vindictive denigration. I felt myself slowly beginning to wilt. So, finally, when he told me I did not have what it takes to thrive in academia, that I wasn’t cut out for graduate school, I believed him… and I withered away. (actual co-author experience)

After reading the entirety of this two-part blog entry, return and read the shared experience above once more. You should find that you have an increased ability to see the connections there between seven elements: (1) affect, (2) cognitive development, (3) metacognition, (4) self-assessment, (5) feedback, (6) privilege, and (7) mindset.

The study of self-assessment as a valid component of learning, educating, and understanding opens up fascinating areas of scholarship for new exploration. This entry draws on the same paired-measures research described in the previous blog entries of this series. Here we explain how measuring self-assessment informs understanding of mindset and feedback. Few studies connect self-assessment with mindset, and almost none rest on a sizeable validated data set.

Mindset, self-assessment, and privilege

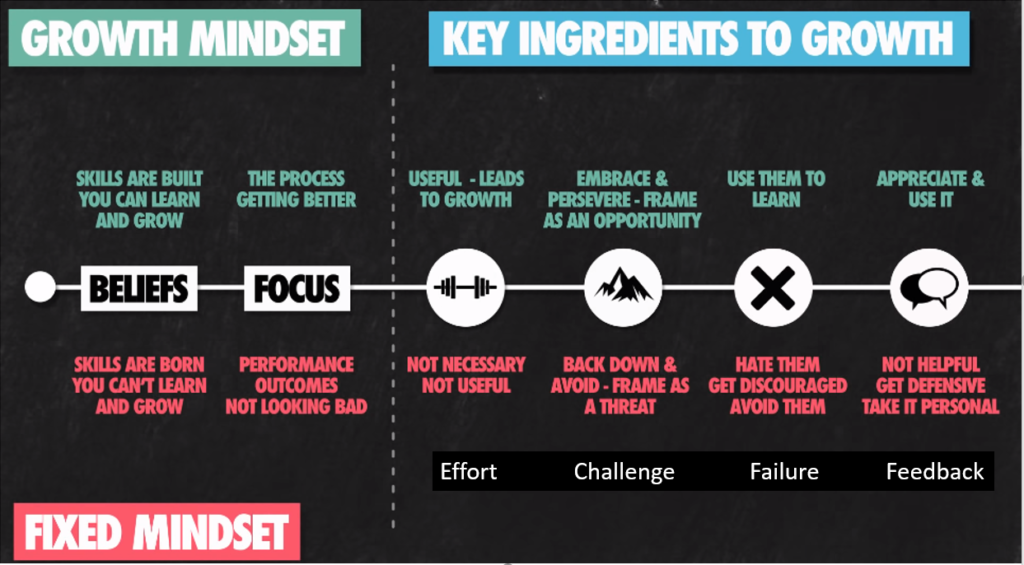

Mindset theory proposes that individuals lean toward one of two mindsets (Dweck, 2006) that differ based on internalized beliefs about intelligence, learning, and academics. According to Dweck and others, people fall along a continuum that ranges from having a fixed mindset defined by a core belief that their intelligence and thinking abilities remain fixed, and effort cannot change them. In contrast, having a growth mindset comes with the belief that, through their effort, people can expand and improve their abilities to think and perform (Figure 1).

Indeed, a growth mindset has support in the stages of intellectual, ethical, and affective development discovered by Bloom & Krathwohl and William Perry mentioned earlier in this series. However, mindset theory has evolved into making broader claims and advocating that being in a state of growth mindset also enhances performance in high-stakes functions such as leadership, teaching, and athletics.

Figure 1. Fixed – growth mindset tendencies. (From https://trainugly.com/portfolio/growth-mindset/)

Do people choose their mindset or do their experiences place them in their positions on the mindset continuum? Our Introduction to this series disclosed that people’s experiences from degrees of privilege influence their positioning along the self-assessment accuracy continuum, and self-assessment has some commonalities with mindset. However, a focused, evidence-based study of privilege on determining mindset inclination seems lacking.

Our Introduction to this series indicated that people do not choose their positions along the self-assessment continuum. People’s cumulative experiences place them there. Their positions result from their individual developmental histories, where degrees of privilege influence the placement through how many experiences an individual has that are relevant and helpful to building self-assessment accuracy. The same seems likely for determining positions along the mindset continuum.

Acting to improve equity in educational success

Because the development during pre-college years primarily occurs spontaneously by chance rather than by design, people are rarely conscious of how everyday experiences form their dispositions. College students are unlikely even to know their positions on either continuum unless they receive a diagnostic measure of their self-assessment accuracy or their tendency toward a growth or a fixed mindset. Few get either diagnosis anywhere during their education.

Adapting a more robust growth mindset and acquiring better self-assessment accuracy first requires recognizing that these dispositions exist. After that, devoting systematic effort to consciously enlisting metacognition during learning disciplinary content seems essential. Changing the dispositions takes longer than just learning some factual content. However, the time required to see measurable progress can be significantly reduced by a mentor/coach who directs metacognitive reflection and provides feedback.

Teaching self-assessment to lower-division undergraduates by providing numerous relevant experiences and prompt feedback is a way to alleviate some of the inequity produced by differential privilege in pre-college years. The reason to do this early is to allow students time in upper-level courses to ultimately achieve healthy self-efficacy and graduate with the capacity for lifelong learning. A similar reason exists for teaching students the value of affect and growth mindset by providing awareness, coaching, and feedback. Dweck describes how achieving a growth mindset can mitigate the adverse effects of inequity in privilege.

Recognizing good feedback

Dweck places high value on feedback for achieving the growth mindset. The Figure 1 in our guest series’ Introduction also emphasizes the importance of feedback in developing self-assessment accuracy and self-efficacy during college.

Depending on a person’s beliefs about their particular skill to address a challenge, they will respond in predictable ways when a skill requires effort, when it seems challenging, when effort affects performance, and when feedback informs performance. Those with a fixed mindset realize that feedback will indicate imperfections, which they take as indicative of their fixed ability rather than as applicable to growing their ability. To them, feedback shames them for their imperfections, and it hurts. They see learning environments as places where stressful competitions occur between their own and others’ fixed abilities. Affirmations of success rest in grades rather than growing intellectual ability.

Those with a growth mindset value feedback as illuminating the opportunities for advancing quickly in mastery during learning. Sharing feedback with peers in their learning community is a way to gain pleasurable support from a network that encourages additional effort. There is little doubt which mindset promotes the most enjoyment, happiness, and lasting friendships and generates the least stress during the extended learning process of higher education.

Dweck further stresses the importance of distinguishing feedback that is helpful from feedback that is damaging. Our lead paragraph above revealed a devastating experience that would influence any person to fear feedback and seek to avoid it. A formative influence that disposes us to accept or reject feedback likely lies in the nature of feedback that we received in the past. A tour through traits of Dweck’s mindsets suggests many areas where self-perceptions can form through just a single meaningful feedback event.

Australia’s John Hattie has devoted his career to improving education, and feedback is his specialty area. Hattie concluded that feedback is “…the most powerful single moderator that enhances achievement” and noted in this University of Auckland newsletter “…arguably the most critical and powerful aspect of teaching and learning.”

Hattie and Timperley (2007) synthesized many years of studies to determine what constitutes feedback helpful to achievement. In summary, valuable feedback focuses on the work process, but feedback that is not useful focuses on the student as a person or their abilities and communicates evaluative statements about the learner rather than the work. Hattie and Dweck independently arrived at the same surprising conclusion: even praise directed at the person, rather than focusing on the effort and process that led to the specific performance, reinforces a fixed mindset and is detrimental to achievement.

Professors seldom receive mentoring on how to provide feedback that would promote growth mindsets. Likewise, few students receive mentoring on how to use peer feedback in constructive ways to enhance one another’s learning.

Takeaways

Scholars visualize both mindset and self-assessment as linear continuums with two respective dispositions at each of the ends: growth and fixed mindsets and perfectly accurate and wildly inaccurate self-assessments. In this Part 1, we suggest that self-assessment and mindset have surprisingly close connections that scholars have scarcely explored.

Increasing metacognitive awareness seems key to tapping the benefits of skillful self-assessment, mindset, and feedback and allowing effective use of the opportunities they offer. Feedback seems critical in developing self-assessment accuracy and learning through the benefits of a growth mindset. We further suggest that gaining benefit from feedback is a learnable skill that can influence the success of individuals and communities. (See Using Metacognition to Scaffold the Development of a Growth Mindset, Nov 2022.)

In Part 2, we share findings from our paired measures data that partially explain the inconsistent results that researchers have obtained between mindset and learning achievement. Our work supports the validity of mindset and its relationship to cognitive competence. It allows us to make recommendations for faculty and students to apply this understanding to their advantage.

References

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York: Random House.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Heft, I. & Scharff, L. (July 2017). Aligning best practices to develop targeted critical thinking skills and habits. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Vol 17(3), pp. 48-67. http://josotl.indiana.edu/article/view/22600

Isaacson, Randy M., and Frank Fujita. 2006. “Metacognitive Knowledge Monitoring and Self-Regulated Learning: Academic Success and Reflections on Learning.” Journal of Scholarship of Teaching and learning6, no. 1: 39–55. Retrieved from https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ854910

Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2020). What can be learned from growth mindset controversies? American Psychologist, 75(9), 1269–1284. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000794