by Dana Melone, Cedar Rapids Kennedy High School

Every year I start my psychology class by asking the students some true or false statements about psychology. These statements are focused on widespread beliefs about psychology and the capacity to learn that are not true or have been misinterpreted. Here are just a few:

- Myth 1: People learn better when we teach to their true or preferred learning style

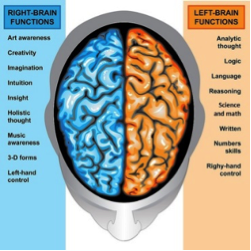

- Myth 2: People are more right brained or left brained

- Myth 3: Personality tests can determine your personality type

Many of these myths are still widely believed and used in the classroom, in staff professional development, in the workplace to make employment decisions, and so much more. Psychological myths in the classroom hurt metacognition and learning. All of these myths allow us to internalize a particular aspect of ourselves we believe must be true, and this seeps into our cognition as we examine our strengths and weaknesses.

Myth 1: People learn better when we teach to their true or preferred learning styles

The learning style myth persists. A Google search of learning styles required me to proceed to page three of the search before finding information on the fallacy of the theory. The first two pages of the search contained links to tests to find your learning style, and how to use your learning style as a student and at work. In Multiple Intelligences, by Howard Gardner (1983), the author developed the theory of multiple intelligences. His idea theorizes that we have multiple types of intelligences (kinesthetic, auditory, visual, etc.) that work in tandem to help us learn. In the last 30 years his idea has become synonymous with learning styles, which imply we each have one predominant way that we use to learn. There is no research to support this interpretation of learning styles, and Gardner himself has discussed the misuse of his theory. If we perpetuate this learning styles myth as educators, employees, or employers, we are setting ourselves up and the people we influence to believe they can only learn in the fashion that best suits them. This is a danger to metacognition. For example, if I am examining why I did poorly on my last math test and I believe I am a visual learner, I may attribute my poor grade to my instructor’s use of verbal presentation instead of accurately reflecting on the errors I made in studying or calculation.

Myth 2: People are more right brained or left brained

Research on the brain indicates a possible difference between the right and left-brain functions. Most research up to this point examines the left brain as our center for spoken and written language while the right brain controls visual, imagery, and imaginative functions among others. The research does not indicate, however, that a particular side works alone on this task. This knowledge of the brain has led to the myth that if we perceive ourselves as better at a particular topic like art for example, we must be more right brained. In one of numerous studies dispelling this myth, researchers used Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) to examine the brain while completing various “typical” right and left brained tasks. This research clearly showed what psychologists and neurologists have known for some time. The basic functions may lie in those areas, but the two sides of the brain work together to complete these tasks (Nielsen, Zielenski, et. al., 2013). How is this myth hurting metacognition? Like Myth 1, if we believe we are predetermined to a stronger functioning on particular tasks, we may avoid tasks that don’t lie with that strength. We may also use incorrect metacognition in thinking that we function poorly on something because of our “dominant side.”

Myth 3: Personality tests can determine your personality type

In the last five years I have been in a variety of work-related scenarios where I have been given a personality test to take. These have ranged from providing me with a color that represents me or a series of letters that represents me. In applying for jobs, I have also been asked to undertake a personality inventory that I can only assume weeds out people they feel don’t fit the job at hand. The discussion / reflection process following these tests is always the same. How might your results indicate a strength or weakness for you in your job and in your life, and how might this affect how you work with people who do and do not match the symbolism you were given? Research shows that we tend to agree with the traits we are given if those traits contain a general collection of mostly positive and but also a few somewhat less positive characteristics. However, we need to examine why we are agreeing. We tend not to think deeply when confirming our own beliefs, and we may be accidentally eliminating situational aspects from our self-metacognition. This is also true when we evaluate others. We shouldn’t let superficial assumptions based on our awareness of our own or someone else’s personality test results overly control our actions. For example, it would be short-sighted to make employment decisions or promotional decisions based on assumptions that, because someone is shy, they would not do well with a job that requires public appearances.

Dispelling the Myths

The good news is that metacognition itself is a great way to get students and others to let go of these myths. I like to address these myths head on. A quick true false exercise can get students thinking about their current beliefs on these myths. Then I get them talking and linking with better decision-making processes. For example, I ask what is the difference between a theory or correlation and an experiment? An understanding of what makes good research and what might just be someone’s idea based on observation is a great way to get students thinking about these myths as well as all research and ideas they encounter. Another great way to induce metacognition on these topics is to have students take quizzes that determine their learning style, brain side, and personality. Discuss the results openly and engage students in critical thinking about the tests and their results. How and why do they look to confirm the results? More importantly what are examples of the results not being true for them? There are also a number of amazing Ted Talks, articles and podcasts on these topics that get students thinking in terms of research instead of personal examples. Let’s take it beyond students and get the research out there to educators and companies as well. Here are just a few resources you might use:

Hidden Brain Podcast: Can a Personality Test Tell Us About Who We Are?: https://www.npr.org/2017/12/04/568365431/what-can-a-personality-test-tell-us-about-who-we-are

10 Myths About Psychology Debunked: Ben Ambridge: https://tedsummaries.com/2015/02/12/ben-ambridge-10-myths-about-psychology-debunked/

The Left Brain VS. Right Brain Myth: Elizabeth Waters: https://ed.ted.com/lessons/the-left-brain-vs-right-brain-myth-elizabeth-waters

Learning Styles and the Importance of Critical Self-Reflection: Tesia Marshik: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=855Now8h5Rs

The Myth of Catering to Learning Styles: Joanne K. Olsen: https://www.nsta.org/publications/news/story.aspx?id=52624