by Polly R. Husmann, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Anatomy & Cell Biology, Indiana University School of Medicine – Bloomington

Intro: The second post of “The Evolution of Metacognition” miniseries is written by Dr. Polly Husmann, and she reflects on her experiences teaching undergraduate anatomy students early in their college years, a time when students have varying metacognitive abilities and awareness. Dr. Husmann also shares data collected that demonstrate a relationship between students’ metacognitive skills, effort levels, and final course grades. ~ Audra Schaefer, PhD, guest editor

————————————————————————————————–

I would imagine that nearly every instructor is familiar with the following situation: After the first exam in a course, a student walks into your office looking distraught and states, “I don’t know what happened. I studied for HOURS.” We know that metacognition is important for academic success [1, 2], but undergraduates often struggle with how to identify study strategies that work or to determine if they actually “know” something. In addition to metacognition, recent research has also shown that repeated recall of information [3] and immediate feedback also improve learning efficiency [4]. Yet in large, content-heavy undergraduate classes both of these goals are difficult to accomplish. Are there ways that we might encourage students to develop these skills without taking up more class time?

Online Modules in an Undergraduate Anatomy Course

I decided to take a look at this through our online modules. Our undergraduate human anatomy course (A215) is a large (400+) course mostly taken by students planning to go into the healthcare fields (nursing, physical therapy, optometry, etc.). The course is comprised of both a lecture (3x/week) and a lab component (2x/week) with about forty students in each lab section. We use the McKinley & O’Loughlin text, which comes with access to McGraw-Hill’s Connect website. This website includes an e-book, access to online quizzes, A&P Revealed (a virtual dissection platform with images of cadavers) and instant grading. Also available through the MGH Connect site are LearnSmart study modules.

These modules were incorporated into the course along with the related electronic textbook as optional extra credit assignments about five years ago as a way to keep students engaging with the material and (hopefully) less likely to just cram right before the tests. Each online module asks questions over a chapter or section of a chapter using a variety of multiple-choice, matching, rank order, fill-in-the-blank, and multiple answer questions. For each question, students are not only asked for their answer, but also asked to rank their confidence for their answer on a four-point Likert scale. After the student has indicated his/her confidence level, the module will then provide immediate feedback on the accuracy of their response.

During each block of material (4 total blocks/semester) in our anatomy course during the Fall 2017 semester, 4 to 9 LearnSmart modules were available and 2 were chosen by the instructor after the block was completed to be included for up to two points of extra credit (total of 16 points out of 800). Given the frequency of the opening scenario, I decided to take a look at these data and see what correlations existed between the LearnSmart data and student outcomes in our course.

Results

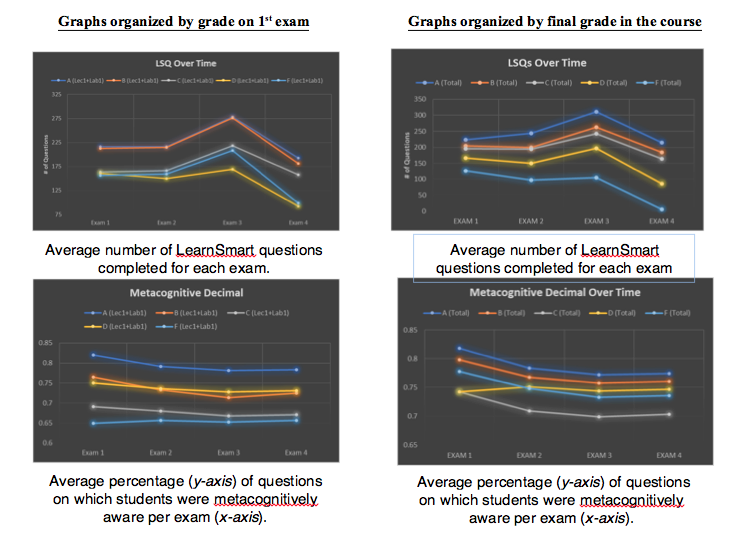

The graphs (shown below) illustrated that the students who got As and Bs on the first exam had done almost exactly the same number of LearnSmart practice questions, which was nearly fifty more questions than the students who got Cs, Ds, or Fs. However, by the end of the course the students who ultimately got Cs were doing almost the exact same number of practice questions as those who got Bs! So they’re putting the same effort into the practice questions, but where is the problem?

The big difference is seen in the percentage of these questions for which each group was metacognitively aware (i.e., accurately confident when putting the correct answer or not confident when putting the incorrect answer). While the students who received Cs were answering plenty of practice questions, their metacognitive awareness (accuracy) was often the worst in the class! So these are your hard-working students who put in plenty of time studying, but don’t really know when they accurately understand the material or how to study efficiently.

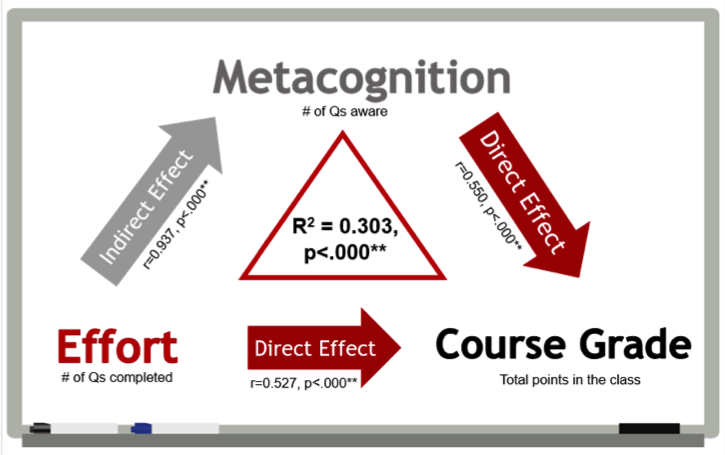

The statistics further confirmed that both the students’ effort on these modules and their ability to accurately rate whether or not they knew the answer to a LearnSmart practice question were significantly related to their final outcome in the course. (See right-hand column graphs.) In addition to these two direct effects, there was also an indirect effect of effort on final course grades through metacognition. So students who put in the effort through these practice questions with immediate feedback do generally improve their metacognitive awareness as well. In fact, over 30% of the variation in final course grades could be predicted by looking at these two variables from the online modules alone.

Effort has a direct effect on course grade while also having an indirect effect via metacognition.

Take home points

- Both metacognitive skills (ability to accurately rate correctness of one’s responses) and effort (# of practice questions completed) have a direct effect on grade.

- The direct effect between effort and final grade is also partially mediated by metacognitive skills.

- The amount of effort between students who get A’s and B’s on the first exam is indistinguishable. The difference is in their metacognitive skills.

- By the end of the course, C students are likely to be putting in just as much effort as the A & B students; they just have lower metacognitive awareness.

- Students who ultimately end up with Ds & Fs struggle to get the work done that they need to. However, their metacognitive skills may be better than many C level students.

Given these points, the need to include instruction in metacognitive skills in these large classes is incredibly important as it does make a difference in students’ final grades. Furthermore, having a few metacognitive activities that you can give to students who stop into your office hours (or e-mail) about the HOURS that they’re spending studying may prove more helpful to their final outcome than we realize.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by a Scholarship of Teaching & Learning (SOTL) grant from the Indiana University Bloomington Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Theo Smith was instrumental in collecting these data and creating figures. A special thanks to all of the students for participating in this project!

References

1. Ross, M.E., et al., College Students’ Study Strategies as a Function of Testing: An Investigation into Metacognitive Self-Regulation. Innovative Higher Education, 2006. 30(5): p. 361-375.

2. Costabile, A., et al., Metacognitive Components of Student’s Difficulties in the First Year of University. International Journal of Higher Education, 2013. 2(4): p. 165-171.

3. Roediger III, H.L. and J.D. Karpicke, Test-Enhanced Learning: Taking Memory Tests Improves Long-Term Retention. Psychological Science, 2006. 17(3): p. 249 – 255.

4. El Saadawi, G.M., et al., Factors Affecting Felling-of-Knowing in a Medical Intelligent Tutoring System: the Role of Immediate Feedback as a Metacognitive Scaffold. Advances in Health Science Education, 2010. 15: p. 9-30.