by Mary L. Hebert, PhD; Director, Regional Center for Learning Disabilities; Fairleigh Dickinson University

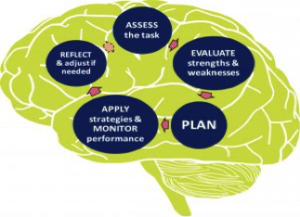

In preparing students for the college transition, it behooves them to reflect on the differences between high school and college. Important considerations for reflection include questions related to the difference of the pace and volume of work, and the degree of independence required for that work. Students with learning differences are statistically more at risk of challenge and adjustment issues and consequently the incompletion of college. The more metacognitively they enter their new academic environment, the greater the likelihood they will be prepared, build upon their self-efficacy and self-advocacy. Using metacognition as a tool to pause, reflect, and pivot accordingly has the potential to optimize capacity to adapt and adjust to the context of one’s learning environment.

Making Time Tangible

Executive function issues can have a significant impact on college students. Many factors can contribute to this. For students who have a learning disability, high co-morbidity rates are noted in the literature (Mohammadi et al., 2019). The executive function skill sets are some of the most critical to manage the rigor and independence of the adult learning experience. A student learning in an adult context are often adjusting to a living and learning environment on a college campus for the first time. Common symptoms of executive function challenges include a distorted sense of time, procrastination, difficulty engaging and disengaging in tasks, and cognitive shifts in task management. The more tangible and observable time can be made, the greater the likelihood of manipulating time and advantageously managing it towards the achievement of one’s immediate, short term and longer term goals.

It takes a synthesis of academic, social, and emotional skill sets to operate collaboratively during a time of transition. In work with new students, it is prudent to encourage and sharpen metacognitive reflection on the process of recognizing time as something that is tangible and malleable and now on the student to manipulate accordingly to accommodate their new adult learning environment. Enriched self-awareness of one’s challenges as well as strengths in regard to executive function, has the potential to support enriched self-competence. Both are cornerstones for success.

Reflect and plan: tackle time management, don’t let it tackle you!

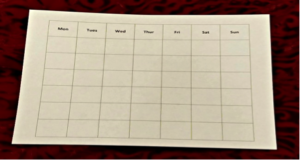

One of the metacognitive tasks that a supportive adult can encourage when a student prepares for the college transition is to create a weekly schedule with their courses listed on the schedule. Likely, the student will observe that there is far more white space than ‘ink on the page’ or black space. I tell the student that I am far less concerned about the ink on the page. Why they ask? Because the ink on the page very nicely identifies where they have to be, for what and with whom. I ask students what they notice about their schedule in comparison to their high school schedule, which is often structured from 7:00 am until 3:00 pm, or even later, given extracurricular commitments and homework. Next, I ask students to identify and list not only academic commitments but study time, wellness hygiene tasks (eating, sleeping, doctor’s appointments, exercise), social time, and other responsibilities and suggest plotting how many hours these will take during the 24 hours day.

It becomes evident during this task that college success is highly dependent on the use of the white space. Academic coaching has become a popular and sought out experience. In fact, embracing a coaching experience correlates with a higher GPA, retention and success for students (Capstick et al. 2019). While academic coaching has the potential to offset executive function challenges and is excellent to have available, ultimately the goal is internalization of metacognitive skills that support more independent and effective executive function. Consequently, the coaching model should focus on internalization as the goal.

Executive function skills are essential to sustain motivation and support perseverance in academics, particularly for students with a learning difference. If executive function skills are challenged and the student does not possess adequate focus, stamina, and organization, there is potential for impact on academic performance. This can increase risk for poor grades and low self-efficacy, and have the potential to compromise the completion of academic tasks. Metacognition facilitates success through promoting self-awareness of one’s executive skill profile of strengths and challenges, and then using that awareness to promote self-monitoring and checking in on one’s task management.

Making time tangible is a powerful strategy in managing executive function symptoms. Metacognitive reflection of the college schedule is a power-tool to support college students who now are in the driver’s seat of managing time rather than being a passenger with others who have managed it for them. The internalization of this skill will be essential to the successful navigation of the ‘white space.’

This added layer of independence and competence will lead to a position of empowerment in the transition to college and be a skill set necessary for career readiness.

References

Capstick, M.K., Harrell-Williams, L.M., Cockrum, C.D. et al. Exploring the Effectiveness of Academic Coaching for Academically At-Risk College Students. Innov High Educ 44, 219–231 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-019-9459-1

Mohammadi M-R, Zarafshan H, Khaleghi A, et al. Prevalence of ADHD and Its Comorbidities in a Population-Based Sample. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2021;25(8):1058-1067. doi:10.1177/1087054719886372