by Dr. Anne Gatling, Associate Professor, Chair Education Department, Merrimack College

(Post #4 Integrating Metacognition into Practice Across Campus, Guest Editor Series Edited by Dr. Sarah Benes)

On the first day of class, I greet my new students with “get to know you” games before walking them through the outline of the semester. I am a science educator and my students are either juniors or graduate students preparing to teach early childhood and elementary education majors.

The last assignment I share with my students is a tree study. Out of all of my assignments, the tree study assignment captures their attention in very different ways. Students often say: “Observe a ‘what’, for the whole semester?” They ponder this for a while. I reply, “Yes, observe a tree, any tree, at least once a month for the whole semester.”

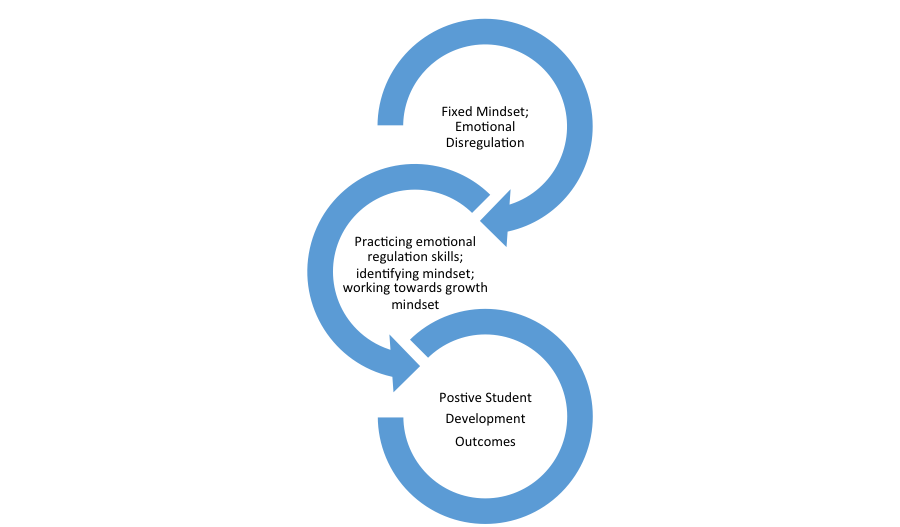

You may be wondering what the connection is to metacognition with this assignment. I view the tree study as a “stepping stone” toward building metacognitive skills. Students develop self-awareness and mindfulness, which can both contribute to metacognition. It can be helpful to have multiple “entry points” for students when it comes to developing metacognition and metacognitive skills. While this may be a more “indirect” path, it can be beneficial to address self-awareness and mindfulness on their own and recognize the potential benefits for metacognition as well.

Tree Study Overview

Each month, for this assignment all they need to do is make a prediction of their tree and an additional new task along the way, such as sketch your tree, observe little signs of critters, and/or work to identify it. Little did I know that this assignment would become much more than a simple observation. Yes, the students became aware of their surroundings through the observation of the trees, more in tune with the process of observing how things change over time, but more importantly I see my students becoming more and more aware of themselves and their environment.

Here is an example of one students’ tree sketch.

This assignment is much different than my other assignments in that I don’t require much more than them taking a picture of their adopted tree once a month and making a few general observations and predictions. I try to meet the students where they are. Some dive in and some just skip around with minimal observations. It is ok. There are far too many things that are high stakes, I just let this one be. I honestly have come to a point where I don’t even want to give this assignment a grade.

What have I learned?

However, I didn’t always have this perspective about the assignment. Initially, this assignment was to help students experience a long-term biology observation, closely investigating changes in a tree, identification, tree rubbings, height etc. But over the years I have come to discover that this assignment means so much more to the students, especially now with quarantines etc.

While I initially didn’t think of this assignment in this way, I have come to realize that these students were also building an awareness of how much of their lives aren’t in the moment and are just beginning to build skills to find their place in the world. This has the potential to help them with their emotional regulation and mindfulness.

More recently I have come to realize that these students were also building an awareness of how much they weren’t in the moment and are beginning to build skills to find their place in the world. This has the potential to help them with their emotional regulation and mindfulness.

While I enjoy seeing their tree pictures, sketches and observations throughout the semester, I have come to love their final reflections. Students each find their own way with the assignment, learning patience in waiting for a new bud, or reaching to touch a tree for the first time. Many students mention becoming more aware of, and appreciating, nature and their surroundings and becoming more aware of small changes. As I consider metacognition and its role in this assignment, I see it as a type of proto-metacognition activity.

Student Outcomes

This process of long-term observation has many students learning the importance of patience. Either their tree sprouted much later than others or their predictions missed the mark. Many students become more aware of and gain an appreciation for the subtle changes as well. “I would never have paid any attention to the trees or thought about doing this if it were not for this assignment. I was able to observe how quickly the tree changes and how crazy it is how the trees just do that on their own.”

One student named her tree and a few students even got their friends involved in making observations. Some were able to spy critters they never knew visited their trees via tracks, and even direct observation. Many students mention looking forward to continuing to observe their tree to see how it continues to grow and change and think of a variety of ways to bring a similar type of study to their future students.

In the beginning, I set more expectations, and not every student saw such value in the assignment. Yet, over time I have learned where to give and where to let go and students seem more ready to see where this experience takes them. This final tree study reflection gives students an opportunity to consider how this tree study impacted them and their learning.

Some students have even found a deeper connection to this assignment. One student, a graduate student placed in a challenging classroom, said, “You go about your day-to-day life and never notice the intricate details that nature undergoes during the springtime. Overall, I think that this assignment forced me to take a second and look at the things that surround me every day. I had never really noticed the tree across the street. . . I like that I got to look closer at the things around me and just take a second. I love trees when I am hiking and sometimes feel like I can only get it then, but this assignment showed me that it is right out my front door always.”

Students, especially now since Covid, seem to be making more changes in how they are looking, slowing down in their process of observation. Maybe by developing more self-awareness and a deeper awareness of their surroundings this assignment can contribute to metacognition perhaps in a more indirect way, offering my students different entry points to the field.

I just assigned the fall tree study this week. I will check in each week and yesterday took them to visit the school garden. There I welcomed them to taste some of its bounty and relax in the peaceful lawn under the trees. Just take time.

In closing, I feel one undergraduate truly embraced this experience in her final project. She placed this poem just above her final tree illustration slide.

Here I sit beneath a tree,

Heartbeat strong,

My soul hums free.

Angie Weiland Crosby

A special thank you to Marcia Edson and Jeff Mehigan for their design of the initial tree study.