by Dr. Ed Nuhfer, California State Universities (retired)

Hmmm… COVID year… what a trip. If I slept through it, there were nightmares—lots of ’em. Where did I leave off last April (Nuhfer, 2020)? Oh yeah, we ended with a question: “How might teaching students to write their learning philosophies improve their learning?” Well, OK…let’s continue that… by first realizing that professors’ teaching philosophies are their learning philosophies, and those who do write them come to recognize how keeping such a written record enhances success in teaching.

Philosophies are reflective; they record the results of a metacognitive conversation with oneself. The results articulate the plan for practice disclosing what one wants to do, how one chooses to do it, and how to know the chosen practices’ impact. Philosophies focus on learning about process, which is too rarely the stuff of college education, where the emphasis is on learning content—the disciplines’ products. Even “student-centered-learning” structures too seldom involve directly teaching students to be reflective about how to learn.

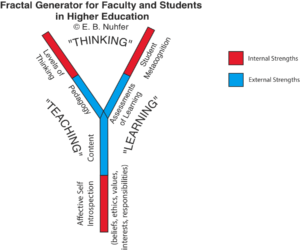

Six critical components of a teaching philosophy appeared in the graphic of the fractal generator above (and also shared my April 2020 blog). An informed teaching/learning philosophy considers all six components. Three crucial components describe internal strengths enlisted during learning: affect, levels of thinking, and metacognition, and three more are competencies mainly built from external sources: content, pedagogy, and assessment.

For nearly twenty years, I led week-long faculty development retreats in which each faculty arrived with a written one-page document that they had constructed as their teaching philosophy. A faculty member rarely arrived at a retreat with a written philosophy that addressed more than three of the six components.

Through the retreats, participants revisited and edited their philosophy a bit each day. Our final exercise of the retreat was sharing the revised philosophies in groups and polishing them more for use. No participant left without awareness of the vital role that each of the six components played. Participants’ written philosophies of practice were probably their most valuable tangible takeaway.

Why written philosophies?

Consider the advantage a written plan confers to constructing anything complex. Architectural design requires written blueprints and strategies because the challenge is just too complex to address well by acting spontaneously from what one can carry around in one’s head. Construction contractors avoid working without a written plan because doing so produces disappointing results.

Learning and teaching are challenges as complex as any construction project. A teaching/learning philosophy acts as the equivalent of an architectural design plan and encompasses the big picture of what we intend to do. Students need learning philosophies for the same reason professors need them, but acting spontaneously without any written philosophy is probably the norm in higher education. How many of your students approach learning with a written plan?

The six components that are so essential for professors to consider also confer similar value to students. It really is up to professors to mentor students to craft their first informed learning philosophies. An excellent way to start students toward constructing their personal learning philosophies is to give each a nearly blank paper with the six components’ names at the top.

Beginners must begin to incorporate the six as a checklist by asking self: “Where are awareness of affect, levels of thinking, etc. in my practice?” After they internalize these six through at least a year of practice, they become cognizant of how all six are interconnected, and awareness occurs that developing one component awakens new insights about the others’ roles. Some authors of philosophies later employ visualization and supplement their philosophies with graphics.

Years ago, the fractal generator shown above became my graphical philosophy. I produced fifty articles under the title “Educating in Fractal Patterns…” for The National Teaching and Learning Forum, as that graphic philosophy helped me more deeply understand and grow from my experiences. Those who maintain a written philosophy and reflect on it regularly will almost surely have similar “Aha moments.”

Essential Components

Let’s see how we can help students become reflective and increase their capacity to learn from the six components.

Affect

We can help students to appreciate the importance of affect by reflecting upon whether the affective mode in which they find themselves is “I have to do this” or “I want to do this.” (See assignment shared in Nuhfer 2014.) Wanting to learn enlists more brainpower to drive learning. Finding ways to make learning fun for ourselves, to want to do it—such as making a party of it by studying with others, can become our most valuable asset. Quantitative courses elicit the most negative affective responses from students (Uttl, White, Morin, 2013). Yet, the book I recommend as the most inspirational book ever written to learn to reverse negative feelings for specific content is Francis Su’s Mathematics for Human Flourishing. A particular quote I like from p. 11 follows: “When some people ask, ‘When am I ever going to use this?’ what they are really asking is ‘When am I ever going to value this?‘”

Pedagogy

Teachers employ “active learning” pedagogies (Univ Wyoming resources) to increase learning through engagement. One principle underlies all “active learning:” the more of the brain invoked during learning, the better the learning. But another principle is seldom addressed: the longer the time spent in learning with significant portions of the brain activated, the greater the understanding.

Students can apply the same principles to enlist more of their brains. Writing to learn along with reading invokes more of the brain than only reading to learn. Revision of written products, multiple revisions, is one of the most powerful learning strategies known, at least as powerful as any modality on the “Active Learning Spectrum” linked above. For developing their learning philosophies, instructors should assign students to write, revise, and record at the end of each revision how doing revision improved their understanding. Learning to enlist active learning by writing to learn for oneself does not require doing a thesis. Simply writing and revising how to solve a word problem or an evaluative assignment offers sufficient capital through which to develop an appreciation for the power of writing to learn.

Content

Writing (Didn’t we just mention its power?) a knowledge survey builds understanding of the course content that faculty quickly appreciate (Nuhfer & Knipp, 2003). Watch these two very short videos to get a sense of what knowledge surveys are and their impact.

With each knowledge survey item that a professor writes, they should follow that with the thought, “What do students need to know to respond with understanding?” That will lead to writing several additional items to build the scaffold needed to address the former item. While students lack the expertise to construct course-based knowledge surveys from scratch, instructors can direct students to share in scaffolding their learning. They can let students build a knowledge survey in small pieces by frequent assignments such as: “Given the content we covered today, replace the knowledge survey’s items about that content with your own authored items to address the equivalent content.” An additional brief helpful exercise to help students to build their own learning philosophy can be: “How did writing your own knowledge survey items change your understanding of the content material? Why might writing such items be a useful learning strategy for learning in other subjects and courses?”

Levels of Thinking

We have already covered developmental levels in a prior post (Nuhfer, 2014), and we showed the connection between levels of thinking and affect (Nuhfer, 2018). Nearly all students misperceive becoming educated as learning skills and content. They have heard of “critical thinking” or “higher-order thinking,” but almost none can really articulate what either looks like. They will not know about such developmental levels of thinking unless the faculty teach them. We earlier provided a module with which instructors can do so (Nuhfer & Bhavsar, 2014). If you are unfamiliar with such developmental models and levels of thinking, which is likely, go through the same module for yourself. Then, guide students through it.

Metacognition

Is it surprising that this component should receive a mention on this blog? What would be truly surprising is if any personal learning philosophy sentence was not a product of metacognitive reflection. A written philosophy archives the portions its writer valued that came out of purposefully directed conversations with self. It expresses the current state of the author’s focus at a specific stage of development. It will change with additional experiences and reflections.

Assessment

The assessment portion of the philosophy likely considers three questions. The first is “Did I really practice my philosophy—did I do what I planned to do?” The second is “What happened as a result?” The third is “Based on what I learned from what happened, what will I focus on next?”

When one develops the ability for “fractal thinking,” one is constantly considering what would result if a pattern of action taken at one scale were enacted at different scales. If these three assessment queries give valuable substance to building an individual’s expertise, what might result if we nurtured such happening at the scale of a program or an institution?

For years, I had hoped to convince an institution to replace the practice of using student ratings scores as the highest stakes criterion for the annual review of instructors with professors’ written philosophies instead. Review committees would examine each philosophy and ask correlatives to the three questions above. It seems easy to see why encouraging metacognitive reflection on improving practice offers a superior option to thinking instead of raising student ratings’ scores. Sigh! I’m still hoping for just one institution to try it.

In summary, writing, revisiting, and revising learning philosophies scaffold us to higher proficiency. Addressing the same six components offers professors and students common ground on which to come together to understand learning and the process of becoming educated.