By Yianna Vovides, PhD (Series Editor), Georgetown University

I once worked with a faculty member who was skeptical about teaching an online course, let alone spending time working with a designer on it. So, after my first meeting with him, realizing his hesitations, I created a prototype based on his course syllabus to show him what was possible. I remember him saying, I couldn’t see how to teach my course online, I am not a techie, but maybe I can if you help me.

He now saw me as his coach and partner, helping him plan how to engage students, helping him put in place assignments that he could manage within the course management system, helping him during his teaching. All along, during the four months we spent on his course, I would ask him about his teaching philosophy and his approach to teaching in his discipline. About a month before the course was ready to launch, I asked him if he could write a few paragraphs to explain to his students what he was sharing with me about his choices in the readings, his expectations in relation to how students approached a text and what he looked for in their assignments. He did.

We ended up recording these (only audio) and adding them to his week-by-week course structure. I then asked him if he was up for doing some more recording that focused on the selection of texts in his courses. I asked him to share his study of the authors themselves. He did. I then created an e-book that students would use to explore a bit more about the authors from their instructor’s perspective.

When the course opened, I spent an hour on the phone walking him through how to respond to student posts in the discussion board. He said, Thank you, I think I can do this! And he did. During the first run of his course, I sent him weekly emails to check in and point out the student monitoring/analytic features for making sure his students were keeping up.

What does metacognition have to do with it?

Because the process of online course development takes time, the relationship between the designer and the faculty tends to result in one that lasts past that one course experience. It is usually after the first course design and the first time faculty teach their course when they realize how much they learned about teaching and learning. They then go on to adapt their other courses. They are more metacognitively aware. They are aware of their own approaches to teaching and learning, aware of what it takes to design and teach a course in another mode, and are aware that good design and teaching involves planning, monitoring, reflecting, evaluating, and adapting existing practices. This is how I define the process of course adaptation that we will explore further in this post.

Let us dig a bit deeper into course adaptation.

In this post, I describe the adaptive approach we have implemented as part of our online programs efforts at the Center for New Designs in Learning and Scholarship (CNDLS), Georgetown University. The approach connects instructional design practices with a faculty development focus that encourages metacognition (planning, monitoring, evaluating). I started with the following overarching question: How should instructional designers guide faculty to rethink their approach to course design to follow an adaptive faculty development process? I then identified the following sub-questions that formed the basis of the approach and operationalizing the process:

- What techniques can instructional designers follow to engage faculty in design thinking?

- What techniques can instructional designers follow to engage faculty in meta reflections about their teaching methods?

- How can instructional designers use learning analytics to help faculty continue engaging in meta reflections during their online teaching?

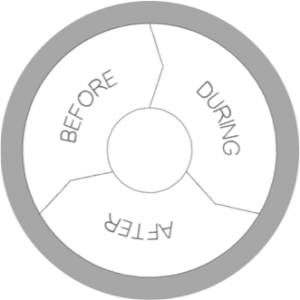

The questions I listed above offered the CNDLS online programs team a way to problematize our approach to design. I realized that we needed to make visible the levels (macro, meso, micro) that we address during the design process and enable faculty to navigate these successfully. We implemented a model that enables conversations about design and development at all levels by following a before, during, after approach (see Figure 1).

The guiding questions start at the course level and move to sessions and sequence of engagement exploring the teaching and learning experience across time. These questions include but are not limited to the following:

- Tell us about your course. What do you love about this course? What do you think the students love about this course?

- What are the things that you think about when you prepare to teach this course?

- How do you engage your students before the semester starts?

- What do you do during that first class session?

- What do you expect students to do during the first class session?

- What do you do after the class session?

- What do you want students to do after the class session?

These questions help faculty reflect about their approach to teaching and learning. By asking these questions up front and throughout the course adaptation process we are embedding metacognitive instruction within the course design model itself. In addition, throughout the design process we include check-in sessions that allow both the designer and faculty to pause and ask:

- Is our design plan still valid?

- Is our choice of technology going to support students in their learning process?

- Do we need to do anything differently?

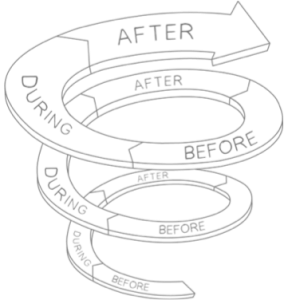

What these check-in questions do over the span of four to six months of engaging with an individual faculty on the course design and development process is that the conversations become connected across time and merge into a spiral design model. Figure 2 visualizes the spiral model that supports the faculty development approach that instructional designers take. Once faculty members experience this model, they continue to follow this design approach as they envision their other courses. In addition, they tend to re-visit their approach to their teaching shifting from an instructor-centered to a student-centered approach.

Because the model is based on time, it easily communicates across the various disciplines. What do I mean by that? Because the conversations that surround this model are related to teaching practices, it is also a way to account for contact time (faculty-student interaction) and learning time (student effort). We refer to the combination of contact time and learning time as instructional time in conversations with faculty. In remote teaching and learning, instructional time is an entry point to envisioning how learning can happen in different ways.

The rest of the mini-series on Learning. Design. Analytics. includes examples using this approach that highlight strategies used to activate metacognitive awareness during the course design and re-design process through the designer-faculty interaction. In addition, the series highlights how technology interventions and learning analytics are integrated as part of the process.

Some background about instructional design and online education to frame the approach

Adapting traditional classroom-based courses to online may sound simple given that online education has been around for more than two decades. In fact, instructional design, a field of study that is over 80 years old, offers theories, models, and processes that guide designers to make this adaptation from traditional classroom-based teaching to online. This is a technical challenge – solutions are available and are knowable. However, in higher education, the instructional design process, when framed to support faculty development, introduces complexity. The challenge is no longer technical because the focus of the challenge is no longer about the course adaptation from traditional to online but the people involved in making the adaptation happen (faculty, designers, media specialists, students, and other members of the team that supports this process). It is a process of transformation.

Let us pull this apart a bit more. Higher education as an institution has been described as lacking innovation and flexibility for promoting impactful teaching and learning (Rooney et al., 2006). That was in 2006. Between 2006 and 2016, we have seen online education grow and thrive with over 6 million students (approximately 30% of all higher education students) enrolled in at least one distance education course in the United States (Allen & Seaman, 2017). Then COVID-19 happened. Remote teaching and learning is happening across the globe and is now the new normal. Given the speed of the changes, some schools have been able to pivot and put in place the needed support for their instructors while others are struggling to determine what that support needs to be and how to operationalize it.

There are many factors that contribute to these decisions besides resources such as institutional, departmental, and individual cultural norms. For example, the institutional culture may be known by those who are in it but much of it is hidden from those new to it which may lead to actions that are oftentimes driven by assumptions rather than visible evidence (Halupa, 2019). Many academic departments tend to value individual contributions and can propagate a competitive rather than a collaborative environment. This may then lead to a less cohesive curriculum online. Individual faculty members are experts in their discipline but not necessarily in the discipline of teaching and learning. Therefore, within this complex network of needs, faculty development efforts in higher education try to balance group and individual engagements to provide opportunities for faculty to get the support they need in their teaching.

Recognizing that there are different instructional development needs necessitates that we offer different entry points and pathways in our faculty development programming. Within the online course design efforts, we work with faculty to help them see their teaching challenge from a design thinking perspective that begins with an exploration of what individual learners will experience. By doing so, we are no longer facing a technical challenge but rather an adaptive one because we are now focusing on individual learner needs. To tackle this adaptive challenge that is implicitly dynamic because of the focus on humans, we argue that the approach requires that planning, monitoring, and evaluation become an integral part of the process at both the cognitive and metacognitive levels.

References

Allen, I. E., & Seaman, J. (2017). Digital Compass Learning: Distance Education Enrollment Report 2017. Babson survey research group.

Halupa, C. (2019). Differentiation of Roles: Instructional Designers and Faculty in the Creation of Online Courses. International Journal of Higher Education, 8(1), 55-68.

Rooney, P., Hussar, W., Planty, M., Choy, S., Hampden-Thompson, G., Provasnik, S., & Fox, M. A. (2006). The Condition of Education, 2006. NCES 2006-071. National Center for Education Statistics.