by Brody Becker, Jack Curry, Charlie Gorman, Caleb Norris, J. Michael Rifenburg, and Erik Siegele

We offer an assignment from a general education writing class that invites students to hone their metacognitive knowledge by, oddly enough, writing about writing. Before we turn to this assignment, we need to detail who we are. We are a six-person author team. Five of us are first-year U.S. Army cadets. All five plan to commission into the U.S. Army following graduation. One of us is a civilian, tenured professor in the English Department.

During the Fall 2021 semester, we met in English 1102, a general education writing class offered at the University of North Georgia (UNG). Our university is a federally designated senior military college, like Texas A&M and The Citadel, tasked with educating future U.S. Army officers. Civilians also attend UNG. At our school, roughly 700 cadets learn alongside roughly 20,000 civilian undergraduate students. These details are important to what we want to describe in this post: not only a metacognitive writing assignment for this specific class but also the perspective of cadets who completed this assignment and the value of such metacognitive work for cadets. We write as a six-person team and offer collective ideas (as we do in this paragraph). However, we also value individual perspective. Author order is alphabetical and does not signal one writer contributing more than another writer.

During the Fall 2021 semester, we met in English 1102, a general education writing class offered at the University of North Georgia (UNG). Our university is a federally designated senior military college, like Texas A&M and The Citadel, tasked with educating future U.S. Army officers. Civilians also attend UNG. At our school, roughly 700 cadets learn alongside roughly 20,000 civilian undergraduate students. These details are important to what we want to describe in this post: not only a metacognitive writing assignment for this specific class but also the perspective of cadets who completed this assignment and the value of such metacognitive work for cadets. We write as a six-person team and offer collective ideas (as we do in this paragraph). However, we also value individual perspective. Author order is alphabetical and does not signal one writer contributing more than another writer.

An Overview of this Metacognitive Assignment

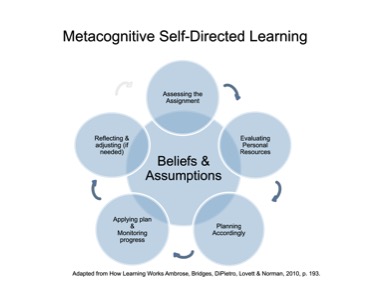

I (Michael) regularly teach this general education writing class. One writing assignment opened with the following prompt: “For this second paper, I invite you to reflect on a previous paper you wrote during your college or high school career. Through detailing when and where you wrote the paper, the processes you undertook to write the paper, and the feedback or grade you received on this paper, you will make a broader argument about the importance of reflecting back on writing and lessons one learns from undertaking such reflection.” This assignment is a modified version of a similar writing assignment in Wardle and Downs’s (2014) popular textbook Writing About Writing.

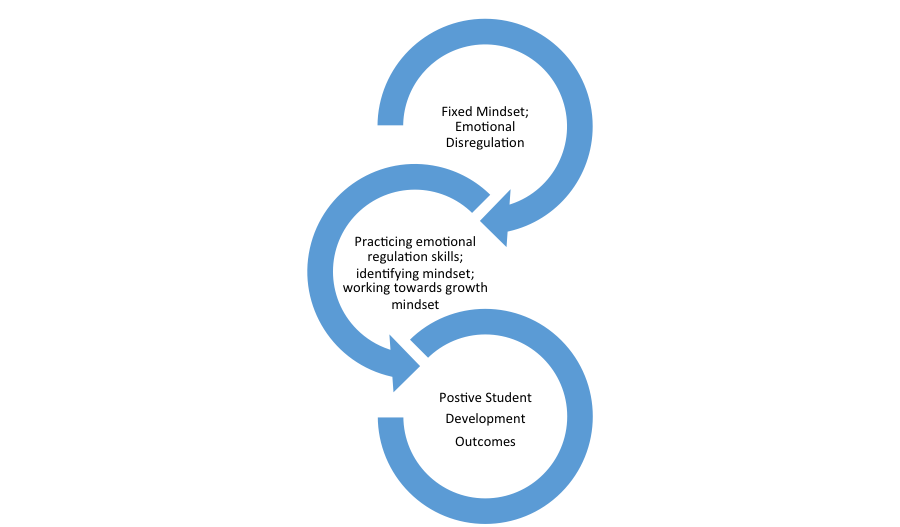

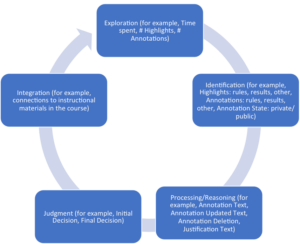

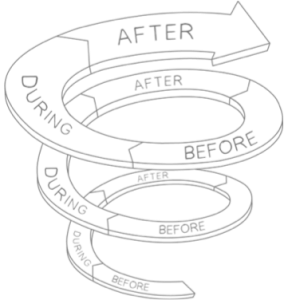

To prepare to write this paper, we read the “Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing,” a national consensus document outlining, as the title suggests, a framework for students to succeed at college level writing. This document offers eight habits of mind essential for student-writers to hone: one of these habits of mind is metacognition. We also read through portions of Tanner’s (2017) “Promoting Student Metacognition.” Tanner provided a table of metacognitive questions instructors can ask students before, during, and after the course.

Students then wrote a 1,500 word essay in response to this assignment. All student co-authors for this blog post enrolled in this specific class and completed this assignment. I now turn to my co-authors, cadet Charlie Gorman and cadet Brody Becker, to hear their perspectives on this assignment.

Cadets’ Reflections

Charlie’s reflection on this metacognitive assignment

I found that this assignment was beneficial to grow as a writer. Reflecting back on activities or assignments is a great way to improve in any aspect of life. I would have never thought about writing a paper about a paper until I was given the opportunity to write this assignment. As a future leader in the military, my writing will consist of educating material, reports, and special directions. Completing this assignment has set me up and taught me how to use past failures and successes to improve upon a future performance.

Brody’s reflection on this metacognitive assignment

This paper on metacognition was difficult for me because I had never done anything along these lines in a writing aspect previously. However, I soon found it to be helpful because of all the things I could learn from and look for in future writing. I had never thought about how looking back at previous writing could be helpful to me, so I always disregarded any past assignments and never thought about them again. This was a teaching moment for me, and I always take chances to learn new things. This assignment was one of the more beneficial things that I have done that I will continue to use for future assignments and will carry over to other things in life.

Why such an assignment is particularly helpful for cadets

In this section, Cadet Jack Curry considers why such a metacognitive writing assignment is particularly helpful for cadets who, after graduation, will commission as officers in the U.S. Army.

As a cadet, metacognition is an important step for our future progress. Being able to review and learn from our mistakes and our successes, helps us become better leaders. After any exercise or training, we conduct After Action Reviews (AARs) to find out how we can either improve upon or continue upon our training. As future officers, our job is to continue improving the skills we will use to lead future soldiers. The U.S. Army’s publication Training Circular 25-20: A Leader’s Guide to After Action Reviews (1993), states “the reason we conduct AARs are in order to find candid insights into specific soldier, leader, and unit strengths and weaknesses from various perspectives, and to find feedback and insight critical to battle-focused training.”

Concluding words of hope for more faculty-student partnerships

Our partnership started as a teacher-student one. Michael designed writing assignments and led classroom activities, and Charlie, Caleb, Jack, Brody, and Erik completed writing assignments and completed classroom activities. Near the end of the semester, our partnership shifted into one of co-authors where we wrote this blog post together over Google Docs, bounced ideas back and forth in-person after class, and coordinated further over email. We use the noun partnership intentionally to signal our commitment to pedagogical partnerships, an international and interdisciplinary movement to re-see the student-faculty relationship as one in which both serve as active agents in curriculum design, implementation, and assessment (e.g., Cook-Sather et al., 2019). As readers of and contributors to Improve with Metacognition continue to explore the benefits of structured metacognitive tasks throughout higher education, we hope that undergraduate students are at the forefront of this exploration. Partnerships between faculty and students are one productive step to ensuring that our classroom practices and processes best serve all our students.

References

Cook-Sather, A., Bahti, M., & Ntem, A. (2019). Pedagogical partnerships: A how-to guide for faculty, students, and academic developers in higher education. Elon University’s Center for Engaged Learning Open Access Book Series. Retrieved from https://www.centerforengagedlearning.org/books/pedagogical-partnerships/

Council of Writing Program Administrators et al. (2011). “Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing.” Retrieved from http://wpacouncil.org/files/framework-for-success-postsecondary-writing.pdf.

U.S. Department of the Army. (1993). Training Circular 25-20: A Leader’s Guide to After Action Reviews. Army Publishing Directorate. Retrieved from https://armypubs.army.mil/productmaps/pubform/details.aspx?pub_id=71643

Tanner, K. (2017). Promoting student metacognition. Life Sciences Education, 11(2). Retrieved from https://www.lifescied.org/doi/full/10.1187/cbe.12-03-0033

Wardle, E., & Downs, D. (2014). Writing About Writing: A College Reader. 2nd ed. Bedford.