By: Melissa Terlecki, PhD, Cabrini University PA

Background

Measuring metacognition, or the awareness of one’s thoughts, is no easy task. Self-report may be limited and we may overestimate the frequency with which we use that information to self-regulate. However, in my quest to assess metacognition, I found the MAI, or the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (Schraw and Dennison, 1994). The MAI, comparatively speaking, is one of the most widely used instruments. Schraw and Dennison found an alpha coefficient of .91 on each factor of the MAI and .95 for the entire MAI, which indicates reliability. Pintrich (2000) agrees the MAI has external validity given MAI scores and students’ academic achievement are highly correlated.

The Problem

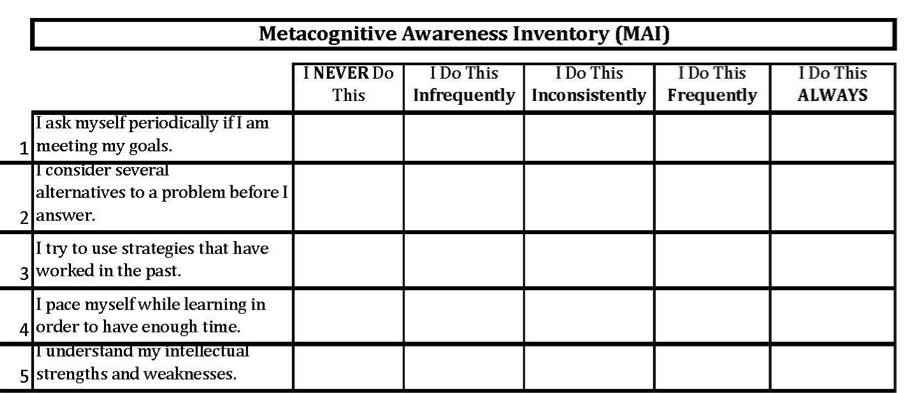

Despite the wide use and application of the MAI, I found the survey measurement scale unfitting and constrictive. The survey consists of 52 questions with true or false response options. Some of the behaviors and cognitions measured on the MAI include, “I consider several alternatives to a problem before I answer,” “I understand my intellectual strengths and weaknesses,” “I have control over how well I learn,” and “I change strategies when I fail to understand”, just to name a few (see https://services.viu.ca/sites/default/files/metacognitive-awareness-inventory.pdf).

Though these questions are valid, to dichotomously respond to an extreme “true”, as in I always do this, OR a “false”, as in I never do this, is problematic. Yes-No responses also make for difficult quantitative analysis. All or nothing responses makes hypothesis testing (non-parametric testing) challenging. I felt that if the scale was changed to be Likert-type, then participants could more accurately self-report on how often they may exhibit these behaviors or cognitions, and we could more readily assess variability and change.

The Revised MAI

Thus, I revised the MAI to use a five-point Likert-type rating scale, ranging from “I never do this” to “I do this always” (see Figure 1). Five points also allows a middle rating with two extremes on either side (always/never). It is important to note that the original content of the survey questions has not been altered.

My recent findings (Terlecki & McMahon, 2018; Terlecki & Oluwademilade, in preparation) show the revised MAI to be effective as a pre- and post-test measure to assess the growth due to metacognitive instruction, compared to controls with varying levels of instruction, in college students.

Figure 1. Revised MAI likert-scale (Terlecki & McMahon, 2018). Response scale adapted from Schraw and Dennison (1994) with permission from Sperling (Dennison).

In our longitudinal sample of roughly 500 students, results showed that students exposed to direct metacognitive instruction (across a one semester term) yielded the greatest improvements on the revised MAI (compared to controls), although maturation (age and level in school) had a moderating effect. Thus, we concluded that students who were deliberately taught metacognitive strategies did exhibit an increase in their cognitive awareness, as measured by the revised MAI, regardless of initial levels of self-awareness. In other words, the older one is, the greater the likelihood one may be self-aware; however, explicit metacognitive intervention still boasts improvements.

These changes might not have been elucidated using the original, dichotomous true/false response options. The revised MAI is a useful tool in measuring such metacognitive behaviors and whether changes in frequency may occur over time or intervention. Likewise, anecdotal evidence from my participants, as well as researchers, supports the ease of reporting using this Likert-scale, in comparison to the frustration of using the 2-point bifurcation. Still, usage of the revised MAI in more studies will be required to validate.

Suggestions for Future Usage of the MAI & Call for Collaboration

The Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (MAI) is a common assessment used to measure metacognition. Quantifying metacognition proves challenging, yet this revised instrument appears promising and has already provided evidence that metacognition can grow over time. The addition of a wider range of response options should be more useful in drilling down to frequency of usage of metacognitive behaviors and thinking.

Validation studies on the revised scoring have yet to be conducted, thus if other researchers and/or authors are interested in piloting the revised MAI, please contact me (* see contact information below). It would be great to collaborate and collect more data using the Likert-form, as well as have a larger sample that would allow us to run more advanced statistics on the reliability and validity of the new scaling.

References

Pintrich, P.R. (2000). Issues in self-regulation theory and research. Journal of Mind and Behavior, 21, 213-220.

Schraw, G., & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 19(4), 460-475.

Terlecki, M. & McMahon, A. (2018). A call for metacognitive intervention: Improvements due to curricular programming and training. Journal of Leadership Education, 17(4), doi:10.12806/V17/I4/R8

Terlecki, M. & Oluwademilade, A. (2020). The effects of instruction and maturity on metacognition (in preparation).

*Contact: If looking to collaborate or validate the revised instrument, please contact Melissa Terlecki at mst723@cabrini.edu.

If you’d like to compare the MAI to other metacognition assessment inventories, please see “A Non-Exhaustive List of Quantitative Tools to Assess Metacognition” by Jessica Santangelo.