by Patrick Cunningham, Ph.D., Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology

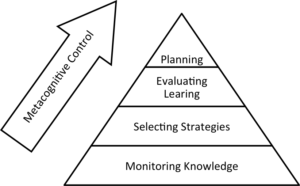

Metacognition involves monitoring and controlling one’s learning and learning processes, which are vital for skillful learning. In line with this, Tobias and Everson (2009) detail the central role of accurate monitoring in learning effectively and efficiently. Metacognitive monitoring is foundational for metacognitive control through planning for learning, selecting appropriate strategies, and evaluating learning accurately (Tobias & Everson, 2009).

Figure 1 – Hierarchy of metacognitive regulatory processes. Adapted from Tobias and Everson (2009).

Unfortunately, students can be poor judges of their own learning or fail to engage in the judging of their learning and, therefore, often fail to recognize their need for further engagement with material or take inappropriate actions based on inaccurate judgements of learning (Ehrlinger & Shain, 2014; Winne and Nesbit, 2009). If a student inaccurately assesses their level of understanding, they may erroneously spend time with material that is already well known or they may employ ineffective strategies, such as a rehearsal strategy (e.g., flash cards) to build ROTE memory when they really need to implement an elaborative strategy (e.g., explaining the application of concepts to a new situation) to build richer integration with their current knowledge. This poor judgement extends to students’ perceptions of the effectiveness of their learning processes, as noted in the May 14th post by Sabrina Badali, Investigating Students’ Beliefs about Effective Study Strategies[. There Badali found that students were more confident in using massed practice over interleaved practice even though they performed worse with massed practice.

Fortunately, we can help our students to develop more accurate self-monitoring skills. The title question is one of my go-to responses to student claims of knowing in the face of poor performance on an assignment or exam. I introduced it in my April 4th blog post, Where Should I Start with Metacognition? It gently, but directly asks for evidence for knowing. In our work on an NSF grant to develop transferable tools for engaging students in their metacognitive development, my colleagues and I found that students struggle to cite concrete and demonstrable (i.e., objective) evidence for their learning (Cunningham, Matusovich, Hunter, Blackowski, and Bhaduri, 2017). It is important to gently persist. If a student says they “reviewed their notes” or “worked many practice problems,” you can follow up with, “What do you mean by review your notes?” or “Under what conditions were you working the practice problems?” The goal is to learn more about the students’ approach while avoiding making assumptions and helping the student discover any mismatches.

We can also spark monitoring with pedagogies that help students accurately uncover present levels of understanding (Ehrlinger & Shain, 2014). Linda Nilson (2013) provides several good suggestions in her book Creating Self-Regulated Learners. Retrieval practice takes little time and is quite versatile. Over a few minutes a student recalls all that they can about a topic or concept, followed by a short period of review of notes or a section of a book. The whole process can be done individually, or as individual recall followed by pair or group review. Things that are well-known are present with elaborating detail on the list. Less well-known material is present, but in sparse form. Omissions indicate significant gaps in knowledge. The practice is effortful, and students may need encouragement to persist with it.

I have used retrieval practice at the beginning of classes before continuing on with a topic from the previous day. It can also be employed as an end-of-class summary activity. I think the value added is worth the effort. Because of its benefits and compactness, I also encourage students to use retrieval practice as a priming activity before regular homework or study sessions. Using it in class can also lower students’ barriers to using it on their own, because it makes it more familiar and it communicates the value I place on it.

Nilson (2013) also offers “Quick-thinks” and Think Aloud problem -solving. “Quick-thinks” are short lesson breaks and can include “correct the error” in a short piece of work, “compare and contrast”, “reorder the steps”, or other activities. A student can monitor their understanding by comparing to the instructor’s answer or class responses. Think Aloud problem-solving is a pair activity where one student talks through their problem-solving process while the other student listens and provides support, when needed, for example, by prompting the next step or asking a guiding question. Students take turns with the roles. A student’s fluency in solving the problem or providing support indicates deeper learning of the material. If the problem-solving or the support are halting and sparse, then those concepts are less well-known by the student. As my students often study in groups outside of class, I recommend that they have the person struggling with a problem or concept talk through their thinking out loud while the rest of the group provides encouragement and support.

Related to Think Alouds, Chiu and Chi (2014) recommend Explaining to Learn. A fluid explanation with rich descriptions is consistent with deeper understanding. A halting explanation without much detail uncovers a lack of understanding. I have used this in various ways. In one form, I have one half of the class work one problem and the other half work a different problem or a variant of the first. Then I have them form pairs from different groups and explain their solutions to one another. Both students are familiar with the problems, but they have a more detailed experience with one. I also often use this as I help students in class or in my office. I ask them to talk me through their thinking up to the point where they are stuck, and I take the role of the supporter.

The strategies above provide enhancements to student learning in their own right, but they also provide opportunities for metacognitive monitoring – checking their understanding against a standard or seeking objective evidence to gauge their level of understanding. To support these metacognitive outcomes I make sure to explicitly draw students’ attention to the monitoring outcomes when I use pedagogies to support monitoring. I am also transparent about this purpose and encourage students to seek better evidence on their own, so they can truly know what they know.

As you consider adding activities to your course that support accurate self-assessment and monitoring, please see the references for further details. You may also want to check out Dr. Lauren Scharff’s post “Know Cubed” – How do students know if they know what they need to know? In this post Dr. Scharff examines common causes of inaccurate self-assessment and how we might be contributing to it. She also offers strategies we can adopt to support more accurate student self-assessment. Let’s help our student generate credible evidence for knowing the material, so they can make better choices for their learning!

References

Chiu, J. L. & Chi, M. T. H. (2014). Supporting Self-Exlanation in the Classroom. In V. A. Benassi, C. E. Overson, & C. M. Hakala (Eds.). Applying science of learning in education: Infusing psychological science into the curriculum. Retrieved from the Society for the Teaching of Psychology web site: http://teachpsych.org/ebooks/asle2014/index.php

Cunningham, P., & Matusovich, H. M., & Hunter, D. N., & Blackowski, S. A., & Bhaduri, S. (2017), Beginning to Understand Student Indicators of Metacognition. Paper presented at 2017 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Columbus, Ohio. https://peer.asee.org/27820

Ehrlinger, J. & Shain, E. A. (2014). How Accuracy in Students’ Self Perceptions Relates to Success in Learning. In V. A. Benassi, C. E. Overson, & C. M. Hakala (Eds.). Applying science of learning in education: Infusing psychological science into the curriculum. Retrieved from the Society for the Teaching of Psychology web site: http://teachpsych.org/ebooks/asle2014/index.php

Nilson, L. B. (2013). Creating Self-Regulated Learners: Strategies to Strengthen Students’ Self-Awareness and Learning Skills. Stylus Publishing: Sterling, VA.

Tobias, S. & Everson, H. (2009). The Importance of Knowing What You Know: A Knowledge Monitoring Framework for Studying Metacognition in Education. In Hacker, D., Dunlosky, J., & Graesser, A. (Eds.) Handbook of Metacognition in Education. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 107-127.

Winne, P. & Nesbit, J. (2009). Supporting Self-Regulated Learning with Cognitive Tools. In Hacker, D., Dunlosky, J., & Graesser, A. (Eds.) Handbook of Metacognition in Education. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 259-277.