by Dr. Ed Nuhfer, California State Universities (retired)

Since 2002, I’ve written a theme-based column, “Developers’ Diary,” for The National Teaching and Learning Forum (NTLF). The central theme through all of these columns is “educating in fractal patterns.” Additionally, I facilitated week-long retreats from 1993 to 2010, and still run workshops, both of which employ visualization of a fractal generator as an aid to understanding concepts of teaching and learning. The wonderful “LAMP” (Learning Actively Mentoring Program) program at the University of Wyoming, where I serve as a mentor, continues to incorporate this aid in participants’ development of informed teaching philosophies.

In writing involved with our academic professions, perhaps no documents are so much the products of metacognition as our written teaching philosophies. These come from within us, which may account for their being so challenging to write. The information-gathering and evidence-based kinds of education through which we mastered most of our own education rarely gave us much practice for metacognitive self-assessment and deep self-reflection.

When properly used, the value of a teaching philosophy lies in “shaping” and nurturing the continuous growth of its author’s expertise. Rather than just a statement, the document serves to direct the author’s intention to enact the practices espoused in the philosophy. In this column, I seek to infuse readers’ already developed metacognitive capacities with an added dimension of “fractal awareness.”

Fractals: Why “Y” Why?

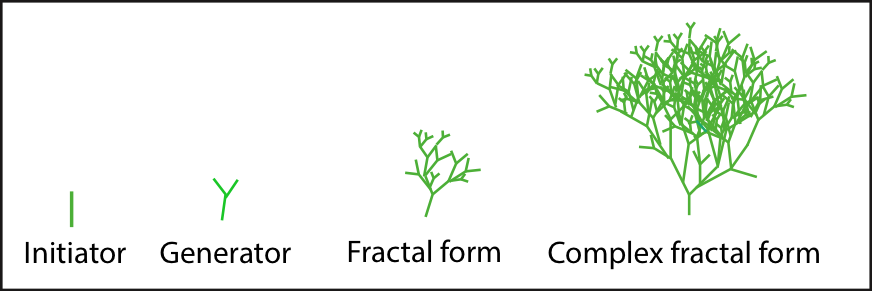

A fractal form is one that develops through growing from a “seed” called a generator (Fig. 1). Development involves repeatedly connecting additional generators to the growing structure. Thus, the character of the full form depends on the characteristics of the generator. A generator consists of simple Euclidean parts, perhaps the simplest being a straight-line segment. We enlist Figure 1 to clarify how initiators form generators, and fractal forms grow through recursively adding more and more generators.

Figure 1. Development of a branching fractal form from a “Y-shaped” generator and its precursor initiator (from Nuhfer, 2007). Fractal shapes are the most common of all natural forms. Plants, mountains, clouds, coastlines, patterns of natural events in time like rainfall and floods, blood vessels, and the neural networks in our brains are examples of natural fractal forms.

The concept of fractal form is more than an abstract visualization that inspires creatively thinking about the process of becoming educated. The neural connections that develop in our brains through learning really are fractal forms. When we learn, we connect and stabilize fractal neural networks, so a good deal of our thinking and behavior almost surely has fractal qualities. We can enhance our understanding of educating and becoming educated by discovering the fractal qualities that these endeavors exhibit. One of the most important to recognize is that healthy final forms grow from robust generators. In practice, we can build a sturdy generator from a “blueprint” established by writing a well-informed teaching philosophy. If we mindfully practice this philosophy, the strengths and omissions of our “generator” grow into the strengths and blind spots that characterize our practice.

The branching fractals that develop in our brains are certainly more complex than the model in Figure 1, but even that simple figure helps us to understand and explain countless aspects of the process of learning and, over time, developing higher level thinking capacities.

The Philosophy as a Fractal Generator for Teaching, Learning, and Thinking

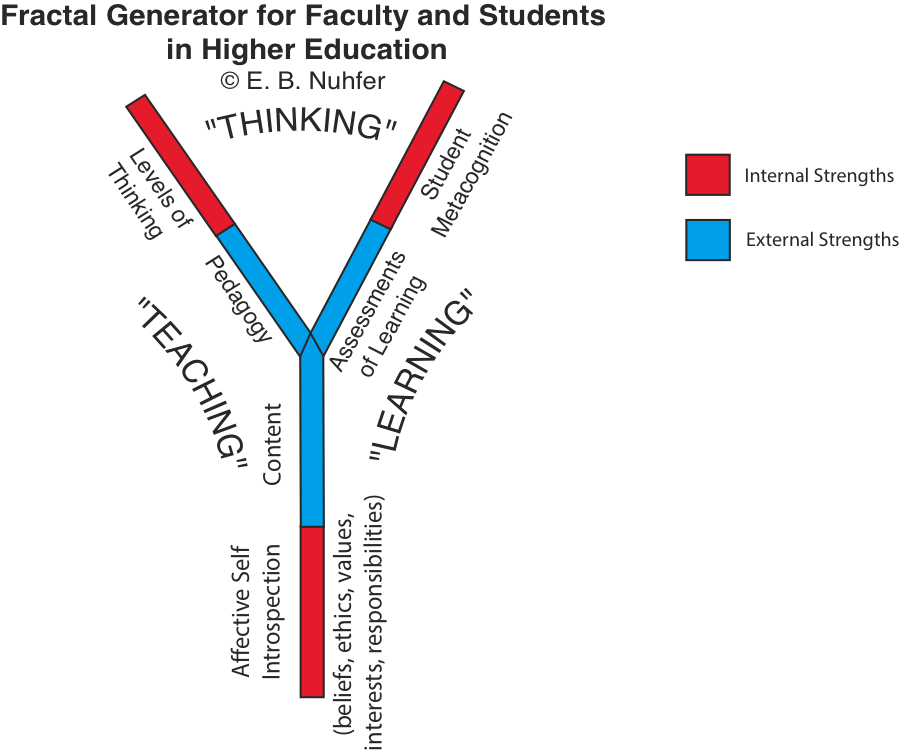

The statement, “Metacognition is thinking about thinking” always triggers the question, “What do we think about?” The fractal generator (Fig. 2) in use by me for about the past two decades tends to trigger six items for consideration in what to “think about” to build an informed philosophy. The meaning of “informed philosophy” extends beyond a document informed by a solid base of research on teaching, learning, and thinking. The term “informed philosophy,” as used here, is a document that reflects the growing understanding of ourselves in concert with our growth in knowledge, skills, and evidence-based practices.

Three components in blue (Fig. 2) are mostly components of skills and knowledge. Development of strengths in these three areas comes mainly (not wholly) from external sources. These include the research provided from the literature and from our network of colleagues who help us to build our content expertise and our awareness of varied pedagogical approaches and assessment practices. These originate primarily from resources from outside self, and we mostly develop our practice by drawing on these contributions.

Figure 2. A fractal generator model for higher education begins with an initiator that is affect. No deliberate efforts to teach or learn are devoid of affective qualities. Without affective desire to learn to value any of the six areas, such areas will not develop. Practice will then grow from a stunted generator.

The components in red that we call “internal strengths” (Fig. 2) require understanding that develops primarily from within us. The initiator for our generator (Fig. 2) is the red line segment at the base of the generator, which represents our affective feelings. Strong affective interest and enthusiasm may be our most valuable assets for guiding learning efforts to success. We needed to want to do something such as attend college, major in an area that felt attractive and to continue acting to achieve expertise by persevering to develop. That desire comes from within. When our affective passion and cognitive focus align for learning, we are unlikely to fail.

Finding Our Initiators from Within

In starting to write a teaching philosophy, a valuable awareness occurs when we query ourselves about how we obtained our present affective desires for what we aspire to do. Recalling an influential mentor often reveals from whom, when, and where that initial desire occurred. Recollecting a mentor’s valued qualities often reveals that how a teacher now hopes to be remembered began to form with learning to appreciate the power and validity of a particular mentor’s qualities. These recollections usually carry strong emotional ties, and early ideas that produced our conceptions of what constitutes good teaching can be beneficial if they really fit us. They can also be limiting if we unconsciously attempt to imitate a revered mentor rather than advance to develop the teaching that arises from our unique experiences and values.

Cultivating the habit of regular metacognitive conversations with ourselves allows us to confront a query of great importance: “Is what I am doing in the present truly what I most intended to do?” If not, the revised philosophy serves to direct our efforts back to regain doing what we intended to do. That practice allows us to tap the optimal power of affect by doing what a plan of deep introspection revealed that we most wanted to do in our practice. When a troubling event starts to occur, a valuable first reflection is, “Am I actually practicing my philosophy through how I am engaging with this challenge?” Often, we will find that troublesome events occur from a brief moment of inattention that sidetracks us into doing something other than what we intended to do.

Fractals and Uniqueness

In the neural networks that store the well-developed expertise within our brains, the separate neural components are in communication with one another, and they enlist one another to engage successfully with challenges or unexpected changes. Thus, the six areas of the generator (Fig. 2) that grow through our experience should grow to work simultaneously in active practice. Although I’ve found no contributions to research in faculty development that cannot be addressed from within the components of Figure 2, the fractal model is not one of prescriptive development. It does not lead to producing instructors in cookie-cutter fashion who all think alike and teach alike. Indeed, it cannot.

For the same reason that there are neither two trees nor two rainstorms that are alike, there can be no two brains that wire alike. Small differences between individuals’ generators occur through the unique experiences of each person. As these differences influence the replication through the repeated exercise of one’s practice, they guarantee the development of diversity and uniqueness of every teacher, every student, and thus every teaching moment experienced within a class. An internalized awareness that these will never occur again leads to consciously respecting others and valuing the present moment deeply.

We have seen in this brief entry how becoming aware of the pervasiveness of fractals in the physical world and understanding the role of the generator helps the author appreciate the utility of a written teaching philosophy for illuminating one’s own generator. Through the recursive process of repeated implementation, robust generators significantly strengthen one’s practice through time. In our next blog entry, we will examine metacognition’s specific roles in developing each of the six individual components.

Nuhfer, E. B. (2007). “The ABCs of fractal thinking in higher education.” To Improve the Academy (25) 70-89.