By John Draeger, SUNY Buffalo State

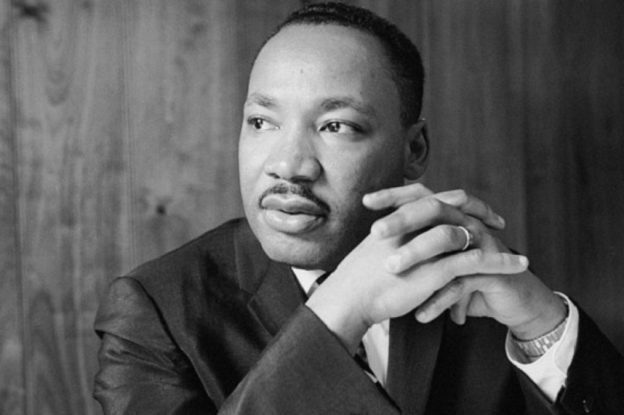

In his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” Martin Luther King Jr. responds to the white moderates of Birmingham who believed his protests were ill-timed and unnecessary. He writes:

I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Council or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to “order” than to justice; who prefers a negative peace which is the absence of tension to a positive peace which is the presence of justice; who constantly says: “I agree with you in the goal you seek, but I cannot agree with your methods of direct action”; who paternalistically believes he can set the timetable for another man’s freedom; who lives by a mythical concept of time and who constantly advises the Negro to wait for a “more convenient season.” Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection. (King, 295)

White moderates baffled King because he knew them to be people of good will. Why would they talk the equality talk without walking the walk? For example, they worried that King’s protests threatened to undermine the rule of law. Yet, King argued that respect for the law and for the human beings governed by those laws, demanded standing against injustice even when, perhaps especially when, it would be convenient for whites to do otherwise. Moreover, King’s respect for the system of law was underscored by the fact that the protests were nonviolent and the protestors were willing to accept the consequences of their lawbreaking. King’s letter challenged the white moderates of Birmingham to consider why they were so reluctant to side with those being treated unjustly. In short, King called on them (and us today) to be more metacognitive.

The Benefits of Metacognition

Metacognition is the ongoing awareness of a process and a willingness to adjust when necessary. King’s letter argued that the white moderates needed to become aware of a broader set of issues and adjust their actions accordingly. For example, white moderates were concerned about the safety of their families and the fact that protests might turn violent. This seems reasonable until we consider the living conditions and often violent treatment of their black neighbors. King suggests that white moderates were emotionally disconnected from the lived experience of those affected by segregation and this disconnect helped explain their tepid endorsement of the civil rights movement. Willful ignorance can shield us from uncomfortable truths about ourselves and the world around us. It is often easier not to ask tough questions than to face unflattering answers. However, metacognition prompts us to consider the quality of our thought processes and then take action based on a new awareness of ourselves.

Raising awareness by purposefully engaging our reasons for action (or non-action) might prompt us to ask the following sorts of metacognitive prompting questions.

- How well do I understand those around me?

- When am I less likely to question what I am doing?

- What are the forces that keep me from being connected to the suffering of others?

- When am I less likely to see the harms done to others? Are the harms invisible (e.g., internal struggles that I could only see with careful listening)? Or would harms be visible to me if I were paying attention?

- Why am I not paying attention to others?

- Do I tend to avoid bad news because ignorance is psychologically easier?

- Am I afraid of asking myself difficult questions because I doubt I can do anything about it anyway?

- Am I afraid to rock the boat?

- Am I afraid to ask questions that will paint me in a bad light?

The list of relevant questions could go on for pages and it will likely depend on the particular circumstances, but it is worth remembering that it was in inability of white moderates to ask such questions led King to write his letter. If we want to avoid similar pitfalls, then each of us must find the wherewithal to take a hard look in the mirror and adjust when necessary.

Looking forward

I find King’s letter especially relevant at a time when many of us are coming to grips with how address issues raised by the #BlackLivesMatter and #MeToo movements as well as the worldwide conversation surrounding immigration. I believe that there are rich research opportunities at the intersection of metacognition and ethical reasoning. For example, how might metacognition help overcome implicit bias or microaggression? How might it support the development of respect for humankind? I hope to consider these issues in future posts.

References

King, M. L. (1963). “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” in A Testament of Hope: The Essential Writings and Speeches of Martin Luther King Jr., ed. James Washington (San Francisco: Harper Collins, 1986).