By Dr. Lauren Scharff, U. S. Air Force Academy *

For many of us, this time of year marks an academic semester’s end. It’s also intertwined with a major holiday season. There is so much going on – pulling our thoughts and actions in a dozen different directions. It almost seems impossible to be metacognitive about what we’re doing while we’re doing it: grading that last stack of exams or papers, finalizing grades, catching up on all those work items that have been on the back burner but need to get done before the semester ends. And that’s just a slice of our professional lives. Add in all the personal tasks and aspirations for these final few weeks of the year, and it’s Go, Go, Go until the day is over.

Well, that was a bit cathartic to get out, but also a bit depressing. Logically I know that by taking the time to reflect and use that awareness to help guide my behaviors (i.e. engage in metacognition), I will feel energized and revitalized because I’ll have a plan with a good foundation. I will more likely be successful in whatever it is I’m hoping to accomplish, especially if I regularly take the time to reflect and fine tune my efforts. But the challenge is, how do I fit it all in?

My proposed solution is micro-metacognition!

So, what do I mean by that? I think micro-metacognition is analogous to taking the stairs whenever you can rather than signing up for a new gym membership. Stairs are readily available at no cost and can be used spur-of-the-moment. In comparison, the gym membership requires a more concerted effort and larger chunks of time to get to the facility, work out, clean up and head home. In the more academic realm, micro metacognition falls in line with the spirit of James Lang’s (2016) Small Teaching recommendations. He advocates for the powerful impact of even small changes in our teaching (e.g. how we use the first 5 minutes of class). In other words, we don’t have to completely redesign a course or our way of teaching to see large benefits.

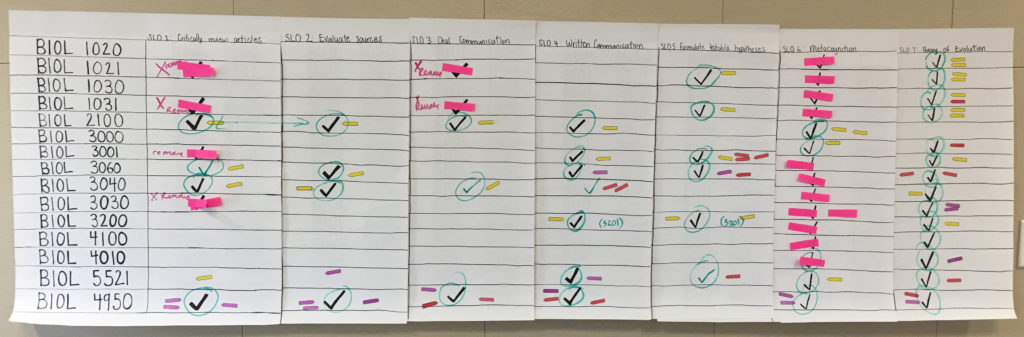

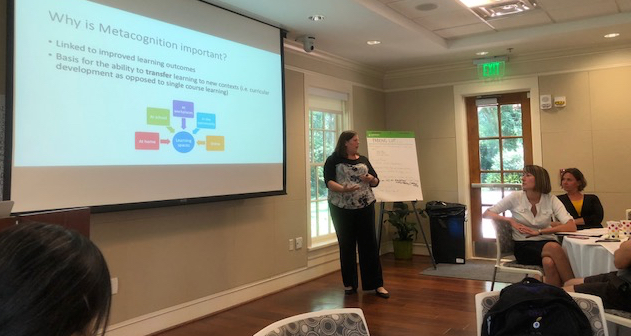

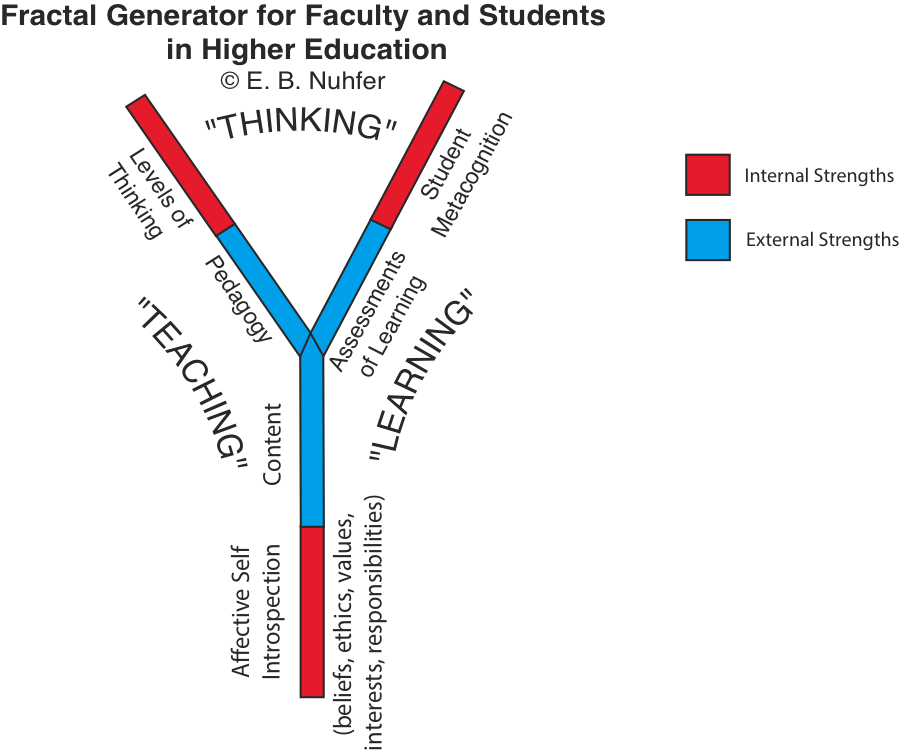

To help place micro-metacognition into context, I will borrow a framework from Poole and Simmons (2013), who suggested a “4M” model for conceptualizing the level of impact of SoTL work: micro (individual/classroom), meso (department/ program), macro (institutional), and mega (beyond a single institution). In this case though, we’re looking at engagement in metacognitive practices, so the entity or level of focus will always be the individual, and the scale will refer to the amount of planning, effort, and time needed for the metacognitive practice. This post focuses on instructors being metacognitive about their practice of teaching, but I believe that parallels can easily be made for students’ engagement in metacognition as they are learning.

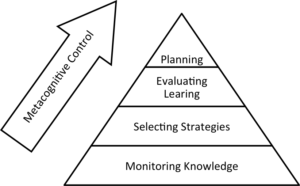

The 4M Metacognition Framework

Micro-metacognition – Use of isolated, low-cost tactics to promote metacognitive instruction when engaged in single tasks (e.g. grading a specific assignment – see below for fleshed out example). These can be used without investments in advance planning.

Meso-metacognition – Use of tactics to promote metacognitive instruction throughout an individual lesson or when incorporating a specific type of activity (e.g. discussion or small group work) across multiple lessons. These tactics have been given more forethought with respect to integration with lesson / activity objectives.

Macro-metacognition – Use of more regular tactics to promote metacognitive instruction across an entire course / semester. Planning for these would be more long-term and closely integrated with learning objectives for the course or with professional development goals of the instructor. (For an example of this level of effort, see Use of a Guided Journal to Support Development of Metacognitive Instructors.)

Mega-metacognition – Use of tactics to promote metacognitive instruction across an instructor’s entire set of courses and professional activities (and beyond). At this level of engagement, metacognition will likely be a “way of doing things” for the instructor, but each new engagement will still require conscious effort and planning to support goals and objectives.

An Example of Micro Metacognition

Micro-metacognition efforts are not pre-planned when the instructional task is planned; they are added later as the idea crosses the instructor’s mind and opportunity arises.

For example, when I am about to start grading a specific group of papers, I might reflect that in addition to the formally-stated learning objectives that will be assessed on the rubric, I want to support growth mindset in my students for their future writing efforts. This additional goal could come about from a recent reading on mindset or discussion with my colleagues. I know that I would be likely to forget this goal when I’m focused on the other rubric aspects of the grading. So, I write that goal on a stickie note and put it where I am likely to see it when grading. Then, when I am grading, I have an easy-to-implement awareness aide to add comments in the papers that might specifically support my students’ growth mindset.

In sum: easily implemented stickie note –> promotes awareness of goal –> self-regulation of desired grading behavior on that specific instructional task == Micro-metacognitive Instruction!

I can think of lots of other ways instructors might incorporate micro-metacognition in their instructional endeavors, from the proverbial string tied to one’s finger, to pop-up calendar prompts, to asking a student for a reminder to attend to questions when we get to a particular topic. Or, awareness might come without an intentional prompt. The key is to then use that awareness to self-regulate some aspect of our instructional behavior in support of student learning and development. The opportunities are endless!

I hope you are motivated as you enter the new year. Happy holidays!

——————-

Lang, J. M. (2016). Small teaching: Everyday lessons from the science of learning.

Poole, G., & Simmons, N. (2013). The contributions of the scholarship of teaching and learning to quality enhancement in Canada. In G. Gordon, & R. Land (Eds.). Quality enhancement in higher education: International perspectives (pp. 118-128). London: Routledge.

* Disclaimer: The views expressed in this document are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U. S. Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U. S. Govt.