by Patrick Cunningham, Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology

I’m a mechanical engineering professor and since my first teaching experience in graduate school I’ve wanted my students to walk away from my classes with deep learning. Practically, I want my students to remember and appropriately apply key concepts in new and different situations, specifically while working on real engineering problems.

In my early years of teaching, I thought if I just used the right techniques, exceptional materials, the right assignments, or the right motivational contexts, then I would get students to deeper learning. However, I still found a disconnect between my pedagogy and student learning. Good pedagogy is important, but it isn’t enough.

On sabbatical 4 years ago, I sat in on a graduate-level cognitive processes course that helped explain this disconnect. It helped me realize student learning is principally determined by the student. What the student does with the information determines the quality of their learning. How they use it. How they apply it. How they practice it. How engaged they are with it. I can provide a context conducive to deeper learning, but I cannot build the foundational and rich knowledge frameworks within the students’ minds. Only the students can do this. In other words, while we, as educators, are important in the learning process, we are not the primary determinants of learning, students are. Students are responsible for their learning, but they don’t universally realize it.

So, how do we help students realize their responsibility for learning? It requires presenting explicit instruction on how learning really works, providing practice with effective approaches to learning, and giving constructive feedback on the learning process (Kaplan, et al. 2013). When left unchecked, flawed conceptions of the learning process at best are allowed to persist and at worst are reinforced. Even when we do not explicitly speak to the learning process with our students, we say something about it. For example, when our primary mode of instruction is walking students through example problems, we may reinforce the belief that learning is about memorizing the process rather than connecting concepts to different contexts and knowing when to apply one concept versus another concept. Sometimes we do speak to students about the learning process, but we offer vague and unhelpful advice, such as, “work more problems”, or “study harder”. Such advice doesn’t point students to specific strategies instrumental in building more interconnected knowledge frameworks (e.g., elaborative and organizational strategies) (Dembo & Seli 2013) and can reinforce surface-level memorization and pattern matching approaches.

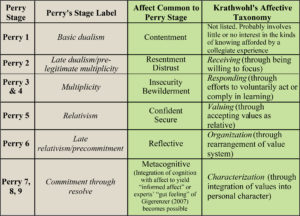

Because our teaching doesn’t guarantee student learning, because we desire our students develop deep and meaningful learning, and since we always say something about the learning process (intentionally or not), we, as educators, are responsible for engaging our students in developing as learners. We should be explicitly engaging our students in learning about and regulating their learning processes, i.e., developing their metacognitive skills.

As I advocate for our responsibility to aid students’ in learning how to learn, some common reactions include:

- Don’t people figure out how to learn naturally?

- Shouldn’t students already do this on their own?

- I don’t know metacognition and the science of learning like I know my specialty area.

Don’t we figure out how to learn naturally? Yes, learning is a natural process, but, no, we do not naturally develop deep and efficient approaches to learning – anymore than we naturally develop the skill of a concert musician or any other highly refined practice. Shouldn’t students already do this on their own? Ideally, yes, but the reality is most students’ prior learning experiences have led to ingrained surface learning habits.

Prior learning experiences condition how we go about learning, along with contextual factors, such as the guidance of parents and teachers. In general, students think they are good at learning and don’t see a need to change their approaches. They continue to get good grades using memorization and pattern matching – often cramming for exams – while lacking long-term memory of concepts and the ability to transfer these concepts to real applications. As long as our courses allow students to get good grades (their measures of “success”) with surface learning habits, such views will persist. Deep learning includes memorizing, i.e., knowing, things, but such durable and transferable learning requires much more than just memorization. It takes effortful intellectual engagement with concepts, exploring connections and sorting out relationships between concepts, and accurate self-assessment. Such approaches can be learned, and a few students do. More can if we explicitly guide them. Our students are not lazy, rather they are misguided by prior experiences. Let’s guide them!

I don’t know metacognition and the science of learning like I know my specialty area. Yes, it is important to be knowledgeable and proficient with what we teach. While we have done much with the content in our specialties, we have limited training, if any, training on metacognition (the knowledge and regulation of our thinking/learning processes) and the science of learning. However, as educators trying to improve our craft, shouldn’t we also be students of learning? This can start small and continue as a career-long pursuit. We can always improve! You also likely know more than you think you do. Your self-selection into advanced studies and a college teaching career are not an accident. As part of the select group of academics, you are likely already metacognitively skilled, even if you don’t realize it. Start small, with one thing. Learn about it and practice or recognize it in your own life. For example, peruse a copy of Linda Nilson’s Creating Self-Regulated Learners or James Lang’s Small Teaching, or attend a teaching workshop that sparks your interest. Then, confidently share it with your students and engage them in it as you teach your content. Your authentic experience with it demonstrates its relevance and importance. Once you have become comfortable with this, add another element. Over time, you will build practical expertise about the learning process. Along the way you will likely learn about yourself and make sense of your past (and present) learning experiences. I did!

Need help? Look for my next post, “Where should I start with metacognition?”

Acknowledgements

This blog post is based upon metacognition research supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Nos. 1433757, 1433645, & 1150384. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. I also extend my gratitude to my collaborating researchers, Dr. Holly Matusovich and Ms. Sarah Williams, for their support and critical feedback.

References

Dembo, M. & Seli, H. (2013). Motivation and Learning Strategies for College Success: A Focus on Self-Regulated Learning (4th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Kaplan, M., Silver, N., Lavaque-Manty, D., Meizlish, D. (Eds.). (2013). Using Reflection and Metacognition to Improve Student Learning. Sterling, VA: Stylus.