by John Draeger, SUNY Buffalo State

In an earlier post, Lauren Scharff and I argued that metacognition can help instructors select and apply appropriate teaching strategies (Draeger & Scharff, 2016). More specifically, we argued that metacognition encourages instructors to consider the particulars of each learning environment (e.g., student background, learning goals, classroom culture) and we offered a series of question prompts to guide the conversation (e.g., what are you doing to check-in with students? What strategy adjustments might you make?). This post extends that work by offering two additional conceptual anchors to ground discussion, namely fundamental concepts and bottlenecks.

First, fundamental concepts can serve as a conceptual anchor for metacognitive instruction. Gerald Nosich describes fundamental and powerful concepts as those “core ideas used to organize other ideas and unlock important questions, insights, and discoveries” (Nosich, 2012). When designing a course, fundamental concepts guide my dec isions regarding how much to cover and how much time to devote to a particular topic. As I am making choices, I ask myself “how does this material help students better understand the fundamental concept of the course?” In assessment, I want my assignments to align with the most important aspects of the course and fundamental concepts articulate those important features. And in class instruction, fundamental concepts guide class conversation and provide a mechanism for refocusing peripheral lines of questioning. Therefore, if metacognitive instruction encourages me to be intentional about my learning objectives and student progress towards achieving them, then fundamental concepts serve as a constant reminder to me (and my students) of what is most important.

isions regarding how much to cover and how much time to devote to a particular topic. As I am making choices, I ask myself “how does this material help students better understand the fundamental concept of the course?” In assessment, I want my assignments to align with the most important aspects of the course and fundamental concepts articulate those important features. And in class instruction, fundamental concepts guide class conversation and provide a mechanism for refocusing peripheral lines of questioning. Therefore, if metacognitive instruction encourages me to be intentional about my learning objectives and student progress towards achieving them, then fundamental concepts serve as a constant reminder to me (and my students) of what is most important.

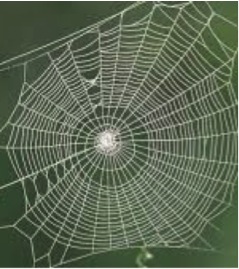

By way of illustration, the concept of justice is fundamental concept to my upper division course in philosophy of law. The course readings are roughly subdivided into theoretical discussions that articulate particular philosophical conceptions of justice (e.g., procedural, moral) and applications in the law (e.g., landmark United States Supreme court cases). The theories illuminate elements in the court cases and the cases provide illustrations of the theoretical features. Without explicit reference to a fundamental concept, the course can seem like an endless list of court cases with each case, and each detail of each case, seeming as important as all the others. Through an explicit focus on the fundamental concept, however, the course is organized around a conceptual web with justice at the center and theories and cases emanating out in order of importance (e.g., theories can articulate conceptions of justice and cases can be organized according to those conceptions). As someone aspiring to practice metacognitive instruction, I regularly check-in with students and make adjustments based on class discussion. When students seem to be “in the weeds,” I can use the concept of justice (and our various conceptions of it) as a way to refocus the conversation on what is most important to the course. We can then build back the details of the theories and the cases. Further, some students relish the details of cases, but they are less inclined to consider how the cases illustrate the theories that we’ve been reading. Again, the concept of justice allows me to reframe class conversation and build back the structural details of the course (e.g., theories of justice, court cases). Finally, I make adjustments in my preparation between class sessions based on my informal assessment of student understanding in relation to the fundamental concept. In this way, fundamental concepts work in conjunction with my efforts to be a metacognitive instructor.

A second type of conceptual anchor for metacognitive instruction can be found by considering the bottlenecks of a given course. Middendorf and Pace (2004) describe course bottlenecks as aspects of the course (concepts/skills) that are both essential to the course and places where students consistently struggle. Students in my philosophy of law courses, for example, often confuse descriptive claims (how things are) with normative claims (how things should be). This confusion can cause students to be frustrated by class discussion and flummoxed by written assignments. For example, students in the grips of this confusion tend to focus on the fact that the U.S. Supreme Court reached a decision by a 5-4 margin without consid ering that it can (or perhaps even should have been otherwise). They reason that if the court ruled this way, then that’s the end of the story (descriptive claim about how the law is). These students tend not to consider whether the court might have been mistaken in their ruling (a normative question). Even if these students memorize court rulings and the rationale for those decisions, they have not yet engaged with the normative underpinnings of the course (e.g., whether a particular ruling is just). As someone trying to practice metacognitive instruction, I need to monitor student progress and make necessary adjustments. Bottlenecks (e.g., student struggles with normative questions) give me a predictable place to check-in and refocus student attention.

ering that it can (or perhaps even should have been otherwise). They reason that if the court ruled this way, then that’s the end of the story (descriptive claim about how the law is). These students tend not to consider whether the court might have been mistaken in their ruling (a normative question). Even if these students memorize court rulings and the rationale for those decisions, they have not yet engaged with the normative underpinnings of the course (e.g., whether a particular ruling is just). As someone trying to practice metacognitive instruction, I need to monitor student progress and make necessary adjustments. Bottlenecks (e.g., student struggles with normative questions) give me a predictable place to check-in and refocus student attention.

Moreover, given that the fact I can anticipate that students are likely to struggle with normative questions (the bottleneck of the course), I am more intentional about course design, instruction, and feedback on assessment. For example, I intentionally begin the course with Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” because King’s argument makes it clear that there is such a thing as an unjust law. We then follow up by considering a number of landmark cases early in the semester, such as Plessy v. Ferguson and Brown v. Board of Education. In the former, the court supported the “separate but equal” doctrine. In the latter, they rejected it. We talk about what made the Plessy unjust and why Brown readdresses that injustice. This launches into more theoretical discussions about the types of reasoning offered in those decisions and how they are related to the fundamental concept of justice. By considering these cases, students have early illustrations of a just and unjust law (normative claims). This exercise becomes a touchstone for later in the semester when students struggle with the descriptive and normative distinction. Because metacognitive instruction demands that I regularly check-in, I am tuned into the fact that students are often stuck in the normative bottleneck . When this happens, we can revisit our conversations about King, Plessy and Brown. Moreover, if this teaching strategy doesn’t work, then I know that I need to choose another strategy. Student understanding will be stymied unless I can help them overcome predictable confusions. Clearing the bottleneck, therefore, can open up learning opportunities, but clearing the bottleneck only happens if I am aware of student difficulties and willing to make changes (i.e. metacognitive instruction).

This post has built on the thought that metacognitive instruction can help instructors choose appropriate instructional strategies. In particular, fundamental concepts can help instructors be intentional and explicit about what is most important about their courses. Likewise, locating consistent sources of student difficulty can help frame where and how instructional energies can be best spent. In short, both fundamental concepts and bottlenecks ground metacognitive instruction by providing anchor points and guiding instructors towards promising teaching strategies.

References

Draeger, J. & Scharff, L. (2016). “Using Metacognition to select and apply appropriate teaching strategies.”Retrieved from https://www.improvewithmetacognition.com/using-metacognition-select-apply-appropriate-teaching-strategies/

Middendorf, J., & Pace, D. (2004). Decoding the disciplines: A model for helping students learn disciplinary ways of thinking. New directions for teaching and learning, 2004(98), 1-12.

Nosich, G. (2012) Learning to think things through: A guide to critical thinking across the disciplines. Saddle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall.