by Steven Fleisher, Ph.D., California State University Channel Islands

I have heard many express that teacher-student relationships have nothing in common with families. But while teacher-student relationships are best described as collegial, at least within higher-education, this author believes that much can be learned from family theories and research. In particular, family research provides insights into how to support the development of trust in this context rather than relationships based principally on compliance. In other words, a classroom “is” a family, whether it’s a good one or a bad one. In this posting, we will explore metacognitive processes involved in building and maintaining stable relationships between students and the curriculum, teachers and the curriculum, and between teachers and students.

Family systems theory (Kerr & Bowen, 1988), though originally developed for clinical practice, offers crucial insights into not only teacher-student relationships but teaching and learning as well (Harrison, 2011). While there are many interlocking principles within family systems theory, we will concentrate on emotional stability, differentiation of self, and triangles.

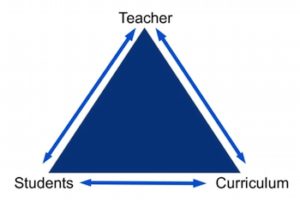

The above triangle provides a representation for the following relationships: students-curriculum, teacher-curriculum, and teacher-students. Although any effective pedagogy would work for this discussion, we will focus specifically on the usefulness of knowledge surveys in this context (http://elixr.merlot.org/assessment-evaluation/knowledge-surveys/knowledge-surveys2) and their role in building metacognitive self-assessment skills.[1] Thus, what are some of the metacognitive processes involved in the relationships on each leg of our triangle? And, what are some of the metacognitive processes that would support those relationships in becoming increasingly stable?

Student-Curriculum Relationships

Along one leg of the triangle, students would increase the stability of their relationships with the curriculum as a function of becoming ever more aware of their learning processes. Regarding the use of knowledge surveys, students would self-assess their confidence to respond to given challenges, compare those responses with their developed competencies, and follow with reflective exercises to discover and understand any gaps between the two. As their self-assessment accuracy improves, their self-regulation skills would improve as well, i.e., adjusting, modifying, or deepening learning strategies or efforts as needed. So, the more students are aware of competencies in the curriculum and the more aware they are of their progress towards those competencies, the better off students will be.

As part of a course, instructors can also guide students in exploring how the material is useful to them personally. Activities can be designed to support exploration and discovery of ways in which course material relates, for example, to career interests, personal growth, interdisciplinary objectives, fostering of purpose, etc. In so doing, the relationships students have with the material can gain greater stability. Ertmer and Newby (1996) noted that expertise in learning involves becoming “strategic, self-regulated, and reflective”, and by bringing these types of exercises into the course, students are supported in the development of all these competencies.

Teacher-Curriculum Relationships

These relationships involve teachers becoming more aware of their practices, their student’s learning, and the connection between their practices and their student’s learning. In other words, the teacher is trying to ensure fit between student understanding and curriculum. Regarding knowledge surveys, teachers would know they are providing a pedagogical tool that supports learning and offers needed visibility for students.

In addition, once teachers have laid out course content in their knowledge surveys, they can look ahead and anticipate which learning strategies would be the best match for upcoming material. Realizing ahead of time the benefits of, let’s say, using structured group work for a particular learning module, teachers could prepare themselves and their students for that type of activity.

Teacher-Student Relationships

These relationships involve the potential for the development of trust. When trust develops in a classroom, students not only know what the expectations involve but are set more at ease to explore creatively their understanding and ways of understanding the material. For instance, students may well become aware of the genuine and honest help being provided by chosen learning strategies. Knowledge surveys are particularly useful in this regard as students have a roadmap for the course and a tool structured to facilitate the improvement of their learning skills.

Teachers also have an interpersonal role in supporting the development of student trust. Family systems theory (Bowen & Kerr, 1988) holds that we all vary in our levels of self-differentiation, which involves how much we, literally, realize that we are separate from others, especially during emotional conflict. In other words, people vary in their abilities to manage emotional reactivity (founded in anxiety) with being able to use one’s intellect to compose chosen and valued responses. Harrison (2011), in applying these principles in a classroom, noted that when teachers are aware of becoming emotionally reactivity (i.e., defensive), but are also aware of using their intellect, as best as possible, to manage the situation (i.e., remaining thoughtful and unbiased in their interactions with students), they are supporting emotional stability and trust.

Kerr and Bowen (1988) also reported that self-differentiation involves distinguishing between thoughts and feelings. This principle gives us another metacognitive tool. When we are aware, for example, that others do not “make” us feel a certain way (i.e., frustrated), but that it involves also our thinking (i.e., students are just being lazy), this affects our ability to manage reactivity. If we are aware of becoming reactive, and aware of distinguishing thoughts and feelings, we can notice and reframe our thoughts (i.e., students are just doing what they need to do), and validate and own our emotions (i.e., okay I’m frustrated), then we are better positioned to respond in ways that attune to our needs as well as those of our students. In this way, we would increase our level of self-differentiation by moving toward less blaming and more autonomy.

Final Note

Kerr and Bowen (1988) also said that supporting stability along all the relationships represented by our triangle not only increases the emotional stability of the system, but provides a cushion for the naturally arising instabilities along individual legs of the triangle. This presence of this stability also serves to further enhance the impact of effective pedagogies. So, when teachers are aware of maintaining the efficacy of their learning strategies, and are aware of applying the above principles of self-differentiation, i.e. engaging in metacognitive instruction, they are better positioned to be responsive and attuned to the needs of their students, thus supporting stability, trust, and improved learning.

References

Ertmer, P. A. & Newby, T. J. (1996). The expert learner: Strategic, self-regulated, and reflective. Instructional Science, 24(1), 1-24. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/journal/11251

Harrison, V. A. (2011). Live learning: Differentiation of self as the basis for learning. In O.C. Bregman & C. M. White (Eds.), Bringing systems thinking to life: Expanding the horizons for Bowen family systems theory (pp. 75-87). New York, NY: Routledge.

Kerr, M. E. & Bowen, M. (1988). Family evaluation: An approach based on Bowen theory. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Image from: https://www.slideshare.net/heatherpanda/essay-2-for-teaching-course-4

[1] Knowledge surveys are comprised of a detailed listing of all learning outcomes for a course (perhaps 150-250 items). Each item begins with an affective root (“I can…”) followed by a cognitive or ability challenge expressed in measurable terms (“…describe at least three functions of the pituitary gland.”). These surveys provide students with a roadmap for the course and a tool structured for building their confidence and accuracy in learning skills.