by Amy Ratto Parks, Ph.D., University of Montana

If I had to choose the frustration most commonly expressed by students about writing it is this: the rules are always changing. They say, “every teacher wants something different” and because of that belief, many of them approach writing with feelings ranging from nervous anxiety to sheer dread. It is true that any single teacher will have his or her own specific expectations and biases, but most often, what students perceive as a “rule change” has to do with different disciplinary expectations. I argue that metacognition can help students anticipate and negotiate these shifting disciplinary expectations in writing courses.

Let’s look at an example. As we approach the end of spring semester, one single student on your campus might hold in her hand three assignments for final writing projects in three different classes: literature, psychology, and geology. All three assignments might require research, synthesis of ideas, and analysis – and all might be 6-8 pages in length. If you put yourself in the student’s place for a moment, it is easy to see how she might think, “Great! I can write the same kind of paper on three different topics.” That doesn’t sound terribly unreasonable. However, each of the teachers in these classes will actually be expecting some very different things in their papers: acceptable sources of research, citation style and formatting, use of the first person or passive voice (“I conducted research” versus “research was conducted”), and the kinds of analysis are very different in these three fields. Indeed, if we compared three papers from these disciplines we would see and hear writing that appeared to have almost nothing in common.

So what is a student to do? Or, how can we help students anticipate and navigate these differences? The fields of writing studies and metacognition have some answers for us. Although the two disciplines are not commonly brought together, a close examination of the overlap in their most basic concepts can offer teachers (and students) some very useful ways to understand the disciplinary differences between writing assignments.

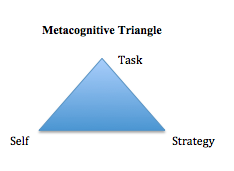

Rhetorical constructs are at the intersection of the fields of writing studies and metacognition because they offer us the most clear illustration of the overlap between the way metacognitive theorists and writing researchers conceptualize potential learning situations. Both fields begin with the basic understanding that learners need to be able to respond to novel learning situations and both fields have created terminology to abstractly describe the characteristics of those situations. Metacognitive theorists describe those learning situations as “problem-solving” situations; they say that in order for a student to negotiate the situation well, she needs to understand the relationship between herself, the task, and the strategies available for the task. The three kinds of problem-solving knowledge – self, task, and strategy knowledge – form an interdependent, triangular relationship (Flavell, 1979). All three elements are present in any problem-solving situation and a change to one of the three requires an adjustment of the other two (i.e., if the task is an assignment given to whole class, then the task will remain the same; however, since each student is different, each student will need to figure out which strategies will help him or her best accomplish the task).

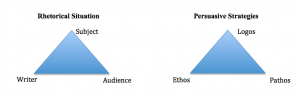

The field of writing studies describes these novel learning situations as “rhetorical situations.” Similarly, the basic framework for the rhetorical situation is comprised of three elements – the writer, the subject, and the audience – that form an interdependent triangular relationship (Rapp, 2010). Writers then make strategic persuasive choices based upon their understanding of the rhetorical situation.

In order for a writer to negotiate his rhetorical situation, he must understand his own relationship to his subject and to his audience, but he also must understand the audience’s relationship to him and to the subject. Once a student understands these relationships, or understands his rhetorical situation, he can then conscientiously choose his persuasive strategies; in the best-case scenario, a student’s writing choices and persuasive strategies are based on an accurate assessment of the rhetorical situation. In writing classrooms, a student’s understanding of the rhetorical situation of his writing assignment is one pivotal factor that allows him to make appropriate writing choices.

Theorists in metacognition and writing studies both know that students must be able to understand the elements of their particular situation before choosing strategies for negotiating the situation. Writing studies theorists call this understanding the rhetorical situation while metacognitive theorists call it task knowledge, and this is where two fields come together: the rhetorical situation of a writing assignment is a particular kind of problem-solving task.

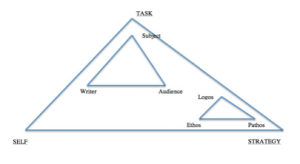

When the basic concepts of rhetoric and metacognition are brought together it is clear that the rhetorical triangle fits inside the metacognitive triangle and creates the meta-rhetorical triangle.

The meta-rhetorical triangle offers a concrete illustration of the relationship between the basic theoretical frameworks in metacognition and rhetoric. The subject is aligned with the task because the subject of the writing aligns with the guiding task and the writer is aligned with the self because the writerly identity is one facet of a larger sense of self or self-knowledge. However, audience does not align with strategy because audience is the other element a writer must understand before choosing a strategy; therefore, it is in the center of the triangle rather than the right side. In the strategy corner, however, the meta-rhetorical triangle includes the three Aristotelian strategies for persuasion, logos, ethos, and pathos (Rapp, 2010). When the conceptual frameworks for rhetoric and metacognition are viewed as nested triangles this way, it is possible to see that the rhetorical situation offers specifics about how metacognitive knowledge supports a particular kind problem-solving in the writing classroom.

So let’s come back to our student who is looking at her three assignments for 6-8 papers that require research, synthesis of ideas, and analysis. Her confusion comes from the fact that although each requires a different subject, the three tasks are appear to be the same. However, the audience for each is different, and although she, as the writer, is the same person, her relationship to each of the three subjects will be different, and she will bring different interests, abilities, and challenges to each situation. Finally, each assignment will require different strategies for success. For each assignment, she will have to figure out whether or not personal opinion is appropriate, whether or not she needs recent research, and – maybe the most difficult for students – she will have to use three entirely different styles of formatting and citation (MLA, APA, and GSA). Should she add a cover page? Page numbers? An abstract? Is it OK to use footnotes?

These are big hurdles for students to clear when writing in various disciplines. Unfortunately, most faculty are so immersed in our own fields that we come to see these writing choices as obvious and “simple.” Understanding the way metacognitive concepts relate to rhetorical situations can help students generalize their metacognitive knowledge beyond individual, specific writing situations, and potentially reduce confusion and improve their ability to ask pointed questions that will help them choose appropriate writing strategies. As teachers, the meta-rhetorical triangle can help us offer the kinds of assignment details students really need in order to succeed in our classes. It can also help us remember the kinds of challenges students face so that we can respond to their missteps not with irritation, but with compassion and patience.

References

Flavell, J.H. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new era cognitive development inquiry. American Psychologist, 34, 906-911.

Rapp, C. (2010). Aristotle’s Rhetoric. In E. Zalta (Ed.), The stanford encyclopedia of

philosophy. Retrieved from http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2010/entries/aristotle-rhetoric/