by Ashley Welsh, Postdoctoral Teaching & Learning Fellow, Vantage College

I am a course coordinator and instructor for a science communication course (SCIE 113) for first-year science students. SCIE 113 focuses on writing, argumentation and communication in science and is part of the curriculum for an enriched, first-year experience program for international, English Language Learners. Throughout the term, students provide feedback on their peers’ writing in both face-to-face and online environments. The process of providing and receiving feedback is an important skill for students, however many students do not receive explicit instruction on how to provide or use constructive feedback (Mulder, Pearce, & Baik, 2014). In order to better understand my students’ experience with peer review, I conducted a research project to explore how their use and perceptions of peer review in their writing developed over the course of the term.

Many of the data collection methods I used to assess students’ perceptions and use of peer review in SCIE 113 this past term incorporated acts of reflection. These included in-class peer review worksheets and written reflections, small and large group discussions, an end-of-term survey about peer review, and my own researcher reflections. Periodically throughout the semester, I paired up the students and they engaged in peer review of one another’s writing. They each had a worksheet that asked them to comment on what their partner did well and how that person could improve their writing. During this activity, my teaching assistant and I interacted with the pairs and answered any potential questions. Afterwards, students independently completed written reflections about the usefulness of the peer review activity and their concerns about giving and receiving feedback. Before the class finished, we discussed students’ responses and concerns as a whole group. Students’ worksheets and written reflections, as well as classroom observations, offered insight into how my pedagogy mapped to their use of and reflections about peer review.

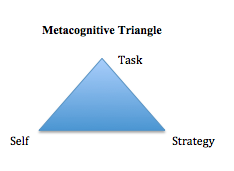

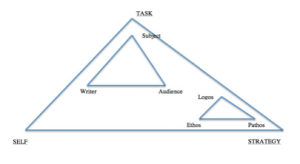

As of late, I have been more deliberate with designing pedagogy and activities that offer students the time and space to reflect and record their strengths and weaknesses as learners. The term reflection, is often used when discussing metacognition. As Weinert (1987) describes, metacognition involves second-order cognitions such as thoughts about thoughts or the reflections of one’s actions. With respect to metacognitive regulation, Zohar and Barzilai (2013) highlight that an individual can heighten their awareness of their strengths/weaknesses and evaluate their progress via reflection. This reflection process also plays a key role in metacognition-focused data collection as most methods require students to reflect upon how their knowledge and skills influence their learning. Providing survey responses, answering interview questions, and writing in a journal require a student to appraise their personal development and experience as a learner through reflection (Kalman, 2007; Aktruk & Sahin, 2011).

While the act of reflection is an important component of metacognition and metacognitive research, its use in the classroom also presents its own set of challenges. As educators and researchers, we must be wary of not overusing the term so that it remains meaningful to students. We must also be cautious with how often we ask students to reflect. An extensive case study by Baird and Mitchell (1987) revealed that students become fatigued if they are asked to reflect upon their learning experiences too often. Furthermore, we hope these acts of reflection will help students to meaningfully evaluate their learning, but there is no guarantee that students will move beyond simplistic or surface responses. To address these challenges in my own classroom, I attempted to design activities and assessments that favoured “not only student participation and autonomy, but also their taking responsibility for their own learning” (Planas Lladó et al., p. 593).

While I am still in the midst of analyzing my data, I noticed over the course of the semester that students became increasingly willing to complete the reflections about peer review and their writing. At the beginning of the term, students wrote rather simplistic and short responses, but by the end of the term, students’ responses contained more depth and clarity. I was surprised that students were not fatigued by or reluctant to complete the weekly reflections and discussions about peer review and that this process became part of the norm of the classroom. Students also became faster with completing their written responses, which was promising given that they were all English Language Learners. As per John Draeger (personal communication, April 27, 2016), students’ practice with these activities appears to have helped them build the stamina and muscles required for successful and meaningful outcomes. It was rewarding to observe that within class discussions and their reflections, students became better aware of their strengths and weaknesses as reviewers and writers (self-monitoring) and often talked or wrote about how they could improve their skills (self-regulation).

Based on my preliminary analysis, it seems that tying the reflection questions explicitly to the peer review process allowed for increasingly meaningful and metacognitive student responses. The inclusion of this research project within my class served as an impetus for me to carefully consider and question how my pedagogy was linked to students’ perceptions and ability to reflect upon their learning experience. I am also curious as to how I can assist students with realizing that this process of reflection can improve their skills not only in my course, but also in their education (and dare I say life). This research project has served as an impetus for me to continue to explore how I can better support students to become more metacognitive about their learning in higher education.

References

Akturk, A. O., & Sahin, I. (2011). Literature review on metacognition and its measurement. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 3731-3736.

Baird, J. R., & Mitchell, I. J. (1987). Improving the quality of teaching and learning. Melbourne, Victoria: Monash University Press.

Kalman, C. S. (2007). Successful science and engineering teaching in colleges and universities. Bolton, Massachusetts: Anker Publishing Company, Inc.

Mulder, R.A., Pearce, J.M., & Baik, C. (2014). Peer review in higher education: Student perceptions before and after participation. Active Learning in Higher Education, 15(2), 157-171.

Planas Lladó, A., Feliu Soley, L., Fraguell Sansbelló, R.M., Arbat Pujolras, G., Pujol Planella, J., Roura-Pascual, N., Suñol Martínez, J.J., & Montoro Moreno, L. (2014). Student perceptions of peer assessment: An interdisciplinary study. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(5), 592-610.

Weinert, F. E. (1987). Introduction and overview: Metacognition and motivation as determinants of effective learning and understanding. In F. E. Weinert & R. H. Kluwe (Eds.), Metacognition, motivation, and understanding (pp. 1-16). Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Zohar, A., & Barzilai, S. (2013). A review of research on metacognition in science education: Current and future directions. Studies in Science Education, 49(2), 121-169.