In this post by by Leonard Geddes, Transforming Your Tutoring Program: How to Move Beyond Important to Being Impactful, he makes a case for training tutors so that they can help their clients become metacognitive learners. The post is largely an advertisement for a LearnWell webinar, but the idea of training tutors seems worthwhile.

Year: 2015

Goal Monitoring in the Classroom

by Tara Beziat at Auburn University at Montgomery

What are your goals for this semester? Have you written down your goals? Do you think your students have thought about their goals and written them down? Though these seem like simple tasks, we often do not ask our students to think about their goals for our class or for the semester. Yet, we know that a key to learning is planning, monitoring and evaluating one’s learning (Efklides, 2011; Nelson, 1996; Schraw and Dennison, 1994; Nelson & Narens, 1994). By helping our students engage in these metacognitive tasks, we are teaching them how to learn.

Over the past couple of semesters, I have asked my undergraduate educational psychology students to complete a goal-monitoring sheet so they can practice, planning, monitoring and evaluating their learning. Before we go over the goal-monitoring sheet, I explain the learning process and how a goal-monitoring sheet helps facilitate learning. We discuss how successful students set goals for their learning, monitor these goals and make necessary adjustments through the course of the semester (Schunk, 1990). Many first-generation students and first-time freshman come to college lacking self-efficacy in academics and one set back can make them feel like college is not for them (Hellman, 1996). As educators we need to help them understand we all make mistakes and sometimes fail, but we need to make adjustments based on those failures not quit.

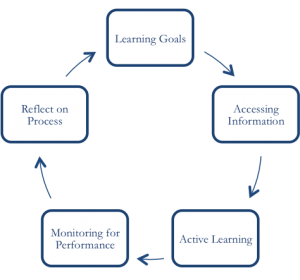

Second, I talk with my class about working memory, long-term memory, and how people access information in one of two ways: verbally or visually (Baddeley, 2000, 2007). Seeing and/or hearing the information does not make learning happen. As a student, they must take an active role and practice retrieving the information (Karpicke & Roediger, 2008; Roediger & Butler, 2011). Learning takes work. It is not a passive process. Finally, we discuss the need to gauge their progress and reflect on what is working and what is not working. On the sheet I reiterate what we have discussed with the following graphic:

After this brief introduction about learning, we talk about the goal-monitoring sheet, which is divided into four sections: Planning for Success, Monitoring your Progress, Continued Monitoring and Early Evaluation and Evaluating your Learning. Two resources that I used to make adjustments to the initial sheet were the questions in Tanner’s (2012) article on metacognition in the classroom and the work of Gabrielle Oettingen (2014). Oettigen points out that students need to consider possible obstacles to their learning and evaluate how they would handle them. Students can use the free WOOP (Wish, Outcome, Obstacle, Plan) app to “get through college.”

Using these resources and the feedback from previous students, I created a new goal-monitoring sheet. Below are the initial questions I ask students (for the full Goal Monitoring Sheet see the link at the bottom):

- What are your goals for this class?

- How will you monitor your progress?

- What strategies will you use to study and prepare for this class?

- When can you study/prepare for this class?

- Possible obstacles or areas of concern are:

- What resources can you use to achieve your goals?

- What do you want to be able to do by the end of this course?

Interestingly, many students do not list me, the professor as a resource. I make sure to let the students know that I am available and should be considered a resource for the course. As students, move through the semester they submit their goal-monitoring sheets. This continuing process helps me provide extra help but also guide them toward necessary resources. It is impressive to see the students’ growth as they reflect on their goals. Below are some examples of student responses.

- “I could use the book’s website more.”

- “One obstacle for me is always time management. I am constantly trying to improve it.”

- “I will monitor my progress by seeing if I do better on the post test on blackboard than the pre test. This will mean that I have learned the material that I need to know.”

- “Well, I have created a calendar since the beginning of class and it has really helped me with keeping up with my assignments.”

- “I feel that I am accomplishing my goals because I am understanding the materials and I feel that I could successfully apply the material in my own classroom.”

- “I know these [Types of assessment, motivation, and the differences between valid and reliable, and behaviorism] because I recalled them multiple times from my memory.

Pressley and his colleagues (Pressely, 1983; Pressely & Harris, 2006; Pressely & Hilden, 2006) emphasize the need for instructors, at all levels, to help students build their repertoire of strategies for learning. By the end of the course, many students feel they now have strategies for learning in any setting. Below are a few excerpts from students’ final submission on their goal monitoring sheets:

- “The most unusual thing about this class has been learning about learning. I am constantly thinking of how I am in these situations that we are studying.”

- “…we were taught new ways to take in work, and new strategies for studying and learning. I feel like these new tips were very useful as I achieved new things this semester.

References

Efklides, A. (2011). Interactions of metacognition with motivation and affect in self-regulated learning: The MASRL model. Educational Psychologist, 46(1), 6-25.

Hellman, C. (1996). Academic self-efficacy: Highlighting the first generation student. Journal of Applied Research in the Community College, 3, 69–75.

Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L. (2008). The critical importance of retrieval for learning. science, 319(5865), 966-968.

Nelson, T. O. (1996). Consciousness and metacognition. American Psychologist, 51(2), 102-116. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.51.2.102

Nelson, T. O., & Narens, L. ( 1994). Why investigate metacognition?. In J.Metcalfe & A.Shimamura ( Eds.), Metacognition: Knowing about knowing (pp. 1– 25). Cambridge, MA: Bradford Books.

Oettingen, G. (2014). Rethinking Positive Thinking: Inside the New Science of Motivation. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

Pressely, M. (1983). Making meaningful materials easier to learn. In M. Pressely & J.R. Levin (Eds.), Cognitive strategy research: Educational applications. NewYork: Springer-Verlag.

Pressley, M., & Harris, K.R. (2006). Cognitive strategies instruction; From basic research to classroom instruction. In P.A. Alexander & P.H. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (2nd ed). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Pressley, M., & Hilden, K. (2006). Cognitive strategies. In W. Damon & R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Roediger III, H. L., & Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in cognitive sciences, 15(1), 20-27.

Schunk, D. H. (1990). Goal setting and self-efficacy during self-regulated learning. Educational psychologist, 25(1), 71-86.

Tanner, K.D. (2012). Promoting Student Metacognition. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 11(2), 113-120. doi:10.1187/cbe.12

Metacognitive Skills and the Faculty

by Dave Westmoreland, U. S. Air Force Academy

While I applaud the strong focus on student development of metacognitive practices in this forum, I suspect that we might be overlooking an important obstacle to implementing the metacognitive development of our students – the faculty. Most faculty members are not trained how to facilitate the metacognitive development of students. In fact many are not aware of the need to help students develop metacognitive skills because explicit development of their own metacognitive skills didn’t occur to them when they were students.

I teach at a military institution in which the faculty is composed of about 60% military officers and 40% civilians. Since military faculty stay for three-year terms, there is an annual rotation in which about 20% of the entire faculty body is new to teaching. This large turn over poses an ongoing challenge for faculty development. Each year we have a week-long orientation for the new faculty, followed by a semester-long informal mentorship. Despite these great efforts, I believe that we need to do more when it comes to metacognition.

For example, in my department there is a strong emphasis on engaging students in the conceptual structure of science. As part of this training, we employ the exercise that I described in a previous blog (Science and Social Controversy – a Classroom Exercise in Metacognition”, 24 April 2014). With few exceptions, our new faculty, all of whom possess advanced degrees in science, struggle with the concepts as much as our undergraduates. It seems that the cognitive structure of science (the interrelation of facts, laws and theories) is not a standard part of graduate education. And without a faculty proficient in this concept, our goal of having students comprehend science as a way of knowing about the natural world will fail.

What is needed within faculty development is a more intentional focus on how faculty can develop their own metacognitive skills, and how they can support the metacognitive skill development of their students. A recent report by Academic Impressions reveals that, while virtually all institutions of higher education proclaim an emphasis on professional development, more than half of faculty perceive that emphasis to be little more than talk. Only ~ 42% of institutions give professional development a mission-critical status, and actively support professional development in their faculty and staff (Mrig, Fusch, & Cook, 2014). Highly effective institutions are proactive in directing professional development to meet emerging needs – perhaps this is where an emphasis on metacognition will take hold.

To that end, it is encouraging to see the initiative for a research study of metacognitive instruction on our own Improve with Metacognition site.

See https://www.improvewithmetacognition.com/researching-metacognition/ for the Call to Participate.

Reference

Mrig, A., Fusch, D, and Cook, P. 2014. The state of professional development in higher ed. http://www.academicimpressions.com/professional-development-md/?qq=29343o721616qY104

Self-Assessment, It’s A Good Thing To Do

by Stephen Fleisher, CSU Channel Islands

McMillan and Hearn (2008) stated persuasively that:

In the current era of standards-based education, student self-assessment stands alone in its promise of improved student motivation and engagement, and learning. Correctly implemented, student self-assessment can promote intrinsic motivation, internally controlled effort, a mastery goal orientation, and more meaningful learning (p. 40).

In her study of three meta-analyses of medical students’ self-assessment, Blanch-Hartigan (2011) reported that self-assessments did prove to be fairly accurate, as well as improving in later years of study. She noted that if we want to increase our understanding of self-assessment and facilitate its improvement, we need to attend to a few matters. To understand the causes of over- and underestimation, we need to address direction in our analyses (using paired comparisons) along with our correlational studies. We need also to examine key moderators affecting self-assessment accuracy, for instance “how students are being inaccurate and who is inaccurate” (p. 8). Further, the wording and alignment of our self-assessment questions in relation to the criteria and nature of our performance questions are essential to the accuracy of understanding these relationships.

When we establish strong and clear relationships between our self-assessment and performance questions for our students, we facilitate their use of metacognitive monitoring (self-assessment, and attunement to progress and achievement), metacognitive knowledge (understanding how their learning works and how to improve it), and metacognitive control (changing efforts, strategies or actions when required). As instructors, we can then also provide guidance when performance problems occur, reflecting on students’ applications and abilities with their metacognitive monitoring, knowledge, and control.

Self-Assessment and Self-Regulated Learning

For Pintrich (2000), self-regulating learners set goals, and activate prior cognitive and metacognitive knowledge. These goals then serve to establish criteria against which students can self-assess, self-monitor, and self-adjust their learning and learning efforts. In monitoring their learning process, skillful learners make judgments about how well they are learning the material, and eventually they become better able to predict future performance. These students can attune to discrepancies between their goals and their progress, and can make adjustments in learning strategies for memory, problem solving, and reasoning. Additionally, skillful learners tend to attribute low performance to low effort or ineffective use of learning strategies, whereas less skillful learners tend to attribute low performance to an over-generalized lack of ability or to extrinsic things like teacher ability or unfair exams. The importance of the more adaptive attributions of the aforementioned skillful learners is that these points of view are associated with deeper learning rather than surface learning, positive affective experiences, improved self-efficacy, and greater persistence.

Regarding motivational and affective experiences, self-regulating learners adjust their motivational beliefs in relation to their values and interests. Engagement improves when students are interested in and value the course material. Importantly, student motivational beliefs are set in motion early in the learning process, and it is here that instructional skills are most valuable. Regarding self-regulation of behavior, skillful learners see themselves as in charge of their time, tasks, and attention. They know their choices, they self-initiate their actions and efforts, and they know how and when to delay gratification. As well, these learners are inclined to choose challenging tasks rather than avoid them, and they know how to persist (Pintrich, 2000).

McMillan and Hearn (2008) summarize the role and importance of self-assessment:

When students set goals that aid their improved understanding, and then identify criteria, self-evaluate their progress toward learning, reflect on their learning, and generate strategies for more learning, they will show improved performance with meaningful motivation. Surely, those steps will accomplish two important goals—improved student self-efficacy and confidence to learn—as well as high scores on accountability tests (p. 48).

As a teacher, I see one of my objectives being to discover ways to encourage the development of these intellectual tools and methods of thinking in my own students. For example, in one of my most successful courses, a colleague and I worked at great length to create a full set of specific course learning outcomes (several per chapter, plus competencies we cared about personally, for instance, life-long learning). These course outcomes were all established and set into alignment with the published student learning outcomes for the course. Lastly, homework, lectures, class activities, individual and group assignments, plus formative and summative assessments were created and aligned. By the end of this course, students not only have gained knowledge about psychology, but tend to be pleasantly surprised to have learned about their own learning.

References

Blanch-Hartigan, D. (2011). Medical students’ self-assessment of performance: Results from three meta-analyses. Patient Education and Counseling, 84, 3-9.

McMillan, J. H., & Hearn, J. (2008). Student self-assessment: The key to stronger student motivation and higher achievement. Educational Horizons, 87(1), 40-49. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ815370.pdf

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.) Handbook of self-regulation. San Diego, CA: Academic.

Meta-Studying Video

This is a very good video by Elizabeth Yost from Xavier University about how to teach metacognitive skills in the higher education classroom.

http://youtu.be/Tr37GOSEukw?list=PLxf85IzktYWJH0behJ-ZQeZnsUQGzvFFf

Evidence for metacognition as executive functioning

by Kristen Chorba, PhD and Christopher Was, PhD, Kent State University

Several authors have noted that metacognition and executive functioning are descriptive of a similar phenomenon (see Fernandez-Duque, et al., 2000; Flavell, 1987; Livingston, 2003; Shimamura, 2000; Souchay & Insingrini, 2004). Many similarities can be seen between these two constructs: both regulate and evaluate cognitions, both are employed in problem solving, both are required for voluntary actions (as opposed to automatic responses), and more. Fernandez-Duque, et al. (2000) suggest that, despite their similarities, these two areas have not been explored together because of a divide between metacognitive researchers and cognitive neuroscientists; the metacognitive researchers have looked exclusively at metacognition, focusing on issues related to its development in children and its implications for education. They have preferred to conduct experiments in naturalistic settings, as a way to maximize the possibility that any information gained could have practical applications. Cognitive neuroscientists, on the other hand, have explored executive functioning using neuroimaging techniques, with the goal of linking them to brain structures. In the metacognitive literature, it has been noted metacognition occurs in the frontal cortex; this hypothesis has been evaluated in patients with memory disorders, and studies have noted that patients with frontal lobe damage, including some patients with amnesia, had difficulties performing metacognitive functions, including FOK judgments (Fernandez-Duque, et al., 2000; Janowsky, Shimamura, & Squire, 1989; Shimamura & Squire, 1986; as cited in Shimamura, 2000). Additionally, source monitoring and information retrieval has also been linked with the frontal cortex; source monitoring is an important metacognitive judgment (Shimamura, 2000). As previously stated, executive functions seem to be located generally in the frontal lobes, as well as specifically in other areas of the brain, contributing to the growing body of literature indicating that executive functions are both correlated and function independently. To explore the link between executive functioning and metacognition, Souchay and Isingrini (2004) carried out an experiment in which subjects were first asked to make evaluations on their own metacognition; they were then given a series of neurological tests to assess their executive functioning. They not only found a “significant partial correlation between metamemory control and executive functioning” (p. 89) but, after performing a hierarchical regression analysis, found that “age-related decline in metamemory control may be largely the result of executive limitations associated with aging” (p. 89).

As it relates to executive functioning, Fernandez-Duque, et al. (2008) noted that “the executive system modulates lower level schemas according to the subject’s intentions . . . [and that] without executive control, information processing loses flexibility and becomes increasingly bound to the external stimulus” (p. 289). These authors use the terms executive function and metacognition as essentially interchangeable, and note that these functions enable humans to “guide actions” where preestablished schema are not present and allow the individual to make decisions, select appropriate strategies, and successfully complete a task. Additionally, the primary task of both metacognition and executive functions are top-down strategies, which inform the lower level (i.e.: in metacognition, the object level; in executive functioning, as the construct which controls the “selection, activation, and manipulation of information in working memory” [Shimamura, 2000, p. 315]). Reviewing the similarities between metacognition and executive function, it seems that they are highly correlated constructs and perhaps share certain functions.

Executive functions and metacognition, while exhibiting similar functions and characteristics have, largely, been investigated along separate lines of research. Metacognitive research has focused on application and informing the teaching and learning processes. Executive functions, on the other hand, have primarily been researched as they relate to structures and locations within the brain. Recent literature and research indicates that executive functions and metacognition may be largely the same process.

References

Baddeley, A. (2005). Human Memory: Theory and Practice, Revised Edition. United Kingdom; Bath Press.

Blavier, A., Rouy, E., Nyssen, A., & DeKeyster, V. (2005). Prospective issues for error detection. Ergonomics, 7(10), 758-781.

Dinsmore, D., Alexander, P., & Loughlin, S. (2008). Focusing the conceptual lens on metacognition, self-regulation, and self-regulated learning. Educational psychology review, 20(4), 391-409.

Dunlosky, J., Metcalfe, J. (2008). Metacognition. Los Angeles: Sage.

Fernandez-Duque, D., Baird, J., Posner, M. (2000). Executive attention and metacognitive regulation. Consciousness and Cognition, 9, 288-307.

Flavell, J. (1987). Speculations about the nature and development of metacognition. In F. Weinert and R. H. Kluwe, (Eds.) Metacognition, Motivation, and Understanding. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Friedman, N. P., Haberstick, B. C., Willcutt, E. G., Miyake, A., Young, S. E., Corley, R. P., & Hweitt, J. K. (2007). Greater attention problems during childhood predict poorer executive functioning in late adolescence. Psychological Science, 18(10), 893-900.

Friedman, N. P., Miyake, A., Young, S. E., DeFries, J. C., Corley, R. P., Hewitt, J. K. (2008). Individual differences in executive functions are almost entirely genetic in origin. Journal of Experimental Psychology, General, 137(2), 201-225.

Friedman, N. P., Miyake, Corley, R. P., Young, S. E., DeFries, J. C., & Hewitt, J. K. (2006). Not all executive functions are related to intelligence. Psychological Science, 17(2), 172-179.

Georghiades, P. (2004). From the general to the situated: Three decades of metacognition. research report. International Journal of Science Education, 26(3), 365-383.

Higham, P. A. & Gerrard, C. (2005). Not all errors are created equal: Metacognition and changing answers on multiple-choice tests. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology, 59(1), 28-34.

Keith, N. & Frese, M. (2005) Self-regulation in error management training: Emotion control and metacognition as mediators of performance effects. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(4), 677-691.

Keith, N. & Frese, M. (2008). Effects of error management training: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 59-69.

Lajoie, S. (2008). Metacognition, self regulation, and self-regulated learning: A rose by any other name? Educational Psychology Review, 20(4), 469-475.

Livingston, J. A. (2003). Metacognition: An overview. Online ERIC Submission.

Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., & Howenter, A. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41, 49-100.

Nelson, T. O., & Narens, L. (1990). Metamemory: A theoretical framework and new

findings. In G. H. Bower (Ed.), The Psychology of Learning and Knowing. Cambridge, MIT Press, p. 1-26.

PP, N. (2008). Cognitions about cognitions: The theory of metacognition. Online ERIC Submission.

Shimamura, A. (2000). Toward a cognitive neuroscience of metacognition. Consciousness and Cognition, 9, 313-323.

Souchay, C., & Isingrini, M. (2004). Age related differences in metacognitive control: Role of executive functioning. Science Direct. 56(1), 89-99.

Thiede, K. W., & Dunlosky, J. (1994). Delaying students’ metacognitive monitoring improves their accuracy in predicting their recognition performance. Journal of educational psychology, 86(2), 290-302.

Winne, P. H., & Hadwin, A. F. (1998). Studying as self-regulated learning. In D. J. Hacker, J., Dunlosky, & A. Graessser (Eds.), Metacognition in educational theory and practice, (p. 277-304). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Self-assessment and the Affective Quality of Metacognition: Part 2 of 2

Ed Nuhfer, Retired Professor of Geology and Director of Faculty Development and Director of Educational Assessment, enuhfer@earthlink.net, 208-241-5029

In Part 1, we noted that knowledge surveys query individuals to self-assess their abilities to respond to about one hundred to two hundred challenges forthcoming in a course by rating their present ability to meet each challenge. An example can reveal how the writing of knowledge survey items is similar to the authoring of assessable Student Learning Outcomes (SLOs). A knowledge survey item example is:

I can employ examples to illustrate key differences between the ways of knowing of science and of technology.

In contrast, SLOs are written to be preceded by the phrase: “Students will be able to…,” Further, the knowledge survey items always solicit engaged responses that are observable. Well-written knowledge survey items exhibit two parts: one affective, the other cognitive. The cognitive portion communicates the nature of an observable challenge and the affective component solicits expression of felt confidence in the claim, “I can….” To be meaningful, readers must explicitly understand the nature of the challenges. Broad statements such as: “I understand science” or “I can think logically” are not sufficiently explicit. Each response to a knowledge survey item offers a metacognitive self-assessment expressed as an affective feeling of self-assessed competency specific to the cognitive challenge delivered by the item.

Self-Assessed Competency and Direct Measures of Competency

Three competing hypotheses exist regarding self-assessed competency relationship to actual performance. One asserts that self-assessed competency is nothing more than random “noise” (https://www.koriosbook.com/read-file/using-student-learning-as-a-measure-of-quality-in-hcm-strategists-pdf-3082500/; http://stephenporter.org/surveys/Self%20reported%20learning%20gains%20ResHE%202013.pdf). Two others allow that self-assessment is measurable. When compared with actual performance, one hypothesis maintains that people typically overrate their abilities and generally are “unskilled and unaware of it” (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2702783/). The other, “blind insight” hypothesis, indicates the opposite: a positive relationship exists between confidence and judgment accuracy (http://pss.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/11/11/0956797614553944).

Suitable resolution of the three requires data acquired from paired instruments of known reliability and validity. Both instruments must be highly aligned to collect data that addresses the same learning construct. The Science Literacy Concept Inventory (SLCI), a 25-item test tested on over 17,000 participants, produces data on competency with Cronbach Alpha Reliability .84, and possesses content, construct, criterion, concurrent, and discriminant validity. Participants (N=1154) who took the SLCI also took a knowledge survey (KS-SLCI with Cronbach Alpha Reliability of .93) that produced a self-assessment measure based on the identical 25 SLCI items. The two instruments are reliable and tightly aligned.

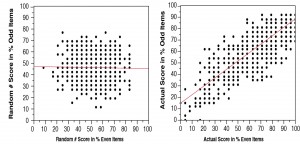

If knowledge surveys register random noise, then data furnished from human subjects will differ little from data generated with random numbers. Figure 1 reveals that data simulated from random numbers 0, 1, and 2 yield zero reliability, but real data consistently show reliability measures greater than R = .9 (Figure 1). Whatever quality(ies) knowledge surveys register is not “random noise.” Each person’s self-assessment score is consistent and characteristic.

Figure 1. Split-halves reliabilities of 25-item KS-SLCI knowledge surveys produced by 1154 random numbers (left) and by 1154 actual respondents (right).

Correlation between the 1154 actual performances on the SLCI and the self-assessed competencies through the KS-SLCI is a highly significant r = 0.62. Of the 1154 participants, 41.1% demonstrated good ability to self-assess their actual abilities to perform within ±10%, 25.1% of participants proved to be under-estimators, and 33.8% were over-estimators.

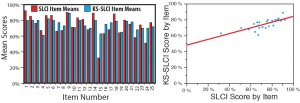

Because each of the 25 SLCI items poses challenges of varying difficulty, we could also test whether participants’ self-assessments gleaned from the knowledge survey did or did not show a relationship to the actual difficulty of items as reflected by how well participants scored on each of them. The collective self-assessments of participants revealed an almost uncanny ability to reflect the actual performance of the group on most of the twenty-five items (Figure 2), thus supporting the “blind insight” hypothesis. Knowledge surveys appear to register meaningful metacognitive measures, and results from reliable, aligned instruments reveal that people do generally understand their degree of competency.

Figure 2. 1154 participants’ average scores on each of 25 SLCI items correspond well (r = 0.76) to their average scores predicted by knowledge survey self-assessments.

Advice in Using Knowledge Surveys to Develop Metacognition

- In developing competency in metadisciplinary ways of knowing, furnish a bank of numerous explicit knowledge survey items that scaffold novices into considering the criteria that experts consider to distinguish a specific way of knowing from other ways of thinking.

- Keep students in constant contact with self-assessing by redirecting them repeatedly to specific blocks of knowledge survey items relevant to tests and other evaluations and engaging them in debriefings that compare their self-assessments with performance.

- Assign students in pairs to do short class presentations that address specific knowledge-survey items while having the class members monitor their evolving feelings of confidence to address the items.

- Use the final minutes of the class period to enlist students in teams in creating alternative knowledge survey items that address the content covered by the day’s lesson.

- Teach students the Bloom Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain (http://orgs.bloomu.edu/tale/documents/Bloomswheelforactivestudentlearning.pdf) so that they can recognize both the level of challenge and the feelings associated with constructing and addressing different levels of challenge.

Conclusion: Why use knowledge surveys?

- Their skillful use offers students many practices in metacognitive self-assessment over the entire course.

- They organize our courses in a way that offers full transparent disclosure.

- They convey our expectation standards to students before a course begins.

- They serve as an interactive study guide.

- They can help instructors enact instructional alignment.

- They might be the most reliable assessment measure we have.

The Stakes: “You’ve Been Mucking With My Mind”

by Craig Nelson Indiana University

Earlier on this blog site, Ed Nuhfer (2014, Part 1, Part 2) urged us to consider the fundamental importance of Perry’s book (1970, 1999) for understanding what we are trying to do in fostering critical thinking, metacognition and other higher order outcomes. I enthusiastically agree.

I read Perry’s book (1970) shortly after it was published. I had been teaching at IU for about five years and had seen how difficult it was to effectively foster critical thinking, even in college seniors. Perry’s book transformed my thinking and my teaching. I realized that much of my own thinking was still essentially what he might have called sophomoric. I had to decide if I was convinced enough to fundamentally change how I thought. Once I began to come to grips with that I saw that Perry’s synthesis of his students’ experiences really mattered for teaching.

Perry made clear that there were qualitatively very different ways to think. Some of these ways included what I had been trying to get my students to master as critical thinking. But Perry helped me understand more explicitly what that might mean. More importantly, perhaps, he also helped me understand how to conceptualize the limits of my approach and what kinds of critical thinking the students would need to master next if I were to be successful. At the deepest level Perry helped me see that the issues were not only how to think in sophisticated ways. The real problems are more in the barriers and costs to thinking in more sophisticated ways.

And so I began. For about five years I taught in fundamentally new ways, challenging the students’ current modes of thinking and trying to address the existential barriers to change (Nelson 1989, 1999). I then decided that perhaps I should let the students more fully in on what I was doing. I thought it might be helpful to have them actually read excepts from Perry’s book. This was a challenging thought. I was teaching a capstone course for biology majors. Perry’s “Forms of Intellectual And Ethical Development, A Scheme” was rather clearly not the usual fare for such a course. So I decided to introduce it about halfway into the course, after the students had been working within a course framework designed to foster a deep understanding of scientific thinking.

I had incorporated a full period discussion each week for which the students prepared a multiple-page worksheet analyzing a reading assignment (See the Red Pen Worksheet; Nelson 2009, 2010a). Most of the students responded very positively to Perry as a discussion assignment (Perry Discussion Assignment1; Perry Selected Passages; Ingram and Nelson 2006, 2009).

For the final discussion at the end of the course, one of the questions was approximately: “Science is always changing. I will want to introduce new readings next time. Of the ones we read, which three should I consider replacing and why, and which three should I most certainly keep and why?” Perry was the reading most frequently cited as among the “most certainly keep.” Indeed, reactions were so strongly positive that comments even included: “I personally got little from Perry but the others in my group found it so valuable that you have to keep it.”

One subsequent year I assigned Perry on a Tuesday to be read for the discussion period scheduled the next week. The next morning I arrived at my office at 8 am. One of my students was sitting outside my office on the floor. I greeted her by name and asked if she was waiting to talk to me. “Why, yes.” (She skipped “duh.” Note that we are into seriously deviant behavior here: residential campus at 8 am, no appointment, no reason to think I would be there at that time.) After a few pleasantries she announced: “I read Perry last night.” (Deviance was getting thicker: She had read the assignment immediately and a week before it was due!) “I finally understand what you are trying to do in this course, and I really like it.” (This was a fairly common reaction as Perry provided a metacognitive framework that allowed the students to more deeply understand the purpose of the assignments we had been doing2.) “And I liked Perry a lot, too.” (I am thinking: it is 8 am, she can’t be here simply to rave about an assignment.) “But, I am a bit mad at you. You have been mucking3 with my mind. College courses don’t do that! I haven’t had a course muck with my mind since high school. And, I just wanted to say that you should have warned me!” (She was a college senior.) I agreed that I should have warned her and apologized. She seemed satisfied with this and we parted on good terms.

However, I was not satisfied with this state of affairs. She had felt violated by my trying to foster changes in how she thought. And I guessed that many of my other students probably had felt at least twinges of the same feelings. This led me to ask myself: “What is the difference between indoctrination and meaningful but fair education.” I concluded that fair educational practice would require trying to make the agenda public and understood before trying to change students’ minds. This openness would require more than just assigning a reading in the middle of the semester. Thereafter, I always included a non-technical summary of Perry in my first day classes (as in Nelson 2010 b) and usually assigned Perry as the second discussion reading, having used the first discussion to start mastering the whole-period discussion process.

I would generalize my conclusion here. We instructors (almost?) always need to keep students aware of our highest-level objectives in order to avoid indoctrination rather than fair education. Fortunately, I think that this approach also will often facilitate student mastery of these objectives. It is nice when right seems to match effective, eh?

1I decided somewhat reluctantly to include the details of this assignment. I strongly suggest that you read this short book and select the pages and passages that seem most relevant to the students and topics that you are teaching.

2Students find it especially easy to connect with Perry’s writing. He includes numerous direct quotations from interviews with students.

3She used a different initial letter in “mucking,” as you may have expected.

————-

Ingram, Ella L. & Craig E. Nelson. 2006. Relationship between achievement and students’ acceptance of evolution or creation in an upper-level evolution course. Journal of Research in Science Teaching 43:7-24.

Ingram, Ella L. & Craig E. Nelson. 2009. Applications of intellectual development theory to science and engineering education. P 1-30 in Gerald F. Ollington (Editor), Teachers and Teaching: Strategies, Innovations and Problem Solving. Nova Science Publishers.

Nelson, Craig E. (1986). Creation, evolution, or both? A multiple model approach. P 128–159 in Robert W. Hanson (Editor), Science and Creation: Geological, Theological, and Educational Perspectives New York: MacMillan.

Nelson, Craig E. (1989). Skewered on the unicorn’s horn: The illusion of a tragic tradeoff between content and critical thinking in the teaching of science. P 17–27 in Linda Crowe (Editor), Enhancing Critical Thinking in the Sciences. Washington, DC: Society of College Science Teachers.

Nelson, Craig E. (1999). On the persistence of unicorns: The tradeoff between content and critical thinking revisited. P 168–184 in Bernice A. Pescosolido & Ronald Aminzade (Editors), The Social Worlds of Higher Education: Handbook for Teaching in a New Century. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Nelson, Craig E. 2009. The “Red Pen” Worksheet. Quick Start Series. Center for Excellence in Learning & Teaching. Humboldt State University. 2 pp. [Edited excerpt from Nelson 2010 a.]

Nelson, Craig E. (2010 a). Want brighter, harder working students? Change pedagogies!

Examples from biology. P 119–140 in Barbara J. Millis (Editor), Cooperative Learning in Higher Education: Across the Disciplines, Across the Academy. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Nelson, Craig E. 2010. Effective Education for Environmental Literacy. P 117-129 in Heather L. Reynolds, Eduardo S. Brondizio, and Jennifer Meta Robinson with Doug Karpa and Briana L. Gross (Editors). Teaching Environmental Literacy in Higher Education: Across Campus and Across the Curriculum. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Nelson, Craig E. 2012. Why Don’t Undergraduates Really ‘Get’ Evolution? What Can Faculty Do? P 311-347 in Karl S. Rosengren, Sarah K. Brem, E. Margaret Evans, & Gale M. Sinatra (Editors.) Evolution Challenges: Integrating Research and Practice in Teaching and Learning about Evolution. Oxford University Press.

Nuhfer, Ed. (2104a). Metacognition for guiding students to awareness of higher-level thinking (part 1). Retrieved from https://www.improvewithmetacognition.com/metacognition-for-guiding-students-to-awareness-of-higher-level-thinking-part-1/

Nuhfer, Ed. (2104b). Metacognition for guiding students to awareness of higher-level thinking (part 2). Retrieved from https://www.improvewithmetacognition.com/metacognition-for-guiding-students-to-awareness-of-higher-level-thinking-part-2/

Perry, William G., Jr. (1970). Forms of Intellectual and Ethical Development in the College Years: A Scheme. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Perry, William G., Jr. (1999). Forms of Ethical and Intellectual Development in the College Years: A Scheme. (Reprint of the 1968 1st edition with a new introduction by Lee Knefelkamp). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.