by Arthur L. Costa, Ed. D. (Professor Emeritus, California State University, Sacramento). This paper summarizes 16 attributes of what human beings do when they behave intelligently, referred to as Habits of Mind. Metacognition is the 5th mentioned (see a nice summary of all 16 on the final page). Dr. Costa points out that these “Habits of Mind transcend all subject matters commonly taught in school. They are characteristic of peak performers whether they are in homes, schools, athletic fields,organizations, the military, governments, churches or corporations.”

Month: June 2015

Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Reflection, Anyone?

By Cynthia Desrochers, California State University Northridge

I once joked with my then university president that I’d seen more faculty teach in their classrooms than she had. She nodded in agreement. I should have added that I’d seen more than the AVP for Faculty Affairs, all personnel committees, deans, or chairpersons. For some reason, university teaching is done behind closed doors, no peering in on peers unless for personnel reviews. We attempted to change that at CSU Northridge when I directed their faculty development center from 1996-2005. Our Faculty Reciprocal Peer Coaching program typically drew a dozen or more cross-college dyads over the dozen semesters it was in existence. The program’s main goal was teacher self-reflection.

I believe I first saw the term peer coaching when reading a short publication by Joyce and Showers (1983). What stuck me was their assertion that to have any new complex teaching innovation become part of one’s teaching repertoire required four steps: 1) understanding the theory/knowledge base undergirding the innovation, 2) observing an expert who is modeling how to do the innovation, 3) practicing the innovation in a controlled setting with coaching (e.g., micro-teaching in a workshop) and 4) practicing the innovation in one’s own classroom with coaching. They maintained that without all four steps, the innovation taught in a workshop would likely not be implemented in the classroom. Having spent much of my life teaching workshops about using teaching innovations, these steps became my guide, and I still use them today. In addition, after many years of coaching student teachers at UCLA’s Lab School, I realized that they were more likely to apply teaching alternatives that they identified and reflected upon in the post-conference than ones that I singled out. That is, they learned more from using metacognitive practices than from my direct instruction, so I began formulating some of the thoughts summarized below.

Fast forward many years to this past year, where I co-facilitated a yearlong eight-member Faculty Learning Community (FLC) focused on implementing the following Five Gears for Activating Learning: Motivating Learning, Organizing Knowledge, Connecting Prior Knowledge, Practicing with Feedback, and Developing Mastery [see previous blog]. With this FLC, we resurrected peer coaching on a voluntary basis in order to promote conscious use of the Five Gears in teaching. All eight FLC members not only volunteered to pair up for reciprocal coaching of one another, but they were eager to do so.

I was asked by one faculty member why is it called coaching, because an athletic coach often tells players what to do, versus helping them self-reflect. I responded that it’s because Joyce and Showers’ study looked at the research on training athletes and what that required for skill transfer. They showed the need for many practice sessions combined with coaching in order to achieve mastery of any new complex move, be it on the playing field or in the classroom. However, their point of confusion was noted, so now I refer to the process as Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Reflection. This reflective type of peer coaching applies to cross-college faculty dyads who are seeking to more readily apply a new teaching innovation.

Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Refection applies all or some of the five phases of the Clinical Supervision model described by Goldhammer(1969), which include: pre-observation conference, observation and data collection, data analysis and strategy, post-observation conference, and post-conference analysis. However, it is in the post-conference phase where much of the teacher self-reflection occurs and where the coach can benefit from an understanding of post-conference messages.

Prior to turning our FLC members loose to peer coach, we held a practicum on how to do it. And true to my statement above, I applied Joyce and Showers’ first three steps in our practicum (i.e., I explained the theory behind peer coaching, modeled peer coaching, and then provided micro-practice of a videotaped lesson taught by one of our FLC members). But in the micro-practice, right out of the gate, faculty coaches began telling the teacher how she used the Five Gears versus prompting her to reflect upon her own use first. Although I gently provided feedback in an attempt to redirect the post-conferences from telling to asking, it was a reminder of how firmly ingrained this default position has become with faculty, where the person observing a lesson takes charge and provides all the answers when conducting the post-conference. The reasons for this may include 1)prior practice as supervisors who are typically charged with this role, 2) the need to show their analytic prowess, or 3) the desire to give the teacher a break from doing all the talking. Whatever the reason, we want the teacher doing the reflective analysis of her own teaching and growing those dendrites as a result.

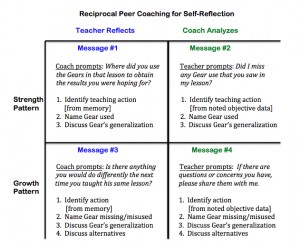

After this experience with our FLC, I crafted the conference-message matrix below and included conversation-starter prompts. Granted, I may have over-simplified the process, but it illustrates key elements for promoting Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Reflection. Note that the matrix is arranged into four types of conference messages: successful and unsuccessful teaching-learning situations, where the teacher identifies the topic of conversation after being prompted by the coach (messages #1 and #3) and successful and unsuccessful teaching-learning situations, where the coach identifies the topic of conversation after being prompted by the teacher (messages #2 and #4). The goal of Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Reflection is best achieved when the balance of the post-conference contains teacher self-reflection; hence, messages #1 and #3 should dominate the total post-conference conversation. Although the order of messages #1 through #4 is a judgment call, starting with message #1permits the teacher to take the lead in identifying and reflecting upon her conscious use of the Gears and their outcome –using her metacognition—versus listening passively to the coach. An exception to beginning with message #1 may be that the teacher is too timid to sing her own praises, and in this instance the coach may begin with message #2 when this reluctance becomes apparent. Note further that this model puts the teacher squarely in the driver’s seat throughout the entire post-conference; this is particularly important when it comes to message #4, which is often a sensitive discussion of unsuccessful teaching practices. If the teacher doesn’t want another’s critique at this time, she is told not to initiate message #4, and the coach is cautioned to abide this decision.

The numbered points under each of the four types of messages are useful components for discussion during each message in order to further cement an understanding of which Gear is being used and its value for promoting student learning: 1) Identifying the teaching action from the specific objective data collected by the coach (e.g., written, video, or audio) helps to isolate the cause-effect teaching episode under discussion and its effect on student learning. 2) Naming the Gear (or naming any term associated with the innovating being practiced) increases our in-common teaching vocabulary, which is considered useful for any profession. 3) Discussing the generalization about how the Gear helps students learn reiterates its purpose, fostering motivation to use it appropriately. And 4) crafting together alternative teaching-learning practices for next time expands the teacher’s repertoire.

The FLC faculty reported that their classroom Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Reflection sessions were a success. Specifically, they indicated that they used the Five Gears more consciously after discussing them during the post-conference; that the Five Gears were beginning to become part of their teaching vocabulary; and that they were using the Five Gears more automatically during instruction. Moreover, unique to message #2, it provided the benefit of having one’s coach identify a teacher’s unconscious use of the Five Gears, increasing the teacher’s awareness of themselves as learners of an innovation, all of which serve to increase metacognition.

When reflecting upon how we might assist faculty in implementing the most promising research-based teaching-learning innovations, I see a system where every few years we allot reassigned time for faculty to engage in Reciprocal Peer Coaching for Self-Reflection.

References

Goldhammer, R. (1969). Clinical supervision. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Joyce, B. & Showers, B. (1983). Power in staff development though research on training. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

To Test or Not to Test: That is the Metacognitive Question

by John Schumacher & Roman Taraban at Texas Tech University

In prepping for upcoming classes, we are typically interested in how to best structure the class to promote the most effective learning. Applying best-practices recommendations in the literature, we try to implement active learning strategies that go beyond simple lecturing. One such strategy that has been found to be effective from research is the use of testing. The inference to draw from the research literature is quite simple: test students frequently, informally, and creatively, over and above standard course tests, like a mid-term and final. Testing is a useful assessment tool, but research has shown that it is also a learning tool that has been found to promote learning above and beyond simply rereading material (Roediger & Karpicke, 2006a). This is called the testing effect. In controlled studies, researchers have shown testing effects with a variety of materials, including expository texts and multimedia presentations (e.g., Carrier & Pashler, 1992; Huff, Davis, & Meade, 2013; Johnson & Mayer, 2009; Roediger & Karpicke, 2006b). Testing has been found to increase learning when implemented in a classroom setting (McDaniel, Anderson, Derbish, & Morrisette, 2007) and is a useful learning tool for people of all ages (Meyer & Logan, 2013). The theoretical explanation for the benefits of testing is that testing strengthens retrieval paths to the stored information in memory more so than simply rereading the material. Therefore, later on a person can more effectively recover the information from memory.

Although implementing testing and other active learning strategies in the classroom is useful in guiding and scaffolding student learning, it is important that we develop an understanding of when and for whom these strategies are most helpful. Specifically, regarding testing, research from our lab and in others is starting to show that testing may not always be as beneficial as past research suggests. Characteristics of the students themselves may nullify or even reverse the benefits of testing. Thus, the first question we address is whether frequent classroom testing will benefit all students. Yet a more pertinent question, which is our second question, is whether frequent testing develops metacognitive practices in students. We will discuss these in turn.

In a formal study of the testing effect, or in an informal test in any classroom, one needs two conditions, a control condition in which participants study the material on their own for a fixed amount of time, and an experimental condition in which participants study and are tested over the material, for instance, in a Study-Test-Study-Test format. Both groups spend an equal amount of time either simply studying or studying and testing. All participants take a final recall test over the material. Through a series of testing-effect studies incorporating expository texts as the learning material, we have produced a consistent grade-point average (GPA) by testing-effect interaction. This means that the benefits of testing (i.e., better later retrieval of information) depend on students’ GPAs! A closer look at this interaction showed us that students with low GPAs benefited most from the implementation of testing whereas mid to high GPA students benefited just as much by simply studying the material.

While at this preliminary stage it is difficult to ascertain why exactly low GPA students benefit from testing in our experiments while others do not, a few observations can be put forth. First, at the end of the experiments, we asked participants to report any strategies they used on their own to help them learn the materials. Metacognitive reading strategies that the participants reported included focusing on specific aspects of the material, segmenting the material into chunks, elaborating on the material, and testing themselves. Second, looking further into the students’ self-reports of metacognitive strategy use, we found that participants in the medium to high GPA range used these strategies often, while low GPA students used them less often. Simply, the self-regulated use of metacognitive strategies was associated with higher GPAs and better recall of the information in the texts that the participants studied. Lower GPA students benefited when the instructor deliberately imposed self-testing.

These results are interesting because they indicate that the classroom implementation of testing may only be beneficial to low achieving students because they either do not have metacognitive strategies at their disposal or are not applying these strategies. High-achieving students may have metacognitive strategies at their disposal and may not need that extra guidance set in place by the instructor.

Another explanation for the GPA and testing-effect interaction may simply be motivation. Researchers have found that GPA correlates with motivation (Mitchell, 1992). It is possible that implementing a learning strategy may be beneficial to low GPA students because it forces them to work with the material. Motivation may also explain why GPA correlated with metacognitive strategy use. Specifically if lower GPA students are less motivated to work with the material it stands to reason that they would be less likely to employ learning strategies that take time and effort.

This leads to our second question: Does frequent testing develop metacognitive skills in students, particularly self-regulated self-testing? This is a puzzle that we cannot answer from the current studies. Higher-GPA students appear to understand the benefits of applying metacognitive strategies and do not appear to need additional coaxing from the experimenter/teacher to apply them. Will imposing self-testing, or any other strategy on lower-GPA students lead them to eventually adopt the use of these strategies on their own? This is an important question and one that deserves future attention.

While testing may be useful for bolstering learning, we suggest that it should not be blindly utilized in the classroom as a learning tool. A consideration of what is being taught and to whom will dictate the effectiveness of testing as a learning tool. As we have suggested, more research also needs to be done to figure out how to bring metacognitive strategies into students’ study behaviors, particularly low-GPA students.

References

Carrier, M., & Pashler, H. (1992). The influence of retrieval on retention. Memory & Cognition, 20(6), 633-642.

Huff, M. J., Davis, S. D., & Meade, M. L. (2013). The effects of initial testing on false recall and false recognition in the social contagion of memory paradigm. Memory & Cognition, 41(6), 820-831.

Johnson, C. I., & Mayer, R. E. (2009). A testing effect with multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(3), 621-629.

McDaniel, M. A., Anderson, J. L., Derbish, M. H., & Morrisette, N. (2007). Testing the testing effect in the classroom. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19(4-5), 494-513.

Meyer, A. D., & Logan, J. M. (2013). Taking the testing effect beyond the college freshman: Benefits for lifelong learning. Psychology and Aging, 28(1), 142-147.

Mitchell Jr, J. V. (1992). Interrelationships and predictive efficacy for indices of intrinsic, extrinsic, and self-assessed motivation for learning. Journal of Research and Development in Education, 25(3), 149-155.

Roediger, H., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006a). The power of testing memory: Basic research and implications for educational practice. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1(3), 181- 210.

Roediger, H., & Karpicke, J. D. (2006b). Test-enhanced learning: Taking memory tests improves long-term retention. Psychological Science, 17(3), 249-255.

Positive Affective Environments and Self-Regulation

by Steven Fleisher at CSU Channel Islands

Although challenging at times, providing for positive affective experiences are necessary for student metacognitive and self-regulated learning. In a classroom, caring environments are established when teachers not only provide structure, but also attune to the needs and concerns of their students. As such, effective teachers establish those environments of safety and trust, as opposed to merely environments of compliance (Fleisher, 2006). When trust is experienced, learning is facilitated through the mechanisms of autonomy support as students discover how the academic information best suits their needs. In other words, students are supported in moving toward greater intrinsic (as opposed to extrinsic) motivation and self-regulation, and ultimately enhanced learning and success (Deci & Ryan, 2002; Pintrich, 2003).

Autonomy and Self-Regulation

In an academic context, autonomy refers to students knowing their choices and alternatives and self-initiating their efforts in relation to those alternatives. For Deci and Ryan (1985, 2002), a strong sense of autonomy within a particular academic task would be synonymous with being intrinsically motivated and, thus, intrinsically self-regulated. On the other hand, a low sense of autonomy within a particular academic context would be synonymous with being extrinsically motivated and self-regulated. Students with a low sense of autonomy might say, “You just want us to do what you want, it’s never about us,” while students with a strong sense of autonomy might say, “We can see how this information may be useful someday.” The non-autonomous students feel controlled, whereas the autonomous students know they are in charge of their choices and efforts.

Even more relevant to the classroom, Pintrich (2003) reported that the more intrinsically motivated students have mastery goal-orientations (a focus on effort and effective learning strategy use) as opposed to primarily performance goal-orientations (actually a focus on defending one’s ability). These two positions are best understood under conditions of failure. Performance-orientated students see failure as pointing out their innate inabilities, whereas mastery-oriented students see failure as an opportunity to reevaluate and reapply their efforts and strategies as they build their abilities. Thus, in the long run, mastery-oriented students end up “performing” the best academically.

The extrinsically motivated students perceive that the teacher is in charge, and not themselves, as to whether or not they are rewarded for their work. This extrinsic orientation may facilitate performance, however, it can backfire. These students can become unwilling to put forth a full effort for fear of failure or judgment. These students feel a compulsion for performance, which can result in a refusal to try to meet goals. They may come to prefer unchallenging courses, fail, or drop out entirely. On the other hand, students with intrinsic goal-orientations realize that they are in charge of their reasons for acting. Metacognitively, they are aware of their alternatives and strategies and self-regulate accordingly as they apply the necessary effort toward their learning tasks. These students would sense that the classroom provided an environment for exploring the subject matter in relevant and meaningful ways and they would identify how and where to best apply their learning efforts.

Strategies for the Classroom

As with autonomy (minimum to maximum), motivation and self-regulation exist on a continuum (extrinsic to intrinsic), as opposed to existing at one end or the other. Here are a couple of instructional strategies that I have found that support students in their movement toward greater autonomy and intrinsic motivation and self-regulation.

Knowledge surveys, for example, offer a course tool for organizing content learning and assessing student intellectual development (Nuhfer & Knipp, 2003). These surveys consist of questions that represent the breadth and depth of the course, including the main concepts, the related content information, and the different levels of reasoning to be practiced and assessed. I have found that using knowledge surveys to disclose to student where a course is going and why helps them take charge of their learning. This type of transparency helps students discover ways in which their learning efforts are effective.

Cooperative learning strategies (Millis & Cottell, 1998) provide an ideal counterpart to knowledge surveys. Cooperative learning (for instance, working in groups or teaching your neighbor) offers both positive learning and positive affective experiences. These learning experiences, between students and between teachers and students support the development of autonomy, as well as intrinsic motivation and self-regulation. For example, when students work together effectively in applications of course content, they come to see through one another’s perspectives the relevance of the material, while gaining competency as well as insights into how to gain that competency. When students are aware, by way of the knowledge surveys, of the course content and levels of reasoning required, and when these competencies and related learning strategies are practiced, reflected upon, and attained, learning and metacognitive learning are engaged.

References

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Press.

Deci, E. L. & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. Rochester, NY: The University of Rochester Press.

Fleisher, S. C. (2006). Intrinsic self-regulation in the classroom. Academic Exchange Quarterly, 10(4), 199-204.

Millis, B. J. & Cottell, P. G. (1998). Cooperative learning for higher education faculty. American Council on Education: Oryx Press.

Nuhfer, E. & Knipp, D. (2003). The knowledge survey: A tool for all reasons. To Improve the Academy, 21, 59-78.

Pintrich, P. R. (2003). Motivation and classroom learning. In W. M. Reynolds & G. E. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Educational psychology, Volume 7. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Using Just-in-Time assignments to promote metacognition

by John Draeger (SUNY Buffalo State)

In a previous post entitled “Just-in-time for metacognition,” I argued that Just-in-Time teaching techniques could be used to promote both higher-order-thinking and metacognition. Just-in-time teaching techniques require that students submit short assignments prior to class for review by the instructor before class begins (Novak 1999; Simkins & Maier, 2009; Schraff et al., 2011). In my philosophy courses, students send their answers to me electronically the night before class and I spend the morning of class using their answers to shape my pre-class planning. I’ve had success with higher-order-thinking questions, but I tended to ask students questions about their learning process only when the class had clearly gone off track. Since I’ve become convinced that developing good metacognitive habits requires practice, I’ve made metacognitive questions a regular component of my Just-in-Time assignments. In this post, I thought I would let you know how things are going.

Research shows that students learn more effectively when they are aware of their own learning process (I encourage you to surf around this site for examples). Borrowing from Tanner (2012) and Scharff (2014), I have asked students to think about why and how they engage in various learning strategies (e.g., reading, writing, reflecting). More specifically, I have asked: what was the most challenging part of the reading? Was the current reading more challenging than the last? What was the most useful piece of the reading? What was the most challenging piece of the reading? What was your reading strategy this week? How might you approach the reading differently next time? What was the most challenging part of the last writing assignment? How might you approach your next writing assignment differently? What are your learning goals for the week?

Responses from students at all levels have been remarkably similar. In particular, student responses fall into three broad categories: general student commentary (e.g., about the course, reading, particular assignment), content (e.g., students reframe the metacognition question and answer with use of course content), reflective practice (e.g., students actually reflect on their learning process).

First Type of Response: General Commentary

- When asked to describe the most challenging part of the reading, students took the opportunity to observe that the reading too long, too boring, or it was interesting but confusing.

- When asked to describe the most useful part of the reading, students often said that the question was difficult to answer because the reading was too long, too boring, or it was interesting but confusing.

- When asked about their reading strategy, students observed that they did their best but the reading was too long, too boring, or interesting but confusing.

- When asked about their learning goals for the week, students said that the question was strange, off the wall, and they had never been asked such a thing before.

Second Type of Response: Content

- When asked to describe the most challenging part of the reading, students identified particular examples that were hard to follow and claims that seemed dubious.

- When asked to describe the most useful part of the reading, students often restated the central question of the week (e.g., is prostitution morally permissible? should hate speech be restricted?) or summarized big issues (e.g., liberty argument for the permissibility of prostitution or hate speech).

- When asked about their reading strategy, students often said that they wanted to understand a particular argument for that day (e.g., abortion, euthanasia, prostitution).

- When asked their learning goal for the week, students said that they wanted to explore a big question (e.g., the nature of liberty or equality) and put philosophers into conversation (this is a major goal in all my courses).

Third Type of Response: Reflective practice

- When asked to describe the most challenging part of the reading, students said that they didn’t give themselves enough time, they stretched it over multiple days, or they didn’t do it at all.

- When asked about the most useful part of the reading, some students said that the reading forced them to challenge their own assumptions (e.g., “I always figured prostitution was disgusting, but maybe not”).

- When asked about their reading strategies, some said that they had to read the material several times. Some said they skimmed the reading and hoped they could piece it together in class. Others found writing short summaries to be essential.

- When asked about their learning goals for the week, some students reported wanting to become more open-minded and more tolerant of people with differing points of view.

Responses to the metacognitive prompts have been remarkably similar from students in my freshman to senior level courses. In contrast, I can say that there’s a marked difference by class year in responses to higher-order thinking prompts, possibly because I regularly use student responses to higher-order thinking prompts to structure class discussion. While I gave students some feedback on their metacognitive prompt responses, in the future I could be more intentional about using their responses to structure discussions of the student learning process.

I also need to refine my metacognition-related pre-class questions. For example, asking students to discuss the most challenging part of a reading assignment encourages students to reflect on roadblocks to understanding. The question is open-ended in a way that allows students to locate the difficulty in a particular bit of content, a lack of motivation, or a deficiency in reading strategy. However, if I want them to focus on their learning strategies, then I need to focus the question in ways that prompt that sort of reflection. For example, I could reword the prompt as follows: Identify one challenging passage in the reading this week. Explain why you believe it was difficult to understand. Discuss what learning strategy you used, how you know whether the strategy worked, and what you might do differently next time. Revising the questions so that they have a more explicitly metacognitive focus is especially important given that students are often unfamiliar with metacognitive reflection. If I can be more intentional about how I promote metacognition in my courses, then perhaps there can be gains in the metacognitive awareness demonstrated by my students. I’ll keep you posted.

References

Novak, G., Patterson, E., Gavrin, A., & Christian, W. (1999). Just-in-time teaching: Blending active learning with web technology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Scharff, L. “Incorporating Metacognitive Leadership Development in Class.” (2014). Retrieved from https://www.improvewithmetacognition.com/incorporating-metacognitive-leadership-development-in-class/.

Scharff, L., Rolf, J. Novotny, S. and Lee, R. (2011). “Factors impacting completion of pre-class assignments (JiTT) in Physics, Math, and Behavioral Sciences.” In C.

Rust (ed.), Improving Student Learning: Improving Student Learning Global Theories and Local Practices: Institutional, Disciplinary and Cultural Variations. Oxford Brookes University, UK.

Simkins, S. & Maier, M. (2009). Just-in-time teaching: Across the disciplines, across the academy. Stylus Publishing, LLC..

Tanner, K. D. (2012). Promoting student metacognition. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 11(2), 113-120.