by Tara Beziat at Auburn University at Montgomery

What are your goals for this semester? Have you written down your goals? Do you think your students have thought about their goals and written them down? Though these seem like simple tasks, we often do not ask our students to think about their goals for our class or for the semester. Yet, we know that a key to learning is planning, monitoring and evaluating one’s learning (Efklides, 2011; Nelson, 1996; Schraw and Dennison, 1994; Nelson & Narens, 1994). By helping our students engage in these metacognitive tasks, we are teaching them how to learn.

Over the past couple of semesters, I have asked my undergraduate educational psychology students to complete a goal-monitoring sheet so they can practice, planning, monitoring and evaluating their learning. Before we go over the goal-monitoring sheet, I explain the learning process and how a goal-monitoring sheet helps facilitate learning. We discuss how successful students set goals for their learning, monitor these goals and make necessary adjustments through the course of the semester (Schunk, 1990). Many first-generation students and first-time freshman come to college lacking self-efficacy in academics and one set back can make them feel like college is not for them (Hellman, 1996). As educators we need to help them understand we all make mistakes and sometimes fail, but we need to make adjustments based on those failures not quit.

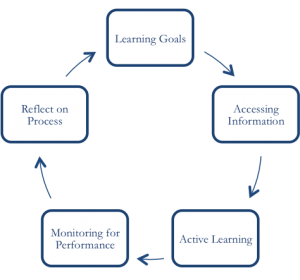

Second, I talk with my class about working memory, long-term memory, and how people access information in one of two ways: verbally or visually (Baddeley, 2000, 2007). Seeing and/or hearing the information does not make learning happen. As a student, they must take an active role and practice retrieving the information (Karpicke & Roediger, 2008; Roediger & Butler, 2011). Learning takes work. It is not a passive process. Finally, we discuss the need to gauge their progress and reflect on what is working and what is not working. On the sheet I reiterate what we have discussed with the following graphic:

After this brief introduction about learning, we talk about the goal-monitoring sheet, which is divided into four sections: Planning for Success, Monitoring your Progress, Continued Monitoring and Early Evaluation and Evaluating your Learning. Two resources that I used to make adjustments to the initial sheet were the questions in Tanner’s (2012) article on metacognition in the classroom and the work of Gabrielle Oettingen (2014). Oettigen points out that students need to consider possible obstacles to their learning and evaluate how they would handle them. Students can use the free WOOP (Wish, Outcome, Obstacle, Plan) app to “get through college.”

Using these resources and the feedback from previous students, I created a new goal-monitoring sheet. Below are the initial questions I ask students (for the full Goal Monitoring Sheet see the link at the bottom):

- What are your goals for this class?

- How will you monitor your progress?

- What strategies will you use to study and prepare for this class?

- When can you study/prepare for this class?

- Possible obstacles or areas of concern are:

- What resources can you use to achieve your goals?

- What do you want to be able to do by the end of this course?

Interestingly, many students do not list me, the professor as a resource. I make sure to let the students know that I am available and should be considered a resource for the course. As students, move through the semester they submit their goal-monitoring sheets. This continuing process helps me provide extra help but also guide them toward necessary resources. It is impressive to see the students’ growth as they reflect on their goals. Below are some examples of student responses.

- “I could use the book’s website more.”

- “One obstacle for me is always time management. I am constantly trying to improve it.”

- “I will monitor my progress by seeing if I do better on the post test on blackboard than the pre test. This will mean that I have learned the material that I need to know.”

- “Well, I have created a calendar since the beginning of class and it has really helped me with keeping up with my assignments.”

- “I feel that I am accomplishing my goals because I am understanding the materials and I feel that I could successfully apply the material in my own classroom.”

- “I know these [Types of assessment, motivation, and the differences between valid and reliable, and behaviorism] because I recalled them multiple times from my memory.

Pressley and his colleagues (Pressely, 1983; Pressely & Harris, 2006; Pressely & Hilden, 2006) emphasize the need for instructors, at all levels, to help students build their repertoire of strategies for learning. By the end of the course, many students feel they now have strategies for learning in any setting. Below are a few excerpts from students’ final submission on their goal monitoring sheets:

- “The most unusual thing about this class has been learning about learning. I am constantly thinking of how I am in these situations that we are studying.”

- “…we were taught new ways to take in work, and new strategies for studying and learning. I feel like these new tips were very useful as I achieved new things this semester.

References

Efklides, A. (2011). Interactions of metacognition with motivation and affect in self-regulated learning: The MASRL model. Educational Psychologist, 46(1), 6-25.

Hellman, C. (1996). Academic self-efficacy: Highlighting the first generation student. Journal of Applied Research in the Community College, 3, 69–75.

Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger, H. L. (2008). The critical importance of retrieval for learning. science, 319(5865), 966-968.

Nelson, T. O. (1996). Consciousness and metacognition. American Psychologist, 51(2), 102-116. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.51.2.102

Nelson, T. O., & Narens, L. ( 1994). Why investigate metacognition?. In J.Metcalfe & A.Shimamura ( Eds.), Metacognition: Knowing about knowing (pp. 1– 25). Cambridge, MA: Bradford Books.

Oettingen, G. (2014). Rethinking Positive Thinking: Inside the New Science of Motivation. New York, NY: Penguin Group.

Pressely, M. (1983). Making meaningful materials easier to learn. In M. Pressely & J.R. Levin (Eds.), Cognitive strategy research: Educational applications. NewYork: Springer-Verlag.

Pressley, M., & Harris, K.R. (2006). Cognitive strategies instruction; From basic research to classroom instruction. In P.A. Alexander & P.H. Winne (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (2nd ed). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Pressley, M., & Hilden, K. (2006). Cognitive strategies. In W. Damon & R. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Roediger III, H. L., & Butler, A. C. (2011). The critical role of retrieval practice in long-term retention. Trends in cognitive sciences, 15(1), 20-27.

Schunk, D. H. (1990). Goal setting and self-efficacy during self-regulated learning. Educational psychologist, 25(1), 71-86.

Tanner, K.D. (2012). Promoting Student Metacognition. CBE-Life Sciences Education, 11(2), 113-120. doi:10.1187/cbe.12