by Dr. Steven Fleisher, CSU Channel Islands, Department of Psychology

Early Foundations

I’ve been thinking lately about my journey through doctoral work, which began with studies in Educational Psychology. I was fortunate to be selected by my Dean, Robert Calfee, Graduate School of Education at University of California Riverside, to administer his national and state grants in standards, assessment, and science and technology education. It was there that I began researching self-regulated learning.

Self-Regulated Learning

Just before starting that work, I had completed a Masters Degree in Marriage and Family Counseling, so I was thrilled to discover the relevance of the self-regulation literature. For example, I found it interesting that self-regulation studies began back in the 1960s examining the development of self-control in children. Back then the framework that evolved for self-regulation involved the interaction of personal, behavioral, and environmental factors. Later research in self-regulation focused on motivation, health, mental health, physical skills, career development, decision-making, and, most notable for our purposes, academic performance and success (Zimmerman, 1990), and became known as self-regulated learning.

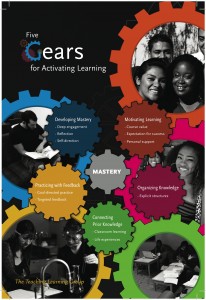

Since the mid-1980s, self-regulated learning researchers have studied the question: How do students progress toward mastery of their own learning? Pintrich (2000) noted that self-regulated learning involved “an active, constructive process whereby learners set goals for their learning and then attempt to monitor, regulate, and control their cognition, motivation, and behavior, guided and constrained by their goals and the contextual features in the environment” (p. 453). Zimmerman (2001) then established that, “Students are self-regulated to the degree that they are metacognitively, motivationally, and behaviorally active participants in their own learning process” (p. 5). Thus, self-regulated learning theorists believe that learning requires students to become proactive and self-engaged in their learning, and that learning does not happen to them, but by them (see also Leamnson, 1999).

Next Steps

And then everything changed for me. My Dean invited Dr. Bruce Alberts, then President of the National Academy of Sciences, to come to our campus and lecture on science and technology education. Naturally, as Calfee’s Graduate Student Researcher, I asked “Bruce” what he recommended for bringing my research in self-regulated learning to the forefront. His recommendation was to study the, then understudied, role and importance of the teacher-student relationship. Though it required changing doctoral programs to accommodate this recommendation, I did it, adding a Doctorate in Clinical Psychology to several years of coursework in Educational Psychology.

Teacher-Student Relationships

Well, enough about me. It turns out that effective teacher-student relationships provide the foundation from which trust and autonomy develop (I am skipping a lengthy discussion of the psychological principles involved). Suffice it to say, where clear structures are in place (i.e., standards) as well as support, social connections, and the space for trust to develop, students have increased opportunities for exploring how their studies are personally meaningful and supportive of their autonomy, thereby taking charge of their learning.

Additionally, when we examine a continuum of extrinsic to intrinsic motivation, we find the same principles involved as with a scale showing minimum to maximum autonomy, bringing us back to self-regulated learning. Pintrich (2000) included the role of motivation in his foundations for self-regulated learning. Specifically, he reported that a goal orientation toward performance arises when students are motivated extrinsically (i.e., focused on ability as compared to others); however, a goal orientation toward mastery occurs when students are motivated more intrinsically (i.e., focused on effort and learning that is meaningful to them).

The above concepts can help us define our roles as teachers. For instance, we are doing our jobs well when we choose and enact instructional strategies that not only communicate clearly our structures and standards but also provide needed instructional support. I know that when I use knowledge surveys, for example, in building a course and for disclosing to my students the direction and depth of our academic journey together, and support them in taking meaningful ownership of the material, I’m helping their development of metacognitive skill and autonomous self-regulated learning. We teachers can help improve our students’ experience of learning. For them, learning in order to get the grades pales in comparison to learning a subject that engages their curiosity, along with investigative and social skills that will last a lifetime.

References

Leamnson, R. (1999). Thinking about teaching and learning: Developing habits of learning with first year college and university students. Sterling, VA: Stylus.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boekaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.) Handbook of self-regulation. San Diego, CA: Academic.

Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulating academic learning and achievement: The emergence of a social cognitive perspective. Educational Psychology Review, 2(2), 173-201.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2001). Theories of self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview and analysis. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.) Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: Theoretical perspectives (2e). New York: Lawrence Erlbaum.