by Roman Taraban, Texas Tech University

“Picky, picky” is a phrase we use to gently chide someone for being overly selective when making an apparently simple choice. However, being picky is not always a bad thing, as I will try to show. Oddly enough, this phrase comes to mind when thinking about thinking about thinking, i.e., thinking about metacognition. To explain the connection, I would like to consider the idea of being picky from two perspectives: research on metacognition and students’ metacognitive behaviors.

My students and I were first attracted to research on metacognition upon reading the work of Michael Pressley and colleagues, which focused on metacognitive strategies for reading comprehension. Noteworthy in those early efforts were projects involving elementary school teachers and classroom interventions geared toward young students in an effort to teach them how to be more metacognitive in their daily schoolwork (Pressley et al., 1995). Other work by Pressley and colleagues analyzed adult metacognitions when reading, using a think-aloud method (e.g., Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995), and metacognitions of experts when reading in their discipline (Wyatt et al., 1993). This research made a lot of sense, as it fit nicely within the broader constructs of active learning and constructivism — the belief that students needed to actively engage materials in order to benefit from study. A simple inference to make is that the application of any active learning strategy will benefit students. That was our assumption when we constructed and tested the Metacognitive Reading Strategies Questionnaire (MRSQ) (Taraban et al., 2000), drawing on the work of Pressley and others. Data from 324 undergraduates from a variety of majors and levels were telling. Of the 35 strategies that we tested, only seven were significantly associated with students’ grade-point averages (GPA). The strategies were Evaluate text for goals, Set goals for reading, Draw on my prior knowledge, Vary reading style based on goals, Search out information for goals, Infer information, and Look for important information (here presented in order of greatest to smallest effect sizes). It was clear that all metacognitive strategies did not predict GPA equally well, and that the successful strategies were mostly related to reading goals. The significant correlations of academic proficiency, measured by GPA, with goal-related reading strategies, are consistent with Garner’s (1987) suggestion that skilled readers know multiple strategies and also know when to apply them.

Recent work on text recall (Schumacher & Taraban, 2014) with an undergraduate sample similar to the earlier study gave us another opportunity to examine students’ strategy use. We asked students to read and study two expository texts and to recall as much as they could either immediately or after a 48-hour delay. After they recalled the information, we asked them to report the strategies they used to learn the information. We organized the specific self-reported strategies into five types, as shown in the table below. A hypothesis that application of any of these strategies would benefit subsequent performance was again not supported. Of the five strategy types, Self-Testing was the only one that was significantly and positively correlated with recall. We might infer that for this sample of readers and the criterion measure, which was recall, the most appropriate strategies were those related to Self-Testing.

|

Key Types of Self-Reported Strategies |

| 1. REPETITION: Re-Reading; Memorize; Repetition |

| 2. FOCUSING ON SPECIFIC ELEMENENTS: Key words; Key concepts; Grouping terms or sentences; Identifying related concepts; Parts that stood out; Parts that were difficult |

| 3. SELF TESTING: Summarizing; Recalling; Quizzing self; Forming acronyms |

| 4. GENERATING COGNITIVE ELABORATIONS: Activating prior knowledge; Recalling related experiences; Re-explaining parts of the text in other ways; Comparing and contrasting ideas; Using analogiesusing mental imagery |

| 5. SEGMENTATION: Grouping sentences for purposes of study; Divide by paragraph |

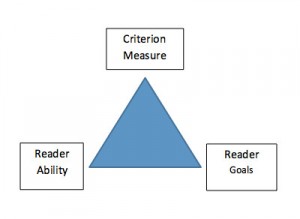

In conclusion, we can draw a few observations. As researchers, as instructors, as students, it is important to be cognizant of three interacting factors when students choose and apply metacognitive reading strategies: the criterion measure, reader-selected goals in light of the criterion measure, and readers’ sense of their own ability as it affects their choices of strategies.

The assumption that the application of any metacognitive strategy will always enhance performance is too simplistic. It does not acknowledge the complexity of strategy choice, and it does not do justice to picky students, who are attempting to choose appropriate strategies for specific circumstances. Some strategies lead to better retention of information and some to better grades. While these will often go together, it might further be the case that picky students know when to employ which strategy. So maybe sometimes it’s good to be picky.

References

Garner, R. (1987). Metacognition and reading comprehension. Norword, NJ: Ablex.

Pressley, M., & Afflerbach, P. (1995). Verbal protocols of reading: The nature of constructively responsive reading. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Pressley, M., Brown, R., El-Dinary, P. B., & Afflerbach, P. (1995). The comprehension instruction that students need: Instruction fostering constructively responsive reading. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 10, 215-224.

Schumacher, J., & Taraban, R. (2014, April). Strategy use complements testing effects in expository text recall. Paper presented at Southwestern Psychological Association (SWPA) Conference. San Antonio, TX.

Taraban, R., Rynearson, K., & Kerr, M. (2000). College students’ academic performance and self-reports of comprehension strategy use. Journal of Reading Psychology, 21, 283-308.

Wyatt, D., Pressley, M., El-Dinary, P., Stein, S., Evans, P., & Brown, R. (1993). Comprehension strategies, worth and credibility monitoring, and evaluations: Cold and hot cognition when experts read professional articles that are important to them. Learning and Individual Differences, 5, 49-72.